New US laws have made a number of projects that were previously unthinkable become profitable, including refuelling Amazon and Walmart forklifts with hydrogen (https://www.economist.com/united-states/2023/04/05/americas-chance-to-become-a-clean-energy-superpower). US businesses believe this will save the country's status as an energy superpower even despite the future restrictions on oil and gas production that will inevitably be imposed on the way to a carbon-free future.

Does the United States have any chance at taking the lead from China in capitalizing on the green transition? And how will the scramble for that lead affect the future of the global economy?

Until the early 2010s, Europe believed that the transition to carbon-free—wind turbines, solar panels and various types of "eco-cars"—would give a quick boost. In reality, it was China that got the boost: Its solar panels quickly displaced those from Europe, it produces more electric cars than the Western world, and it is also the world leader in wind power generation.

As a result, the United States finds itself in an uncomfortable situation: In the traditional energy sector, it is the world leader in oil and gas production and second in coal production. But in the new industries, its prospects are much humbler. To make photovoltaic cells cheaper than in China is unrealistic in purely technical terms—the key costs are labor and electricity for the plants, both of which are cheaper in China and will obviously continue to be so.

Biden's "Navigation Act"?

In 2022, Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act into law—a bill aimed precisely at correcting these problems. It would invest USD 1.1 trillion in clean energy for the future, hundreds of billions of which would be net government investments.

The list of proposed measures is very extensive. For example, Americans will now be able to get tax credits for installing solar panels on their roofs for up to 30 years, USD 30 billion is to be spent on groundbreaking nuclear energy projects, and subsidies for electric cars amount to USD 13 billion.

The crucial point is that the Biden administration's law gives support when it comes to electric cars made in the US from US components. The same goes for solar panels and other things.

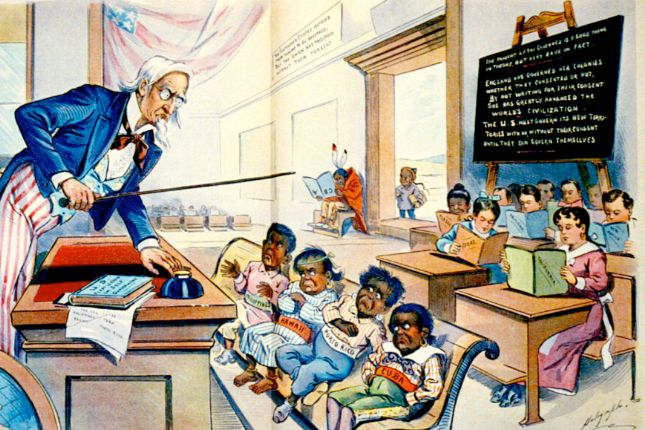

Many observers have compared this to Cromwell's famous Navigation Act of 1651, which remained in force for two centuries. By prohibiting non-English ships from bringing goods into English ports, London dramatically accelerated the development of its merchant fleet and economy as a whole, wresting primacy from the initially richer Holland.

However, there are a number of nuances that significantly distinguish today's situation from that of the 1650s. These are worth elaborating on.

First, the US is not the world's largest potential market in terms of energy. China alone consumes 8.5 trillion of the world's 27.8 trillion kilowatt hours, while the US and the EU together consume 7 trillion.

Approximately 24 trillion kilowatt hours of global electricity physically lie outside the United States. Certainly, the US could protectively close its market of 4 trillion kilowatt hours of annual generation to Chinese companies. But would it make any noticeable difference? After all, the Chinese are already failing to produce the necessary 24 trillion kilowatt hours for the rest of the world.

A Dwindling Slice of the Pie

Protectionism would help US companies cling to 1/6 of the global market, but it would seriously hamper their ability to capture the other 5/6. Other countries are already actively discussing protectionist retaliation against electric cars and other "carbon-free transition" vehicles from the United States.

Ultimately, the capacity of future carbon-free markets would depend largely on the share of these markets in world population and GDP. However, the share of the West in general and the United States in particular is declining both in world GDP and population.

A good illustration of this fact is perhaps the most successful businessman of the green transition: Elon Musk. He started his business in the US, receiving serious subsidies there, and he obtained his original plant in Fremont, California, once owned by Toyota, at a bargain price.

Musk didn't start manufacturing in China until 2020, but he expanded quickly, and Tesla produced 710,000 electric cars there in 2022—52% of its total production. And the vast majority of these automobiles were not exported, but were purchased locally in China.

The nuclear problem

Another serious roadblock on the US's way to achieving the status of an energy superpower of the future is related to the serious problems with nuclear technology, which the Inflation Reduction Act rightly draws a lot of attention to. According to the Act, up to USD 30 billion could be invested in new technologies in this industry—much more than in support of electric cars.

And this is justified because, as a paper in Nature from 2021 demonstrated, in terms of wind turbines and solar panels, "...even in [renewable energy] systems [of the future] which meet >90% of demand, hundreds of hours of unmet demand may occur annually," and that even with the enormous capacity of lithium storage. Wind and solar power plants are geophysically limited by the fact that the sun and wind are intermittent and often unpredictable. It is economically unrealistic to store enough energy in batteries for a two-week freezing anticyclone.

Nuclear power generation is also carbon-free, but unlike wind and solar power, it is quite predictable and independent of the weather. However, the US nuclear industry has significant problems that cannot be solved with money from the Inflation Reduction Act. First of all, it is forbidden in the US to reprocess spent nuclear fuel, so as to avoid plutonium falling into the hands of black arms dealers who could export it abroad.

It seems reasonable, but fast-neutron reactors differ from slow-neutron reactors precisely because they produce more plutonium than they waste uranium-235. If their fuel cannot be reprocessed, then the plutonium cannot be used. That means that the American nuclear industry is doomed to use only uranium-235, of which there is only a 0.7% concentration in natural uranium. Besides, Russia controls a considerable part of the world uranium-235 enrichment market, which means that the US will hardly have access to the steady supply of the fuel they need.

Fast-neutron reactors, which are denied plutonium by US law, can only use fuel with highly enriched uranium (above 15%) instead. However, high enrichment is almost monopolized by Rosatom on the global stage, since it possesses the latest generation of gas centrifuges. So China, for example, gets fuel from Russia for the two 600 megawatt sodium fast reactors (CFR-600) it is currently building.

But in theory, the Chinese can reprocess the spent nuclear fuel from the CFR-600 and get plutonium from it, which would then be used to reload the same reactor. Fortunately, their laws allow such reprocessing. And this means that they will eventually end their fuel dependence on Russia and will solve the problem with the shortage of natural uranium-235. The US, on the other hand, under current laws cannot do so: It is forbidden to extract plutonium from spent fuel.

The bottom line is that the current status of the US as the No. 1 energy power (in oil and gas) is unlikely to persist in a carbon-free future. Locally produced wind turbines and solar panels may serve the local energy industry, but in foreign markets they would be inferior to cheaper Chinese products. It will be similar for electric cars, and the situation for nuclear power is even worse: Under current laws, the United States will hardly be able to provide large nuclear power generation even for the domestic market.