From July 28 to August 5, 1973, 8 million people, including 25,600 guests from 140 countries, participated in the 10th World Festival of Youth and Students in East Berlin (German Democratic Republic or DDR).

The festival was a key activity organised by the World Federation of Democratic Youth (WFDY), formed at the World Youth Conference in London in November 1945.

The 1973 festival marked an epochal moment: the Vietnamese appeared to be on the march against U.S. forces while, from Mozambique to Cabo Verde, the peoples of Portugal’s African colonies were preparing to seize power, and in Chile the Popular Unity government was in a major struggle against copper multinationals and Washington.

As multiple possibilities unfolded, young people felt that they had a genuine future. Many of the festival’s participants had been radicalised during the campaign to free communist Black Panther Angela Davis from prison, and then there she was on the stage in East Berlin, standing beside the Soviet cosmonaut and first woman in space Valentina Tereshkova.

The young attendees heard music from over 100 groups and soloists from 45 countries, including South Africa’s Miriam Makeba and the Chilean band Inti-Illimani, who sang:

We will prevail, we will prevail.

A thousand chains we’ll have to break.

We will prevail, we will prevail,

We know how to overcome misery (or fascism).

Peasants, soldiers, miners,

The women of our country, too,

Students and workers, white-collar and blue,

We will carry out our duty.

We will sow the land with glory.

Socialism will be the future.

All together, we will make history

To prevail, to prevail, to prevail.

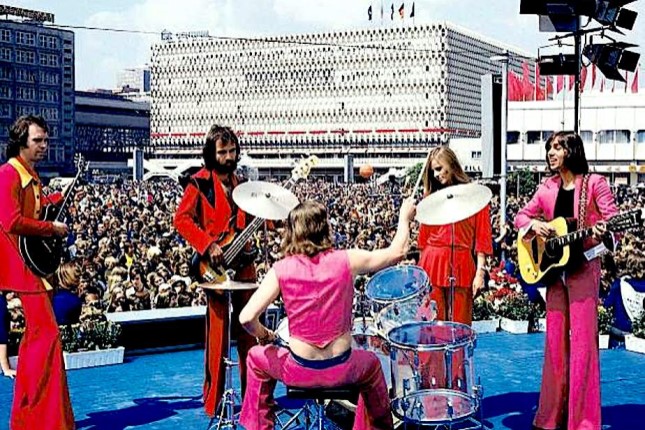

10th World Youth Festival opening celebration on the East Berlin boulevard Karl-Marx-Allee. Photo: Bild und Heimat.

Ours is such a different time. Of the 1.21 billion youth (between ages 15–24) across the world – which account for about 15.5 percent of the global population – seven out of 10 “are economically disengaged or under-engaged,” according to a recent World Bank study.

Those who are disengaged are “not in education, employment or training,” also known as NEETs. In 2021, across the world, roughly 448 million youth were estimated to be disengaged or under-engaged — a horrifying figure.

In Latin America, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa, rates of disengagement or under-engagement have surpassed 70 to 80 percent. Overall, youth comprise 40 percent of the world’s unemployed population.

Certainly, these facts weigh heavily on young people: amongst 10-to-19-year olds, 1-in-7 experience mental health troubles, with suicide the fourth leading cause of death among adolescents between 15 and 19 years old.

In Algeria, there is a word to describe these young people: hittis, which means “walls” and refers to young people leaning against walls.

The feelings of great joy and hope that permeated East Berlin in 1973 simply do not exist amongst most of the world’s youth today.

Those who are politically charged up are demoralised by the failure of the Great Powers to act speedily to address the climate catastrophe. Others find themselves sucked into the vortex of social media, where algorithms are designed to create a kind of apolitical politics, often one of malice and anger rather than struggle and hope.

Of course, there are pockets of enthusiasm, struggles led by young people on the fronts of redistribution and recognition, on picket lines and in marches, raising their own banners that echo the slogans of the youth of 1973.

They are interrupted by the banalities of neoliberalism and offered false solutions such as those reflected in the pieties of the titles of the United Nations’ flagship World Youth Reports “Youth Social Entrepreneurship” and “Youth Civic Engagement.”

Nonetheless, the youth slogans in motion are richer and fuller than the solutions offered to them, marked by an understanding that a disengagement rate of over 70 percent will not be fixed by skills training or social entrepreneurship.

The band WIR performs at Alexanderplatz during the 10th World Festival. Photo: Imago / Gueffroy.

This week, we are looking back at the 1973 World Festival to revive our sense of the possibilities still available for young people, the desire for something far more enticing than the barrenness of capitalist solutions.

Our colleagues at the International Research Centre DDR (IFDDR), based in Berlin, are commemorating the 1973 World Festival with a campaign from July 28 to August 5 on the festival’s impact on different countries, from Vietnam to Cuba, from Guinea-Bissau to the U.S. and Chile (you can track the series on IFDDR’s social media channels).

A month after the 1973 festival ended, a section of the Chilean military, led by General Augusto Pinochet, left their barracks, attacked the Popular Unity government of President Salvador Allende (who died in the melee), and began repressing all left forces in the country.

In September, on the 50th anniversary of the coup, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research alongside Chile’s Instituto de Ciencias Alejandro Lipschutz Centro de Pensamiento e Investigacion Social y Politica (ICAL) will publish dossier No. 68, “The Coup Against the Third World: Chile, 1973.”

The dossier will provide more context for that coup and its global impact, which was foreshadowed by the tone of the 1973 youth festival, described in an article written by IFDDR that is embedded in the rest of this week’s newsletter.

Chileans at the 1973 Festival. Photo: Jürgen Sindermann via Bundesarchiv Bild 183-M0804-0760.

In 1970, Popular Unity, a coalition of left-wing forces, won the elections in Chile, and Allende became president. The euphoria over this victory reverberated in other socialist states, even though the situation on the ground remained tense.

The fact that the resource-rich country wanted to take an independent path and have sovereignty over its extractive industries – which had been dominated by U.S. and European companies for decades – was not accepted by the West.

Allende’s measures, such as the nationalisation of the mining sector, provoked those who stood to lose the most: the old Chilean elites, large landowners, foreign corporations and their governments.

From the beginning, this reactionary threat hung over the progressive alliance like a dark shadow. Attacks and assassinations of representatives of the Popular front were not uncommon.

In view of the fragile situation in her homeland, Gladys Marín, then general secretary of the Chilean Communist Youth, emphasised in an interview: “The Solidarity Meeting for Chile here in Berlin had a significant international weight because it took place at a very critical time for my homeland.”

She led the 60-strong Chilean delegation, which was made up of a cross-section of the organisations represented in the coalition government, to the 10th World Festival in the DDR. Chile was one of the defining themes of the festival, where solidarity with Popular Unity as it faced an ongoing imperialist offensive resounded again and again and “Venceremos” reverberated through the crowd.

But the certainty of victory experienced a bitter setback. Shortly after her return from an extended trip as a representative of the new government that stretched as far as Asia, Marín was forced into hiding after Pinochet’s coup on Sept. 11, 1973.

In West Germany the coup was met with joy, and trade with the Pinochet dictatorship subsequently boomed. In 1974, exports from West Germany to Chile increased by over 40 percent and imports by 65 percent.

Franz Josef Strauss, long-time West German politician and chairman of the Christian Social Union (CSU), commented cynically on the coup at the time: “In view of the chaos that had reigned in Chile, the idea of ‘order’ suddenly sounds sweet for the Chileans again.”

Marín, now in exile, repeated her journeys to fraternal countries. This path led her through the DDR again, among other places that offered refuge to exiled Chileans such as Michelle Bachelet (who later became president of Chile in 2006).

The events in Chile deepened the solidarity movement in the DDR. Immediately after the coup, people gathered spontaneously on the streets of Berlin and expressed their support for Popular Unity.

The Solidarity Committee of the DDR set up the Chile Centre in Berlin, which coordinated fundraising and aid for almost 2,000 Chilean immigrants. International solidarity campaigns were launched, including one devoted to the release of Luis Corvalán, the general secretary of the Communist Party of Chile.

The Chilean delegation’s visit to the World Festival earlier that year had consolidated the solidarity movement, which would prove key in the years following the 1973 coup.

As Marín told the enthusiastic youth who received her at the festival: “We have come to Berlin with great expectations… The festival will further strengthen our common worldwide struggle against imperialism.”

Inti-Illimani with Gladys Marin at the 10th World Festival of Youth and Students. Photo: Courtesy of Jorge Coulon.

Jorge Coulon, one of the founders of Inti-Illimani who travelled from Santiago to sing at the festival in Berlin, told me: “We were part of a very large delegation of union leaders, artists, workers, social organisations, journalists, and students. … A few months earlier, Salvador Allende had defined Chile as a silent Vietnam due to the underhanded nature of the Nixon administration’s attack on the foundations of the Chilean economy and its financing of forces interested in overthrowing the Popular Unity government. With the spirit of resistance, enveloped in the magnificent solidarity of the world’s youth [at the festival], we sang the hymn of Popular Unity at the inauguration, and the conscious and solidary world chanted the refrain with us: ‘Venceremos, a thousand chains we’ll have to be break.’ ”

Main photo: Angela Davis with DDR Minister of Education Margot Honecker and Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, East Berlin, 1973 © ADN-Bildarchiv.

Source: Consortium News.