The cyclical struggle to raise the United States' debt ceiling regularly gives rise to talk of the "trillion-dollar coin" project. But for all the exoticism of the idea, it raises rather ordinary questions. Is it really impossible to do without it? Contrary to many Western conspiracy theorists' opinion that the US debt is completely insurmountable under present economic conditions, the problem is actually somewhat exaggerated and will remain as is for decades to come.

Why, and what does this portend for the world at large?

The crux of the problem

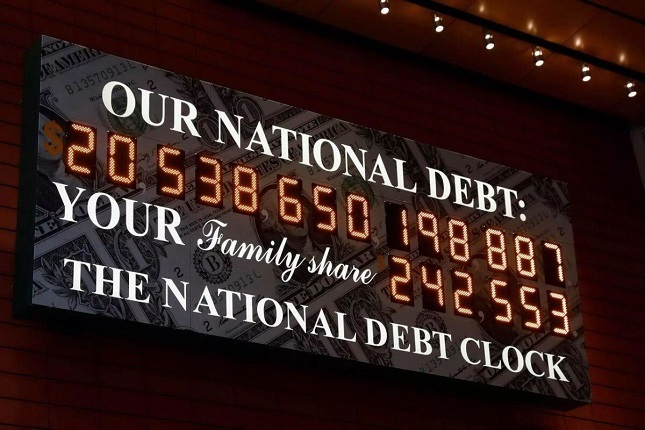

America has not had to make large interest payments on its huge national debt (already in excess of USD 31 trillion) for years now, thanks to the low-interest-rate policy it has pursued since 2008.

What changed was the Fed's fight against inflation last year, for which it raised rates so severely that interest payments on the US debt will exceed a trillion dollars a year for the first time in history this year.

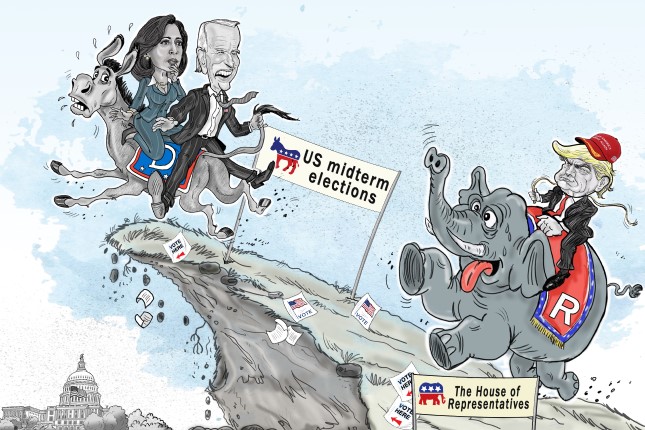

This further intensifies the debate in Congress whenever the debt ceiling is raised. Democrats have to make concessions to get Republicans to approve the ceiling increase, which only delays the whole process, leading to periodic government shutdowns.

As partisan strife has grown considerably in recent years, many fear a permanent stalemate: Republicans might at some point refuse to raise the ceiling, causing a temporary government paralysis.

This has re-popularised the long-promoted "trillion-dollar coin" idea. The thing is that the US has a legal loophole: Platinum coins are poorly regulated by local laws, and formally, the state, represented by the Treasury, can assign them any denomination regardless of physical weight and without the approval of Congress. By contrast, the rest of the instruments of payment are strictly regulated by law and cannot be issued without Congressional approval.

By issuing such coins, the Treasury could formally "pay off" the debt by the trillions, despite the fact that the given value of such coins would exist only on paper (no one would pay an amount equal to the GDP of a large country for a small piece of platinum).

It would be impossible to challenge such a move on purely legal grounds. But psychologically, many in the business world consider the idea to be fraud, or foul play. It could be possible only if there is no other foreseeable solution to the problem.

The only way out?

However, whether there really is no other way out is an open question. The fact is that Congress traditionally has rather intense discussions about the national debt—the issue is politicised, and rarely undergoes objective review.

If you start with the figures, the US' national debt is, to put it mildly, actually not so extraordinary. It is currently about equal to the GDP (even slightly less, according to government figures).

Meanwhile, this figure is higher even in France, but there are no public discussions about it there. Likewise, there are no clashes in parliament and no government shutdowns while a new ceiling is being worked out. In fact, France, like most countries in the world, does not have such a ceiling.

In Italy, the net national debt is above 130% of the GDP, but they also are not discussing it.

Japan's formal public debt is about 270% of its GDP. True, part of it is actually owned by government agencies, but even so, the debt not bought back by the government is still 170% of GDP. Per capita public debt in the US is not only lower than in Japan, but also lower than in Singapore.

Finally, all of it is denominated in the national currency. That is, at any time, the Fed could issue any number of dollars to buy up some of the national debt. It has already made such large purchases in times of crisis. So what is the problem?

If we turn to the history of Western finance, the question becomes even more acute. In the 19th century, England had a national debt of more than 200% of its GDP, while simultaneously reaching the peak of its political, industrial, commercial, and financial power − and this at a time when it could only pay its debts in gold-backed pounds, which could not be printed as the Federal Reserve can do with the dollar today.

But when Britain reduced its public debt to less than 50% of its GDP, its role in the world economy began to diminish in profound ways. Is high debt really a major problem? And why is China accumulating government and public corporation debt at a rate not much different from that of the United States?

All of this shows that the "trillion-dollar coin" problem needs to be viewed from a different perspective. Extraordinary measures are only needed in extraordinary circumstances. But there are no such circumstances: A US default on its national debt is impossible because the debt is dollar-denominated. And in any case, the debt is not so large by modern (see Japan) or historical standards (see Britain).

Less publicity, more peace of mind

The debt ceiling is not so much an economic problem as a political one. The crisis emerged in 2011, at a time when the Democrats' and Republicans' ability to engage in political dialogue was beginning to decline, and any excuse to criticise the other party, including the growth of the national debt, became a matter for excessive exploitation.

A more rational solution to the issue of the national debt would be to avoid politicising and using it as an argument in inter-party struggles. A tacit agreement between the Republican and Democratic parties where each party automatically votes to raise the national debt when the other party is in power could have closed the issue.

Conversely, using a trillion-dollar coin would be a violation of the spirit of the separation of powers. If Congress can put the brakes on the national debt build-up, why can't it be prohibited from printing trillion-dollar coins? A government that has to exploit holes in its own laws to pay its civil servants' salaries on time is a far more unnerving picture for society and investors than even a government that regularly puts on a show about breaking through another debt ceiling.

All the more so when, judging by both history and modern times, the ceiling was initially set too low.