The IMF has predicted that Russia would grow faster than Western countries such as Germany - above 1% of GDP. However, a close look at the figures for the Russian economy reveals something much more unexpected: it looks like Russia's GDP growth in 2023 would exceed 4% and, according to some forecasts, even 6%. What might be the causes and indications of such growth?

Last year, by imposing sanctions against Russia, Western politicians and economists were certain of the imminent collapse of its economy. Bruno Le Maire, the French finance minister, in March 2022 publicly declared that the latest round of sanctions aimed to "cause the collapse of the Russian economy." Swedish economist and former Atlantic Council senior fellow Anders Aslund tweeted that the Western sanctions effectively "took down Russian finances in one day… The situation is likely to become worse than in 1998 because there is no positive end. All Russia's capital markets appear to be wiped out & are unlikely to return with anything less than profound reforms". Respected think tanks were expecting a 15% decline in GDP in Russia.

Nothing could be farther from the reality. Russia's GDP decline in 2022 was 2.1% - much lower than in 2015 (3.0%), after much weaker Western sanctions. Moreover, the IMF now predicts that Russia will grow economically in 2023. It is estimated at a very modest 1.2%, but, as shown below, it will be much higher than 3%.

Why did this happen? This question has been raised many times in the media and the governmental chambers in the West. Why did what seemed to be the G7's main and unbeatable trump card against Russia become a paper tiger in reality?

Terra Incognita

The main problem with Western sanctions on Russia is that no decent Western economist has thoughtfully analyzed the Russian economy. It simply has not aroused their interest. Therefore, judgments about it were like inscriptions on medieval maps: Hic sunt dracones. Many seriously considered Russia a gas station country, dependent on the export of raw materials for its revenues. The thinking of those who imposed sanctions was simple: stop exporting raw materials, and the gas station country would go into recession.

The reality is that for the last decade, raw material exports from Russia (60% of its total exports) have never accounted for more than 18-24% of its GDP. But in the 1990s, the ratio of exports to GDP was as high as 62%. Back then, Russia was a gas station.

And more importantly, when comparing oil and commodity prices with Russia's GDP, it is easy to see no direct correlation. In 1994-1996, oil prices rose by tens of per cent, but Russia's GDP fell. In 2010-2013, oil prices rose by a factor, but non-recoverable economic growth was much lower than in 2000-2008.

From this, we can see: Western observers had little understanding of what was happening in Russia's economy.

Ruble station country

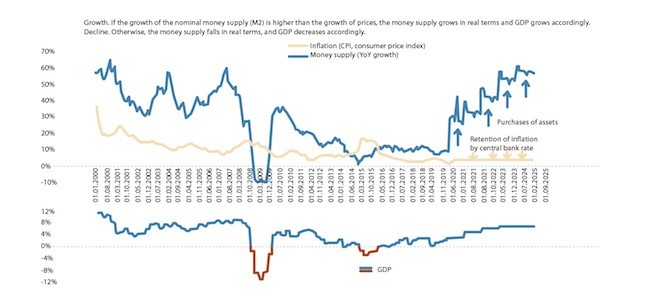

The key driver of economic growth in Russia is the volume of its domestic demand. As is easy to see in the chart below, this domestic demand could grow very rapidly in years of low oil prices (2000-2004) and increase slowly in years of high oil prices (2012-2013). This demand can be seen in the graph of inflation (in red) and the growth of the rouble monetary aggregate M2 (in green). Where the green is much higher than the red (by a factor of 1.2 or more), there is immediately a blue area of GDP growth.

Why does aggregate demand from a major oil exporter show no direct correlation with prices of essential export commodities? The answer is somewhat surprising: Russia practised massive QE in 2000-2008, 2020 and 2022. It is generally believed that the first effective QE took place in the US, and as far as deliberate quantitative easing is concerned, this is the case.

However, as Alexei Kudrin, former Finance Minister in Russia in the 2000s, points out in this interview, in the noughties the Russian macroeconomic authorities were buying up assets - foreign exchange earnings of exporters - en masse on open markets to avoid excessive rouble strengthening and the "Dutch disease" of the economy from such strengthening.

The bulk of the ruble money supply by 2008 was generated by such purchases, which were de facto QE. And on a much larger scale than in the US at the start of the twenty-first century.

After 2008, Russia opted not to engage in such asset purchases, which caused the economy to fall into de facto stagnation - the cumulative GDP growth between 2008 and 2021 was less than what it had been between 2000 and 2008 for a couple of years.

Western sanctions have entirely changed this picture. By depriving the Central Bank of foreign currency reserves, they have sent the Russian authorities searching for "emergency" scenarios to manage the economy. The key lever in this situation turned out to be new quantitative easing. As part of it, the Central Bank printed over a trillion rubles in 2022, and, more importantly, exporters stopped storing their earnings in dollars and euros en masse. Converting them into yuan and rupees was often difficult, making a significant portion of these funds exchanged for roubles.

As Central Bank of Russia governor Elvira Nabiullina has noted, "The process of devaluing bank balance sheets has continued in recent months. There is a change in the structure of demand for money, and instead of foreign currency, roubles are increasingly being used for payments, attracting investment and creating savings.

When exporting customers turned to Russian banks en masse to convert their currency into roubles, they were forced to debit their accounts and credit an equivalent number of roubles to the same customer's account. In macroeconomic terms, the rouble aggregate M2 rose sharply as a result. During the year of fighting in Ukraine, it grew by 23.1%, which dramatically outstripped inflation over the same period. Consequently, the money supply rose with inflation - as did the resulting aggregate demand.

In other words, Russia after 2000 was a ruble station, not a gas station. In the years when the local Central Bank did not conduct QE, its economy stagnated. In the years when the ruble supply grew rapidly, so did GDP.

Forecast for the future

Assuming a ratio of inflation-adjusted ruble M2 growth to Russian GDP growth for 2010-2021, with M2 growing 20% faster than inflation (as currently observed), the Russian economy should grow by 5-6%. In practice, it is far from certain that such values will be achieved in 2023 because economic growth in the current environment must be somewhat hampered by the population's caution about building up their consumer spending. The conflict in Ukraine automatically creates a cautious, wait-and-see attitude among part of the Russian population, in which a growth spree is unlikely.

Nevertheless, even considering these factors, the PMI analysis of the Russian economy in spring 2023 points to rapid growth in both industry and services. Judging by it, GDP growth below 3-4% this year cannot be avoided. If public sentiment changes over the year - under the influence of clear economic growth - growth could also reach 5-6%, i.e. use all possibilities of inflation-adjusted money supply growth.

But could Western sanctions have crushed the Russian economy?

It is clear from the discussion above that to do maximum damage to Moscow, the G7 countries should have avoided at all costs the freezing of their foreign currency reserves and placed restrictions on SWIFT. Under these conditions, the Central Bank of Russia could not introduce retaliatory measures to restrict foreign capital exports. This would have pressured the rouble and forced the Central Bank to quickly spend foreign exchange reserves on maintaining its exchange rate. It was this "reverse QE", the sale of foreign exchange reserves to support the ruble exchange rate, that caused a three per cent (more substantial than 2022) recession in 2015 and the strongest (7.8 per cent) decline in GDP in 2009.

This would have been the most sensible Western plan to damage the Russian economy. However, currently, its implementation is no longer feasible.