Given the alarming signs of a looming banking crisis, a dramatic reduction in economic growth—with continued high inflation—would seem to be inevitable. The World Bank is predicting an entire lost decade in this regard.

However, a careful analysis of the global economy indicates a rather different possibility: a divergent development. Until 2030, a smaller proportion of the world's economies may indeed slow down, but others may soon do the opposite. Who will be the winner and who will be the loser in the global economic race?

In the Western media, the general assessment of the global economic situation is fairly unanimous: everything is heading towards deterioration.

Liliana Rojas-Suarez, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, proclaimed: "You don't have any real motor of growth. It's not that it's one region that is weaker than the other. Wherever you look, growth is really low, and so of course that affects everything else."

The reasons are clear: the US and the EU are sharply tightening the money supply (in the United States, its decline has been the fastest since the 1940s), but this has not helped to stop core inflation yet. Consequently, Western central banks will maintain tight monetary policies, and as Friedman noted, this inevitably means worsened prospects for economic growth.

David Malpass, the outgoing head of the World Bank, even ventured to say that the world economy is suffering from stagflation—low GDP growth with high inflation. But is this really the case?

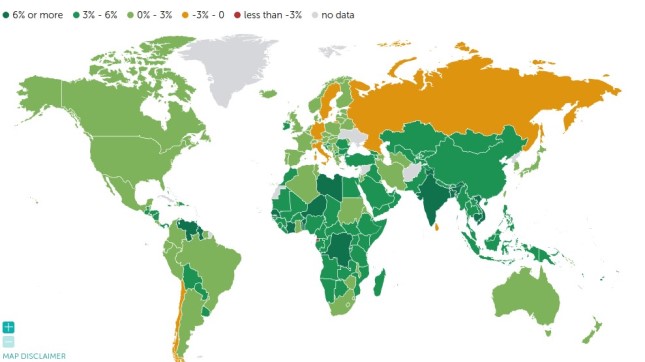

However, just a glance at the economic map of the world from last year is enough to cast doubt on this. Not a single major country experienced a decline of even 2.5% of GDP—including Russia, which a year ago was promised -10% or worse. China, the world's first PPP economy, grew by more than 4%; the US, the second economy, by about 1%; India, the third economy, by more than 6%. Meanwhile, energy prices and inflation were clearly higher in 2022 than they will be in 2023. That is, there are even fewer objective preconditions for a downturn now than before.

To understand which decade was truly lost, it is worth looking at objective figures. For example, between 2010 and 2020, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, global per capita GDP grew by 12.75%. In 2000-2010, growth was much higher—18.7%; in 1990-2000—16.0%; in 1980-1990—14.76%, and in 1970-1980—20.7%.

From this it is easy to see that the lost decade in the global economy is already behind us—the 2010s.

Meanwhile, the growth rate of per capita GDP in 2022 (3.1% GDP growth with only 0.83% population growth) was much higher than that of the 2010s.

If the world could continue to grow at the pace of 2022, the 2020s would see economic growth as fast as the 1970s, and would far surpass any decade between 1980 and 2020. We cannot write off the high performance of 2022 to restorative post-consolidation growth, as global GDP already exceeded pre-consolidation levels in 2021.

Thus, we are faced with something bizarre. The World Bank and Western politicians talk about a lost decade, but so far we are seeing a decade of impressive growth. Why is the rhetoric of politicians and economists so much more alarming than the raw data?

Financial, Demographic, and Investment Concerns

As the World Bank notes, experience has shown that financial crises in the developed world lead to recessions on a global scale and can permanently slow growth for the planet as a whole.

This is certainly a weighty thesis, but recall that there was a global financial crisis and recession in the 2000s (2008), and not in the 2010s; and yet, even with COVID-19 in the 2010s, per capita GDP growth was the same.

There's another equally important point from the World Bank report: demographics. It notes, quite correctly, that the global fertility slowdown is at a frightening pace, and is already affecting the amount of available labor and demand growth. This is true, but it is important to realize that this only threatens the global absolute GDP growth as a whole. Per capita GDP does not suffer when the birth rate slows down.

Other concerns from the WB report seem more reasonable: middle- and low-income countries continue to grow faster than rich countries, but they are only closing the gap between them at a rate of ~2%—that is, at a lower rate than in the 2000s (when it was over 3% per year).

For all the validity of the Bank's concerns, it should be noted that China has been the main contributor to the particularly rapid narrowing of the gap between rich and poor countries over the past 20 years. China's development is now slowing, and it could not be otherwise: it has become a middle-income country, and they normally grow slower than low-income countries.

A really serious concern in the WB report could be the declining rate of investment growth. However, if we isolate the role of China in this decline, it turns out that the slowdown in investment growth there has also led to a global slowdown in investment growth.

The New Normal

Overall, the World Bank's fears seem to stem from it "missing" the ending of the low base effect. The developing world of the 2000s and earlier was rapidly narrowing the gap with rich countries because it was much poorer than it is now. China, for example, doubled its per capita GDP in the 2000s, but unsurprisingly, it failed to do so again in the 2010s, growing only one and a half times. This slowdown could not but happen: Middle-income countries, like the China of the 2010s, do not grow like low-income countries, like the China of the early 2000s.

More intriguingly, the World Bank's concerns are shared by finance ministers and politicians from the US and Europe. Their position looks more reasonable: Today the global energy price index is at a much higher level than it historically has been, and the recent OPEC production cuts have people worried that energy will continue to be significantly more expensive than normal.

Under such conditions, the US Fed or the ECB cannot cut rates, which means that the money supply in the EU and the States would continue to shrink, which certainly promises a recession there this year and next.

At the same time, it should be understood that the situation is far from being as perilous for the Third World as a whole as it is for the Western World. India and China have energy systems based on their own coal. They import oil from Russia cheaper now than do Western countries (due to sanctions, they cannot buy Russian oil directly, like the Chinese or Indians). Therefore, the impact of the ongoing energy shock on non-Western countries is unlikely to be significant.

This is also seen in the forecasts voiced by the head of the OECD, who expects GDP growth of 2.2% in 2023 and 2.7% in 2024. Given that the lowest rates in this period are expected precisely for Western countries, others are likely to show fairly decent numbers.

Moreover, even a recession in the West—likely if the Fed and the ECB continue their tight monetary policy from last year—is unlikely to have too negative an impact on GDP in the developing world. The fact is that over the past 20 years China (but not only China) has shifted from an export-led growth model in the US and the EU to a domestic demand growth model. This is clearly visible in the declining share of exports in its GDP and, in particular, in the declining ratio of its balance of payments surplus to GDP. Similar trends are observed in India.

Consequently, the world's largest developing economies are becoming less and less dependent on the West. This means that fears of a "lost decade" appear reasonable only in relation to Western countries at the moment.

Under such conditions, the US Fed or the ECB cannot cut rates, which means that the money supply in the EU and the States would continue to shrink, which certainly promises a recession there this year and next.

At the same time, it should be understood that the situation is far from being as perilous for the Third World as a whole as it is for the Western World. India and China have energy systems based on their own coal. They import oil from Russia cheaper now than do Western countries (due to sanctions, they cannot buy Russian oil directly, like the Chinese or Indians). Therefore, the impact of the ongoing energy shock on non-Western countries is unlikely to be significant.

This is also seen in the forecasts voiced by the head of the OECD, who expects GDP growth of 2.2% in 2023 and 2.7% in 2024. Given that the lowest rates in this period are expected precisely for Western countries, others are likely to show fairly decent numbers.

Moreover, even a recession in the West—likely if the Fed and the ECB continue their tight monetary policy from last year—is unlikely to have too negative an impact on GDP in the developing world. The fact is that over the past 20 years China (but not only China) has shifted from an export-led growth model in the US and the EU to a domestic demand growth model. This is clearly visible in the declining share of exports in its GDP and, in particular, in the declining ratio of its balance of payments surplus to GDP. Similar trends are observed in India.

Consequently, the world's largest developing economies are becoming less and less dependent on the West. This means that fears of a "lost decade" appear reasonable only in relation to Western countries at the moment.