The third quarter of 2022 saw US federal budget record a surprisingly large deficit of USD 860 billion. This was the third-largest deficit behind the anti-records of USD 2 trillion in the second quarter of 2020 and USD 1.1 trillion posted in the first quarter of 2021. The trend toward federal budget stabilisation observed in the first half of the year turned out to be unsustainable.

The United States public debt continues to grow at an alarming rate. As of now, it totals USD 30.6 trillion, or 122 per cent of the country's GDP, having more than tripled over the past 15 years!

There have been plenty of attempts to give this phenomenon a plausible explanation ranging from a financial crisis to the COVID-19 pandemic. In reality, however, if one were to look at what has been plaguing the United States over the recent decades from a historian's perspective, it would appear as if America has been waging an undeclared war against an unknown enemy for some forty years...

From Reaganomics to the New American Century

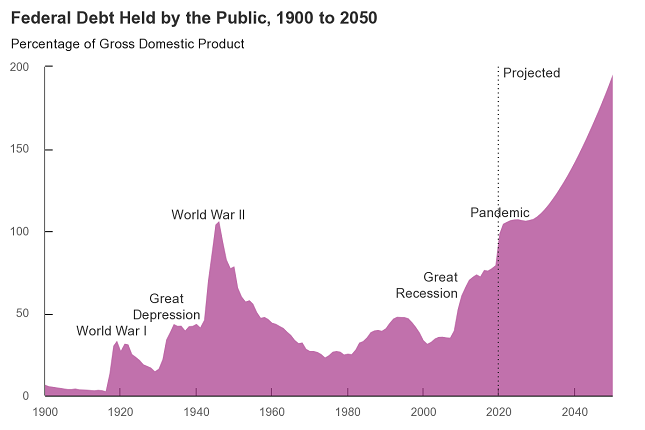

The thought of a protracted and low-intensity war springs to mind when looking at the long graph showing changes in US federal debt as a percentage of GDP over the years spanning 1939 and 2021.

The US federal debt had already soared once before to a level approaching that of today, reaching as much as 199 per cent of the GDP. That was the case from 1942 through 1946.

Back then, amidst the raging World War II, the surge in the budget deficit and debt was precipitous and short-lived, as opposed to the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries when the growth was steady and long-lasting. But, in both cases, this rise was triggered by a common cause of increased military spending.

The debt started to grow again in 1982, with the US escalating its confrontation with the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War. The so-called Reaganomics did produce the desired result: the USSR was forced to acquiesce to the peace deal proposed by the United States and was eventually wiped off the political map of the world altogether.

Graph of US government debt since the beginning of the 20th century.

But what happened next? Over the entire stretch of time between 1982 and 2022, there has been only one period, between 1992 and 2000, of recorded sustained contraction of the US budget deficit and public debt. The Democrats under President Clinton were earnestly trying to bust the country out of the rut dug up by the Cold War's old guard under Reagan. During Clinton's tenure, the budget turned in a surplus of a maximum of 2.3 per cent above the country's GDP in 2000, while the national debt shrank by almost ten percentage points, from 64 per cent to 54.5 per cent of the GDP.

However, with the return of the Republicans to power in 2001, everything went back to the way things had been before. The incursion into Afghanistan, followed by the Iraq invasion, dealt US public finances a devastating blow.

Why did it all happen the way it did?

The Chekhov gun went off

When discussing the root causes of increased US military spending in the 1980s, the Strategic Defense Initiative (the SDI, or the so-called "Star Wars" program) usually comes to mind first. What with fascinating imagery and pretty pictures, this is all quite understandable. In reality, however, the most exciting part was being played elsewhere.

At the heart of the US 1980s, the military programme was a scheme designed to build up a formidable US land force capable of fighting a lengthy war with a comparably-sized enemy force. By then, the Soviets had caught up with the United States in terms of its nuclear capability.

So, for its military planning purposes, Washington had to abandon its concept of a "short war", which assumed that after a brief initial period, in the event of an adverse military outcome, one would have to quickly switch to deploying nuclear weapons. The new challenge called for building a new kind of military. This was the task assigned to, articulated and carried out by then-US Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger.

In his August 1981 speech to the delegates of the Veterans of Foreign Wars convention, Weinberger said that in fulfilling its obligations, the United States "cannot, as it has done in the past, shape its forces and doctrines solely on the assumption that there would be an initial conventional defence with a quick nuclear escalation and thus an early end to the war". Weinberger officially set the course for preparing for a long conventional war in his annual military budget report to Congress in February 1982.

What do the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have to do with any of this, one might ask? Well, even back when this program was only being discussed and approved, some analysts voiced concern that by virtue of the United States building a powerful land army, it would inevitably be forced to use it sooner or later as such are the aftereffects of the US budgetary process.

This is very much in sync with the proverbial Chekhov Gun principle that purports that if you place a gun on the wall in the first act, it will go off by the end of the play.

The gun was built, loaded and hung on the wall in the 1980s.

US troops in Iraq.

It went off in 2003 when the United States invaded Iraq. Iraq's army, one of the world's ten most numerous and fighting-capable militaries of the world, was crushed in a matter of a month and a half.

In 2013, researchers at the Harvard Kennedy School put a number to how much the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had cost the US budget, including medical care and disability compensation as well as benefits for these wars' veterans. This amount was estimated to be between USD 4 trillion and USD 6 trillion.

Full steam ahead to the precipice

The job was done. America was back on the warpath, having chronically destabilised its federal budget along the way. Confronted with enormous military spending, the rescue measures introduced in 2008 and afterwards were starting to look increasingly desperate.

In a sense, the 2008 economic crisis itself was a product of fiscal distortions. Shifting public finances toward meeting the needs of war called for more monetary incentives and more relaxed regulation…

The anti-COVID financial measures dealt the final blow. Above all, these additional injections of capital were needed to prop up the exaggerated stock prices and ballooning derivatives market.

Today, the US money market is ailing. The rates of turnover in the M1 and M2 money supply aggregates, known as money velocity, have all but become equal to each other and barely exceed the ratio of 1. This means that there's basically no money multiplier in the US economy any more. The Federal Reserve is directly micromanaging the entire US financial system along with the government debt market.

Notwithstanding this state of play with the US public finances, the United States has effectively become involved in fighting a proxy war against Russia in Ukraine and is preparing for an escalation of its military and strategic confrontation with China.

Is the US economy ready for another round of the bizarre war America has been fighting for the last forty years?

Granted, the US economy continues to be the world's most powerful and advanced economy. Moreover, with Europe spinning into the abyss of de-industrialisation as a result of the ongoing energy crisis and disruption of its economic ties with Russia, the US is being presented with new opportunities for strengthening its economic primacy. These could be seized by either moving European manufacturing facilities to the US or encouraging a new wave of immigration of Europe's highly qualified workforce.

But will it help address the problem of the budget deficit and growing federal debt? Most likely not, as things have already gone too far. Surely, the US could continue printing cash in nearly any quantity without having to fear immediate consequences. The US dollar and US government bonds simply have no viable alternatives. But this cannot go on forever. If the last fifteen years are any indication, a decline of state finances can occur very quickly, even if your starting position seemed to be nearly perfect.

The assumption that fomenting instability in the outside world, along the lines of how it was done during World War I and World War II, could produce the same results may not work the third time around. After all, the US will have to face Russia and China's bloc. And it will have to walk into this confrontation, having already been worn out by its "bizarre forty-years' war".

***

For reference:

Budget deficit as percent of GDP

Federal debt as percent of GDP

Federal debt in monetary terms

Money velocity