One of the most high-profile international events of the first half of December was the visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping to Saudi Arabia. Many factors indicate that this was not just a "duty trip," but an important milestone in developing relations between the two countries and forming a new multipolar world.

What are the consequences of this event for the Middle East, the Asia-Pacific region, and the whole of global politics?

By diplomatic standards, the visit of the Chinese president turned out to be quite long—three days. Throughout these three days, on the sidelines of negotiations, Chinese and Saudi companies managed to conclude 34 investment agreements in various fields from construction to transport, from information technology to "green" energy.

It is estimated that the total value of these contracts reaches 110 billion Saudi riyals, or almost USD 30 billion. But it is not just about the amounts—it is the fundamental agreements between these two countries in such key areas as international security and energy that are important.

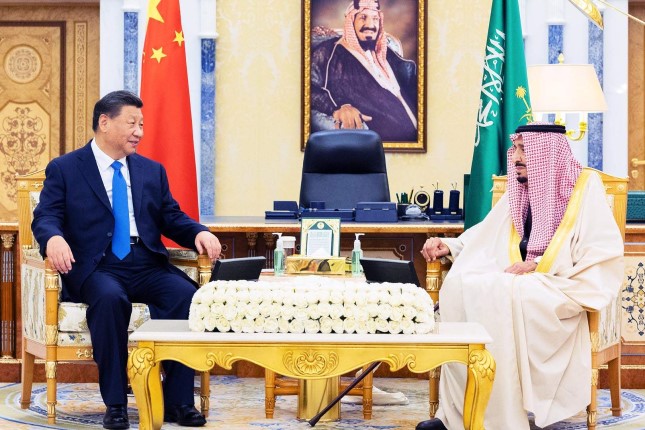

It is no secret that China is the world's largest consumer of energy today and that Saudi Arabia has been the third largest oil producer in recent years, trailing only the United States and Russia. Therefore, it can be assumed that energy supplies did not come in last place in the negotiations between Xi Jinping and King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud of Saudi Arabia.

And here a number of questions certainly arise for external observers, chief among them being: "Who are we teaming up against?"

Xi Jinping talks with King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud of Saudi Arabia.

China is now in a uniquely advantageous position in the global oil market. On the one hand, waves of anti-Russian sanctions are forcing Russia to reorient its supplies of "black gold" to new markets, primarily to the Asia-Pacific countries (mainly China and India). For example, Rosneft's share of the Asian space in terms of oil sales in non-CIS countries in the third quarter reached a record 77%.

It is known that Russian oil in Asian countries is sold at a so-called discount, and in fact—at fair prices suitable for both the seller and buyer, devoid of speculation. Thus, the Chinese economy has a powerful competitive advantage compared to that of EU countries, which are forced to purchase energy resources at a "political premium," actually paying out of taxpayers' pockets for anti-Russian sanctions. As a result, Russian oil supplies to China increased by 9.5% (to almost 72 million tonnes) over the first ten months of this year as compared to January-October 2021.

On the other hand, Russia still lags behind Saudi Arabia in terms of supplies to China. But the gap is minimal—the Saudis delivered 73.8 million tonnes to their eastern partner in the first nine months of this year. It can be assumed that with the introduction of the European embargo on the import of Russian oil and the price cap, the eastern vector of Russian energy policy will only see more action.

Does it bother Riyadh? We can assume so.

Of course, Saudi Arabia has reaped increased oil profits from the anti-Russian hysteria inflated by the West. And with the start of the European embargo, it will be able to partially replace the lower volumes of Russian supplies and increase its exports to Europe, and without any discounts.

But is the European oil market a worthy replacement for that of China? Is Riyadh ready to accept the possible loss of a certain PRC market share in exchange for an expanded European presence? Unlikely.

There is no doubt that China is the future, while Europe is only the past. Having lost its political subjectivity by surrendering to the will of overseas politicians and unleashing an economic war against Russia, Europe will inevitably pay for this with a prolonged recession, which, accordingly, will lead to a lower demand for energy resources. On the other hand, the Chinese market will grow rapidly, especially if Covid restrictions are lifted, and this trend is already outlined.

In these conditions, China has the opportunity, purely theoretical, to pit the two largest oil producers—Russia and Saudi Arabia—against each other, pulling them into a "battle of discounts" for its market. China could thus eventually start receiving energy supplies at the most favourable of prices.

But fortunately, Beijing is not Washington, and unleashing trade wars is not its style. Speaking at the UN in 2015, Xi Jinping proposed the creation of a "community of the common destiny of mankind" as a response to the escalating global challenges. In fact, the Chinese leader wisely appealed to the world: we are all in the same boat, so we must not rock it. Unlike the West, China is trying not to divide, but to unite mankind.

Therefore, perhaps one of the goals of Xi Jinping's visit to Saudi Arabia was not to unleash another "oil war," but on the contrary, to prevent possible conflicts between the largest suppliers of "black gold."

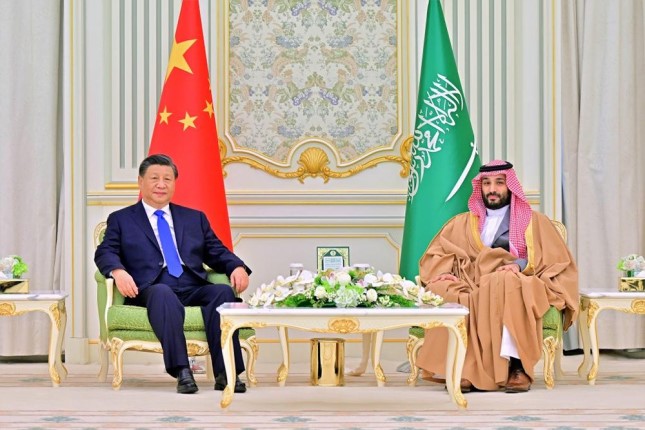

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Crown Prince and Prime Minister of Saudi Arabia Mohammed bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud held talks in Riyadh at which Xi Jinping noted that Saudi Arabia is an important member of the Arab and Islamic world, as well as an important independent power in the multilateral world and an important strategic partner for China in the Middle East.

And it should be admitted that these seeds of Chinese wisdom fell on fertile ground. Riyadh and its Middle Eastern allies have already shown that they are not going to take advantage of Western anti-Russian sanctions to try to force Russia out of the global oil market. OPEC+'s October decision to cut production by 2 million barrels per day is a clear declaration that the Saudis do not intend to play the political games imposed by Washington.

The balance of the oil market should be calculated on the basis of real volumes of supply and demand, and not on Washington's desire to exclude this or that supplier from the international trade system. And apparently, this approach is shared by official Beijing.

In addition to economic aspects, the two leaders surely did not ignore issues of global security, which are becoming more and more acute for the Middle East today.

In fact, we are witnessing the destruction of the long-term Washington-Riyadh strategic alliance, which for a long time was the foundation of the region's security. While maintaining its military presence in the Persian Gulf zone, the United States is at the same time visibly losing prestige in this part of the world and losing its ability to influence the resolution of existing contradictions between the forces at play here.

A clear indication of the White House's weakening influence is the same October OPEC+ agreement. Recall that former US President Donald Trump quite skillfully orchestrated (including with the help of Twitter diplomacy) the conclusion of the so-called OPEC+ 2.0 deal, as a result of which Russia had to succumb to Riyadh's conditions and significantly reduce its production. Current president, Joe Biden, has demonstrated his absolute inability to somehow influence the decision of the Saudis and their allies to reduce production. Neither threats nor even humiliating pressure have helped.

In the context of the US's Middle East failure, the need to create a new architecture of security is growing both in the Middle East and in the Asia-Pacific region as a whole. And China, with its doctrine of peaceful coexistence of all peoples, could be one of the pillars and guarantors of such security.

Of course, there are still many difficulties and pitfalls. In particular, official Tehran negatively reacted to the fact that during his visit to Riyadh, Xi Jinping discussed the issue of the ownership of three disputed islands in the Persian Gulf (claimed by both Iran and UAE).

But in any case, the trend is obvious: the Chinese model of peaceful coexistence is proving to be more attractive for the countries of the region than American military hegemony. And the emerging contours of the new world order are drawn, among other things, by oil.

Reliable and equal cooperation in the energy sector could become the basis for the formation of entirely new political alliances.