Inevitable aggravation of the energy crisis will affect not only European consumers this winter - it will ricochet many countries far beyond the borders of Europe. Among the first is Japan. At the same time, the inverse relationship also remains: the demand for energy resources in Japan and, in general, in Northeast Asia directly affects the supply of LNG (the main substitute for Russian pipeline gas) to the European market.

By analogy with Europe, energy risks for Japan are divided into two main groups: the occurrence of a physical shortage of gas and electricity and a sharp increase in energy costs due to high world energy prices (in addition to LNG, these are primarily oil and petroleum products).

Shortage risks

On September 20, the Japan Meteorological Agency released an alarming forecast for the coming winter, according to which average air temperatures in the most densely populated areas of the country are expected to be below multi-year norms, which means potentially higher demand for LNG and steam coal. At the same time, unlike European countries, Japan has so far hardly taken steps to artificially limit gas demand.

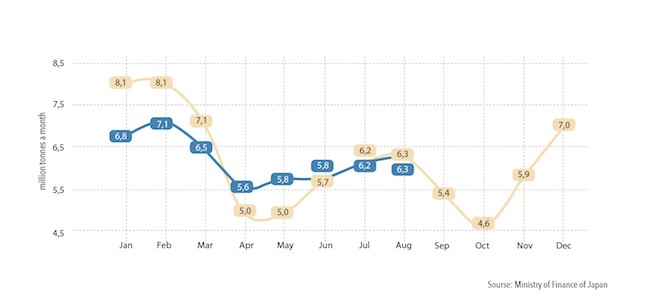

Instead, Japanese electric power companies actively replenished their LNG reserves in the summer, which significantly exceeds the average values for 2017-2021. Moreover, even foreign storage facilities have been used for these purposes. For example, Kyushu Electric Power Co. leased storage facilities from Pertamina in Indonesia.

Stockpiling despite high prices reflects the risks of reduced LNG supply in the winter. In addition to uncertainty about the stability of Russian supplies (due to political reasons), any force majeure event causes considerable concern. In recent weeks, this is primarily the decision of the Malaysian company Petroliam Nasional Bhd. reduce LNG supplies to Japan until the end of 2022 due to the accident on the Sabah-Sarawak gas pipeline that occurred on September 21. As a result, the total export of Malaysian LNG to Japan in October-December will decrease by at least 20%. But the main risk of supply cuts comes from price competition with European consumers. At the end of 2021, Japan lost its decades-old status of the market with the so-called premium gas pricing model. In terms of stock exchange prices, Japan is now steadily losing to Northwestern Europe, and apparently, this trend will continue into the winter period. Or Japanese companies will have to inflate purchase prices to outbid European buyers.

LNG demand itself has entered in Japan what appears to be a period of progressive, albeit slow, decline. The main driver of this process will be the partial resumption of nuclear generation. However, the expected reduction in demand will mainly take place after 2024. In the meantime, against the backdrop of declining consumption in China, Japan in 2022 regained its status as the world's largest LNG importer. In January-August 2022, it imported 50.1 million tonnes of LNG, which is only 1.2 million tonnes less compared to 2021 (-2.3% YoY). It is likely that in September-December 2022, LNG imports will also be close to the values of 2021, and the total annual supply may remain at the level of 72-74 million tonnes.

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan has developed a set of measures in case of a shortage of gas supply, which includes:

- introduction of incentives to limit gas consumption by households, small and medium-sized businesses;

- restrictions or even a complete ban on the use of gas by large industrial consumers;

- empowering the state-owned company JOGMEC to purchase LNG in case of unforeseen circumstances if private gas companies are unable to make purchases on their own;

- launching a gas exchange mechanism (redistribution of reserves) between energy companies.

Power industry problems

Due to the sharp rise in energy prices and extreme heat, Japan in the summer of 2022 faced a physical electricity shortage for the first time since 2015, forcing the government to urge the population to save electricity for a three-month period. The occurrence of a shortage of electricity is also possible in winter, given the low forecast indicators of the reserve capacity. Tokyo agglomeration already faced the risk of electricity rationing in March 2022, when the spring cold snap coincided with a strong earthquake that stopped the operation of 12 power plants.

In areas served by Tokyo Electric Power Co. Holdings and Tohoku Electric Power, including the capital region, by January 2023, the level of reserves may fall to 1.5% of the volume of electricity generation, against the standard adopted in the country of 3.0%. In other regions, including the cities of Nagoya, Kyoto and Osaka, the level of reserves may be 1.9%.

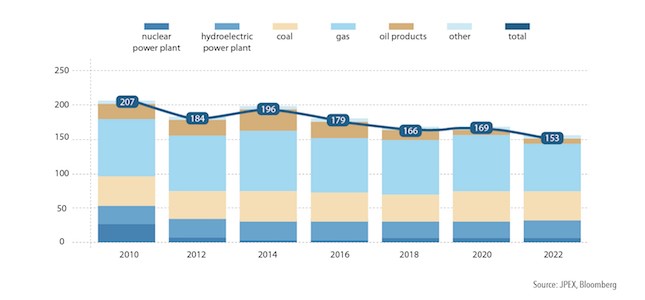

The problems in Japan's power industry are chronic and have been accumulating throughout the 2010s. The main one is a significant and almost progressive reduction in available power: in the fall of 2022, it was already 26% less than in 2010, before the accident at the Fukushima nuclear power plant. At the heart of this failure is the unresolved issue of restarting the operation of most nuclear power plants (of the 54 reactors shut down in 2011, only 10 have been returned to operation to date) and a sharp reduction in available capacities running on oil products. There has also been a reduction in available capacity in gas generation. The available coal-fired generation is stable but includes even stations that are half a century old, such as Takasago (Kansai region), built back in 1968.

In many ways, the current problems are rooted in the liberalization of the electricity market, carried out in 2016 and aimed at reducing the role of regional monopolies. Increased competition since then has led to a targeted and sharp reduction in spare capacity in the electricity industry, which fell victim to the struggle for cost reduction, which allowed for a time to reduce consumer prices. The main reduction was due to fuel oil generation.

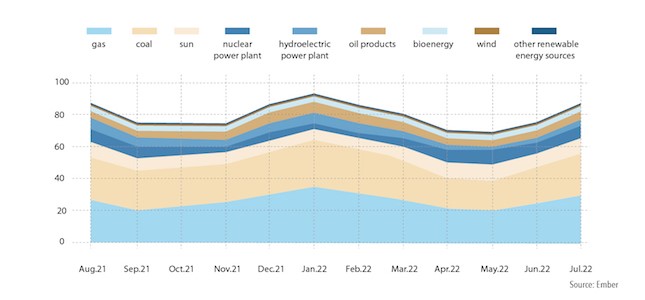

A sharp increase in recent years in the installed capacity of wind (4.5 GW at the end of 2021) and especially solar (74 GW) generation has not yet saved the situation (in 2021, they provided 10.2% of total electricity generation, according to ISEP).

As a basic and quick solution, the Government proposes restarting nine (out of 33 still idle) nuclear reactors that meet new safety requirements. Seven of the nine power units have already received permission from the regulator to resume work. A serious obstacle, however, remains the negative public opinion: nuclear energy, despite all the efforts of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, has not regained its former popularity among the Japanese. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is at risk of collapsing his rating, which has already been badly shaken since July, moving contrary to public sentiment. The Nuclear Energy Regulatory Authority, which requires strict compliance with all procedural deadlines for checking the readiness of nuclear power plants, does not follow the government's lead. In this regard, there is still no certainty that all nine nuclear power plants will be restarted before the end of winter.

Price factor

In its July review, the Bank of Japan revised up growth in the consumer price index (CPI, excluding fresh food) in fiscal 2022 to +2.3% from an April estimate of +1.9%. In the 2023 and 2024 financial years, the Bank of Japan expects inflation to decline to +1.4% and +1.3%, respectively (the April estimate was +1.1%). Although relatively low inflation rates compared to other developed countries, by the standards of the Japanese economy, it is frighteningly high, and the Japanese government intends to take additional measures to curb it. A detailed action plan is to be submitted in October this year.

The main problems are associated with high inflation (several times higher than the indicators noted above) in the segment of food products, imported essential goods, and especially energy resources. To combat the effects of rising prices, on September 9, the government decided to allocate targeted financial assistance to the 16 million lowest-income households in the amount of 50,000 yen (USD 350) per household.

The inflation problem is exacerbated by the Bank of Japan, which continues, despite the global trend, to pursue an ultra-soft monetary policy, typical of the "Abenomics" of the 2010s. He keeps his short-term interest rate on commercial bank deposits at minus 0.1% per annum, and the target yield on government bonds for 10 years is "near zero". At the same time, the Bank does not rule out further easing of monetary policy.

Against the backdrop of consistent monetary tightening in other major markets and a deterioration in Japan's trade balance due to a sharp rise in commodity prices, this approach has provoked a rapid devaluation of the yen since March. This has become an additional factor in accelerating inflation in the energy sector.

In order to curb the growth of domestic prices for motor fuels, in January 2022, the Japanese government introduced a system of subsidies for oil companies (ENEOS, Idemitsu Kosan, Cosmo Energy and others) to cover lost revenues in the event of an increase in world oil prices. The average price per litre of gasoline in the amount of 168 yen is used as a cut-off line. If market prices exceed this level, companies receive a subsidy of up to 35 yen per litre. The subsidies will continue to operate until the end of 2022, but in November and December, they are planned to be phased down to 30 and 25 yen, respectively. In January–August 2022, 1.8 trillion yen was allocated from the budget for the payment of subsidies.

The price issue is no less acute for electric power companies. Thus, at the initiative of the government, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and a number of private Japanese banks signed in October a loan agreement for the purchase of LNG with the country's largest electricity producer JERA in the amount of up to 130 billion yen (about USD 900 million).

Import from Russia is strategically important

Japanese energy imports from Russia have been volatile since March 2022, with the exception of LNG. The most volatile are Japanese oil imports. So, in June 2022, Japanese companies did not buy oil from Russia at all. Imports in July and August remained at a low level. Since all deliveries are made on a spot trading basis, they will remain highly volatile for the foreseeable future.

In March 2022, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan compiled a list of seven resources imported from Russia that would be difficult for the country to replace in the short term and, accordingly, should not be subject to sanctions restrictions. These included oil, LNG, coal, palladium, ferroalloys for steel production, etc. However, in April and May, the Japanese government announced its intention to gradually reduce imports of Russian coal and oil, although it does not plan to introduce regulatory restrictions against them.

At the same time, the lifting of sanctions on importing energy resources from Russia (LNG, oil, oil products, coal, uranium) is a matter of principle for the Japanese government since priority is given to the interests of national energy security. In addition, Japan is still determined to maintain an economic presence on Sakhalin Island, including in order to prevent the arrival of Chinese companies there that could replace the outgoing Japanese business (this applies primarily to the Sakhalin-2 and Sakhalin-1 projects).

In general, Japan's complete refusal to import Russian energy resources, especially Sakhalin LNG, is unlikely, given the availability of long-term contracts, relatively low contract value, as well as short transport leverage and logistics security.