On Jan. 9, 1953, The Washington Post published an editorial we can read all these years later as a murmur amid silence. “Choice or Chance” was a blunt worry about what the C.I.A., 5 years old at this time, was getting up to. Was the agency to analyze information it gathered or that had come to it — a matter of chance — or was it actively and covertly to execute interventions of its own choosing?

The agency hardly invented clandestine operations, coups, assassinations, disinformation campaigns, election fixing, bribery in high places, false flags and the like. But it was elaborating and institutionalizing such intrigues, and they were coming to define America’s Cold War conduct.

The Washington Post stood with the objectors — at least it did on page 20 of that winter Friday’s editions. The agency’s activities were “incompatible with a democracy,” Washington’s local paper protested. They risked an unwanted war. Reform was in order. Once again to be noted: The conflict the Post aired concerned method. The Cold War’s taxonomy and Washington’s division of the world into adversarial blocs lay beyond question.

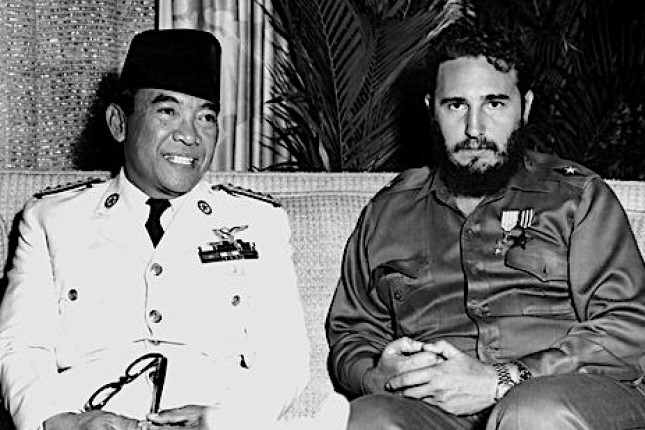

As interesting as the Post’s editorial was the dead quiet that followed. Nothing more was published on the topic. Eight months later, the Post obfuscated the C.I.A.’s role in the coup that toppled the Mossadegh government in Iran; a year after that came the coup that brought down the democratically elected government of Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala, and the C.I.A.’s role in it was once again illegible. Operating with little inhibition, the agency would later plot to plant an exploding cigar in Castro’s humidor and make a pornographic film with a look-alike actor impersonating Sukarno, Indonesia’s too-independent president (later deposed in a C.I.A.–cultivated coup).

American readers and viewers knew next to nothing of all such operations, as intended. Nor did they seem to want to. Citizens were willingly transformed into consumers. A national somnambulance had set in.

Nineteen fifty-three was a peculiar year for the Post to question the C.I.A.’s drift into activist intrigues. Allen Dulles took over as the agency’s director less than a month after the Post editorial appeared.

Dulles put Frank Wisner, a former OSS man, in charge of the agency’s “black operations.” [The Office of Strategic Services was the C.I.A.’s predecessor.] This included making maximum use of the press by compromising its ranks — not least its high command. Journalists were recruited to serve as agents, agents were trained sufficiently to pose as journalists, not infrequently with the blessings of publishers and network presidents. Wisner called his operation “my mighty Wurlitzer” after those turn-of-the-century contraptions that performed musical magic at the strike of a key.

The more alert reporters, correspondents, and editors had long suspected there were C.I.A. operatives in their midst. There was no evidence of this, and, then as now, one did not name a name without any. A silence worthy of a Catholic chapel prevailed for two decades after Wisner set his machine in motion. When this was finally broken, it was as a pebble tossed into a pond produces ever-larger ripples.

Jack Anderson, the iconoclastic columnist, revealed in the autumn of 1973, just as I was crossing the marble floor at The News [the New York Daily News, my first employer], that a Hearst Newspapers reporter had spied on Democratic presidential candidates in the service of the Nixon campaign. At the time Anderson published, Seymour Frieden was a Hearst correspondent in London. Not quite in passing but nearly, Anderson also reported that Frieden tacitly acknowledged working for the C.I.A.

The pebble was tossed. The ripples grew slowly at first.

Colby’s "Limited Hangout"

William Colby, the recently named director of the C.I.A., responded with a standard agency maneuver: When news is going to break against you, disclose the minimum, bury the rest, and maintain control of what we now call “the narrative.” Among the spooks this was and remains known as a “limited hangout.” Colby “leaked” to a Washington Star–News reporter named Oswald Johnston. Johnston’s piece was fronted on Nov. 30, 1973.

“The Central Intelligence Agency,” it began, “has some three dozen American journalists working abroad on its payroll as undercover informants, some of them full-time agents, the Star-News has learned.” Johnston followed this four-square lead just as Colby had wished. “Colby is understood to have ordered the termination of this handful of journalist-agents,” he wrote further down in his report, adding — and this is the truly delightful part — “on the full realization that C.I.A. employment of reporters in a nation which prides itself on an independent press is a subject fraught with controversy.”

Johnston broke a big story, Johnston was a patsy. This was the agency’s “tradecraft” in action.

Once again, the rest of the press let Johnston’s revelations sink without further investigation. But Colby’s gambit was on the way to failing, as was the press’s see-no-evil pose.

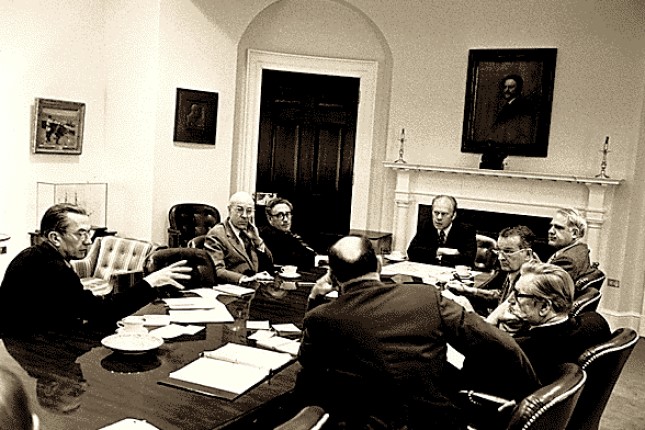

C.I.A. Director William Colby, at left, briefing President Gerald Ford and his senior advisers. Photo: David Hume Kennerly / U.S. National Archives and Records Administration / Public domain.

A year after the Johnston piece appeared, Stuart Loory, a former Los Angeles Times correspondent and then a journalism professor at The Ohio State University, published a piece in the Columbia Journalism Review that stands as the first extensive exploration of relations between the C.I.A. and the press. Another year later, the C.I.A. found itself where it never wanted to be: in the public eye, visible.

Even before it was over, 1975 was known as “the Year of Intelligence.” In January, President Gerald Ford commissioned a committee to investigate the C.I.A.’s illegal breaches. Soon after Ford named his experts, among them none other than Ronald Reagan, the Senate and House convened their own committees to look into the C.I.A.’s doings abroad and at home. The Church Committee, so named for Frank Church, an Idaho Democrat who headed the Senate inquiry, was the committee that mattered. Its final report arrived in six volumes in April 1976, the Year of Intelligence proving a long one.

This was a critical moment for America’s Cold War edifice — or it could have been, I had better put it. The Church Committee was to be the first concerted attempt to exert political control over an agency that had long since, as we say now, “gone rogue.”

In this, Church and his investigative staff held the making of history in their hands. They could have deprived those asserting America’s global hegemony one of their most essential institutions, and they would have decisively cut media’s ties with it. As things turned out, the Church Committee’s failure is wherein the history resides. In the breach, those directing the undertaking elected to obfuscate the obfuscators.

Ties of all sorts to journalists of all sorts were among the programs the C.I.A. was most vigorously determined to keep in the shadows. The agency’s elisions, untruths, and arms-folded refusals to cooperate with Senate investigators must count as a model for all aspiring stonewallers. In due course, the Church Committee found itself drawn into prolonged negotiations with Colby and other senior C.I.A. officials it never should have entered upon.

There were other indicators that failure was on the way. The committee had spent too much time on assassination plots and agency exotica to give the question of press complicity the attention it warranted. Church, who for a time nursed dreams of a run for the presidency, did not want his name on an investigation that would make a faux-patriotic agency protecting national security look as objectionable as it was.

The final “findings” found little to find. No one from the press was called to testify — no correspondents, no editors, none of those at the top of the major dailies or the broadcasters. A year after the committee released its six volumes, Carl Bernstein of Watergate fame elicited in eight words all that needed saying about the 16 months of Capitol Hill drama. Faced with the prospect of forcing the C.I.A. to sever all covert ties with the press, a senator Bernstein did not name remarked, “We just weren’t ready to take that step.”

Bernstein Reveals Press Penetration

It was Bernstein who unwrapped the story. In a 25,000–word piece published in Rolling Stone on October 10, 1977, the ex–Post reporter led readers into a vast universe of connections, co-optation, and collusion. It wasn’t “some three dozen journalists operating as agents.” It was more than 400. All the names were there: the Times, The Post, CBS, ABC, NBC, Newsweek, TIME, the wires.

Those cooperating ran to the top: William Paley (CBS), Arthur Hays and C. L. Sulzberger (the Times), the Alsop brothers (the New York Herald Tribune, later The Washington Post). Arthur Hays Sulzberger, The Times’ publisher, had a signed a secrecy agreement with the C.I.A. and gave his tacit approval to correspondents who wanted to work for the agency.

Seymour Hersh and I. F. Stone, two exemplary independent journalists at this time, had also reported on the C.I.A.’s numerous illegal programs, known in-house as “the family jewels.”

It was Hersh who, in December 1974, broke the story of the agency’s extravagant spying operations focused on antiwar activists and other dissidents — a 7,000–word piece that prefigured the Church Committee by a month and five days. But Bernstein’s mastery of detail on the agency’s penetration of the press — too profuse to recount but briefly — remains nonpareil. Most of it derived from C.I.A. files and interviews with agency offiC.I.A.ls and the journalists the Church Committee never asked to testify.

In what coverage there was of the decades of deceit, the press did its best to convey the impression it was the unscrupulously sullied innocent. Most of those involved professed to know nothing about all the consensual compromises. Some were proudly patriotic. “I’ve done things for them when I thought they were the right thing to do,” Joe Alsop told Bernstein. “I call it doing my duty as a citizen.”

But lapsed memories, lies, and blurred lines were the prevalent responses. While a C.I.A. officer described C. L. Sulzberger as “very eager” to cooperate with the agency, Cy told Bernstein he “would never get caught near the spook business.” Working for the agency and never getting caught working for it seem to have been two different things in Cy’s mind.

The Church Committee left various marks on the record. Some relationships between Langley and the media were broken off as the committee shut up shop. Things were not so openly and incautiously corrupt as they had been pre–Church. This was also the beginning of a long decline in mainstream media’s credibility, which, to be honest, I consider a healthy thing.

The Wurlitzer Plays On

But the Senate investigation stands in hindsight as an early example of that political event we now know too well: It was spectacle. This was how all sides wished it to be. The Wurlitzer’s volume was turned down. But as that anonymous senator said so simply, nobody ever intended to unplug it.

It would be supremely naïve to assume the Wurlitzer does not play in our time, leaving us to live with the Church Committee’s purposeful failing, as we must count it. The agency’s immunity from all oversight is now inviolable. What Capitol Hill committee now would dare to hold hearings such as those that gave the Year of Intelligence its name? Langley’s ties to the press are a closed book. Wikipedia, the alternative encyclopedia with its own objectionable relations with intelligence, as we speak carries this sentence in its entry on the Cold War programs: “By the time the Church Committee Report was completed, all C.I.A. contacts with accredited journalists had been dropped.” This is patently, demonstrably false.

I recount very briefly the evil that supposedly passed. This is the foundation on which many American myths rest. The press and broadcasters still crouch behind this one.

Main photo: Indonesian President Achmed Sukarno and Cuban leader Fidel Castro in 1960, Havana. (Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Source: Consortium News.