European fashion trends are a huge problem for northern Africa.

Landfills are maxing out their capacity, dyes from clothing are flowing into rivers and the sea and covering beaches, turtles are unable to make it to the beach, the coral is dying, and fishermen can't fish.

"It's an environmental catastrophe," says Solomon Noi, a member of a Ghanian delegation that recently visited Brussels to explain the problem and to try to get the European fashion industry to step up and take responsibility.

But what on earth does European fashion have to do with environmental problems in Ghana and elsewhere?

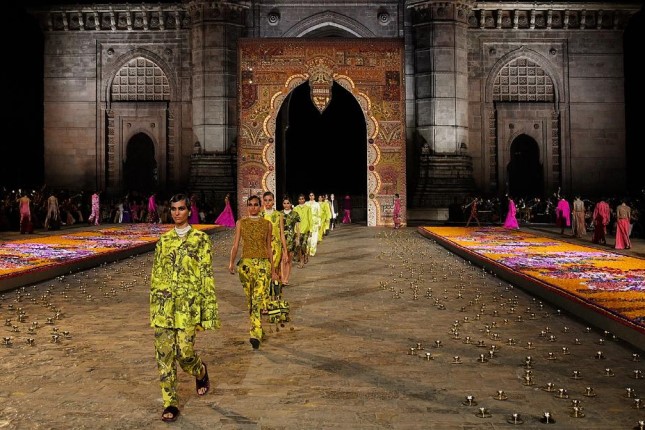

The problem is the growing trend of what is known as "fast fashion."

Fast fashion is a business model that involves the rapid production and sale of inexpensive clothing that is designed to be worn only a few times before being discarded. This trend has been driven by several factors, including the rise of e-commerce, the increasing demand for low-priced clothing, and the desire for fast and frequent turnover of fashion styles.

Some of the leaders in fast fashion include Zara, H&M, Forever 21, Primark, Topshop, Uniqlo, and Mango. These companies are known for producing and selling trendy clothing at low prices, with a fast turnover of styles. However, they have also been criticized for their negative impact on the environment and for poor labor conditions in their supply chains. In recent years, some of these companies have made efforts to improve their sustainability and ethical practices, but the fast fashion industry as a whole continues to face scrutiny for its impact on the environment and society.

Returning to Ghana—the country has traditionally been a major producer of textiles, but the rise of fast fashion has had a negative impact on the local industry as well as the environment.

One of the main issues is the amount of textile waste that is generated by fast fashion. Many fast fashion brands produce clothing quickly and cheaply, using low-quality materials that are not designed to last. As a result, consumers often discard these items after only a few wears, leading to a large amount of textile waste.

This textile waste often finds its way to secondhand markets in West Africa, and Kantamanto Market in Ghana is one of the largest. It's estimated that thousands of tonnes of used clothing, including fast fashion items, are imported into Ghana every year. According to the Guardian, the market handles about 15 million garments a week and provides work for about 30,000 people.

But even a market covering 18 acres of land cannot handle such a volume. About 6 million of the better-quality items are sold every week, but about 40% is simply discarded as waste, and fast fashion is pushing this number higher and higher. The drop in quality only leads to more waste and lower earnings for traders. Many are finding themselves in debt.

The capital city of Accra, where Kantamanto Market is located, was simply unable to cope with the sheer volume of garbage. Ten dumps hit capacity and had to be closed between 2010 and 2020, and now waste is transported to a dump 30 miles away, which can actually only handle about 30% of the total clothing waste—the other 70% ends up in ditches and drains and on the beach.

"Kantamanto makes visible the problem that exists in Europe," says Samuel Oteng, a designer with the Or Foundation, a Ghana-based environmental organization that works with Kantamanto. Or funded the Ghanian delegation's recent trip to Brussels, where, in short, they called for regulations to ensure that Ghana gets some financial help to deal with the 100 tonnes of clothing discarded from the market every day.

The Or Foundation is not pulling any punches in its "Waste Landscape" report from January 2022.

Fashion waste exists in Ghana because we have manufactured a crisis. We have decided that a garment is no longer fashionable, costing us everything because we have made clothing that costs nothing. We produce excess, slash prices, replace what we never really wanted with more of the same and we pass on the burden to someone else. The reality of the waste landscape is that homes are bulldozed, businesses are burned, a mall is built in their place, more clothing is produced than anyone knows what to do with, and we are poisoned by our own desires. Someone makes these decisions. We all do. They add up.

Of course, the problem is not limited to Ghana. According to Oxfam, a confederation of charities focused on alleviating poverty, 70% of clothes donated worldwide end up in Africa. In 2015, members of the East African Community – Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda – announced plans to ban secondhand clothing imports. However, in the end, all but Rwanda caved in to pressure and threats from the US. Despite severe sanctions, Rwanda's own textile and garment industry is showing great promise today.

And at least one man in Uganda has another, unique response to the problem of fast fashion textile waste. Bobby Kolade spent 13 years in the European fashion world before returning to Uganda in 2018. Inspired by his experiences in Europe and his memories of buying used clothing at Uganda's biggest market, Owino in Kampala, he came up with the idea of repurposing the cheap and used clothing flooding his country.

His company, Buzigahill, is all about "redesigning secondhand clothes and redistributing them to the global north, where they were originally discarded before being shipped to Africa," Kolade told the Guardian.

Besides the environmental problem, Kolade also finds the situation offensive to the people of his country:

I see these clothes, and they offend me. I see white shirts with sweat stains and torn colors, and I feel oppressed. What does it say about whoever's donating those clothes to us? And what does it say about our position in the world? It's rude, you know? It's really rude.

Thus, Kolade conceives of his project as a "reactionary design" to the consumer gluttony of the Global North, and the role Africa plays as "a very effective waste disposal system for people's clothes."

And the whole fast fashion life cycle of clothes not only ends with disrespect for the little guy, but it starts that way too – the trend has been criticized for the poor labor conditions of workers in countries such as Bangladesh, China, India, and Vietnam who work in classic sweatshops: low wages, long working hours, and unsafe working conditions. By outsourcing their production to factories in these countries, fast fashion brands manage to largely evade labor monitoring. Some brands have faced criticism for their lack of transparency and for failing to address labor violations in their supply chains.

For one case in particular, a factory in Turkey that supplied clothing to Zara was accused of exploiting Syrian refugees in 2017 after customers found strategically placed notes in items they bought, with messages such as, "I made this item you are going to buy, but I didn't get paid for it." Workers say the factory they worked in closed down overnight, and they were owed three months of pay as well as severance.

Zara responded to the allegations by stating that it had conducted an investigation and had terminated its relationship with the factory. However, critics argued that the company had not done enough to ensure that its suppliers were following ethical labor practices and had failed to address the root causes of labor violations in its supply chain.

This incident highlighted the need for greater transparency and accountability in the fashion industry. Several other brands have faced similar accusations.

In short, fast fashion is an all-around disaster. Not only is the trend itself just another sign of the reigning vacuousness in the First World, but it also robs people of their dignity and their money throughout the production – waste cycle, and it is just as much of a disaster for the environment.

The Ghanian delegation to Brussels wants Europe to ensure their country receives funds towards managing the tonnes of clothing that flood their markets every day. France is currently the only country in Europe that has an extended produce responsibility regulation that covers the textile industry, and critics say the program as is does little to nothing to help anyways.

The fast fashion problem has been well known for several years now, and still it persists. And according to the Or Foundation, the European Commission's latest proposal "do[es] not stop Waste Colonialism… not based on a sound understanding of the structure and practices of the global secondhand clothing trade."

"What's missing is a willingness to incorporate the realities of the people most deeply impacted by fashion's waste crisis and to support the solutions taking shape in those communities," the Foundation writes.

But Europeans get to look good for cheap. Forget the rest of the world.