On January 17, Greta Thunberg was detained by German police at a protest against low-quality coal mining in the already completely abandoned town of Lützerath in the so-called Land of Coal − North Rhine-Westphalia.

The notorious eco-activist superstar has been out of the public eye recently, and her appearance in front of the cameras accompanied by German policemen proved to be a timely, and well-orchestrated, boost to her publicity.

To be sure, it's a huge step back from the path of new green technology, but with the gas squeeze, the coal resurgence is the harsh reality of today's Germany, driven by the acute need for fuel already this winter.

The coal mining is handled by RWE AG, the leading German energy company, headquartered in Essen. The company has already faced considerable media criticism, and clashes with activists have become commonplace, as anti-coal activists have been fighting for nearly 10 years now to save Hambach Forest from being cut down.

To extract the coal, RWE is planning to demolish the houses in the hamlet of Lützerath on the edge of the Garzweiler open-pit mine. Everything is settled and the locals have already left the village, with compensation from the company.

On the company's official website, they explain the Lützerath project as a lesser evil to avoid the destruction of the other localities surrounding Garzweiler and overcome the current crisis, building a bridge to the bright future of Germany's dreams, without the coal and nuclear industries.

The destruction of Lützerath is also attributed to the war in Ukraine. Trying hard to convince the public, RWE resorts to complete nonsense, claiming that, "in the current energy crisis, ensuring security of supply is vital. At the same time, protecting the climate remains one of the key challenges of our time. RWE supports both."

This is a rather absurd statement, a lie drawing the ire of eco-activists who fight this ultimately self-seeking concern of the energy company. The negative effects of coal mining are well known, and it is calculated that burning lignite − a particular type of coal that lies under the streets of Lützerath − produces over 1,000 grams of CO2 emissions per kilowatt-hour. For comparison, nuclear plants produce only 117 grams of CO2 emissions per kilowatt-hour. But still, the ecologically-minded Germany prefers coal.

For its closest neighbour, France, which operates 56 nuclear power plants, it seems to be a matter of culture: Germany is traditionally an anti-nuclear country, especially after the Chernobyl (1986) and Fukushima (2011) disasters. Only three nuclear power plants remain in Germany now, and before the Russia-Ukraine military conflict, there were plans to shut them down completely, though German Chancellor Olaf Scholz decided in the fall that all three plants should run at least until this coming April.

Of course, that is not enough to supply the entire country. Nuclear power currently covers only 6% of the needed electricity, though it was at 30% before the other plants were closed. With the breakdown of its partnership with Russia and the shortage of game-changing gas, Germany has found no better option than to dig coal.

Thus, eco-activists and previously affected locals from neighbouring villages have moved into the abandoned Lützerath homes to block RWE's progress. In theirs and Thunberg's opinion, the company's coal mining undermines the German government's official plans to switch to ecological technology by 2030 and will cause irreparable damage to the environment.

Police began dispersing the unpeaceful protestors, who were even throwing Molotov cocktails, on January 11.

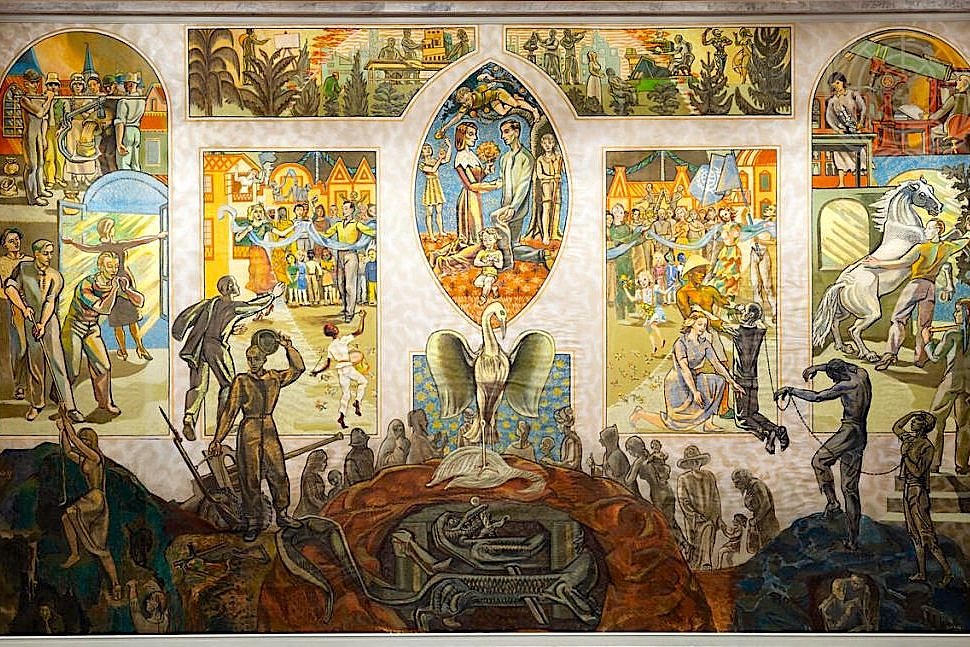

Such an acute reaction is no coincidence, with the eco-activists' rage fueled by the more than forty years of protests by locals. Houses being demolished, old villages being devastated, and locals being relocated due to RWE's expansion of the quarry is nothing new.

Even historical monuments (there are about 33 in the area), churches built by the locals, old farms, and still-livable houses (some with 600 years of history) are all being erased. "And all this just to completely shut down the coal industry by 2038?" the locals ask. Germany has passed a law to completely phase out coal by 2038, but seems to have no real intention of giving it up.

And Lützerath is far from the first town in this row. Locals sharply criticize the company, saying the compensation will not be enough to build new houses of the same size and that the infrastructure of the new villages isn't well thought-out − there will not be any kindergartens, schools, etc. But the worst thing for them is that they will never be able to return home again − only to a huge hole where their homes once stood.

However, eco-activists think more broadly: It's not only the story of a single village that concerns them, but also the global climate change caused by coal mining and use, which destroys the atmosphere and devastates many rare animal species and human habitats. Greta Thunberg expressed her opinion on this matter in an earlier interview: It is "a bad idea."

Clearly, Thunberg and other eco-activists are criticizing the EU member nation's contradictory decisions: On the one hand, Germany assures that it will abandon coal by 2038, but on the other it promotes the revival of the coal industry, and is willing to sacrifice entire settlements to do so.

While this crisis is supposed to be due to the war in Ukraine, it is fair to say that a considerable role is played by the EU itself, as it actively sponsors the Ukrainian confrontation with Russia, which only aggravates both the military conflict and the energy crisis.

Obviously, we are in a very tense situation, and the concessions that EU countries are forced to make are unleashing all kinds of internal conflicts. Those who support the coal industry are trying to convince themselves and others that this is a temporary solution − a bridge to be crossed in times of crisis. But are the pillars of this bridge strong enough to withstand the onslaught of internal strife?