You may not know it, but when you buy Bulgari perfume at your local mall, then head to the jewelry store for a Tiffany necklace, then to the wine shop for some Dom Pérignon, in reality, every penny you're spending goes to the same place—to LVMH.

LVMH was created in 1987 as the merger of the fashion house Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy, the famous alcohol manufacturing company.

Since then, it has become quite a sensation.

The company has expanded to sell products from 75 luxury brands (and counting), and its managing director, Bernard Arnault, 74, became the richest man in the world last year, surpassing even Elon Musk and Amazon's Jeff Bezos. According to Bloomberg, his fortune stands at EUR 212 billion, while the company made a profit of EUR 14 billion last year.

And just as LVMH began as the merger of two unrelated companies, so Arnault's secret for success lies in the merger of two seemingly incongruent ideas: luxury and mass appeal.

"Striving for social status and recognition is something deeply human," says Frank Muller, a lecturer at the University of St. Gallen and a consultant for luxury companies. "This has been the role of luxury since ancient times: to give people a sense of special identity."

And thanks to Arnault's ever-expanding LVMH colossus, this "special identity" is more and more a thing for the commoners. Arnault is an "intellectual visionary," says Muller.

And not only is Arnault a "visionary," but he seems to have a bit of a cutthroat streak in him too. Back in the 80s, he convinced the French state to sell him the insolvent Boussac for the symbolic price of one franc, and he quickly set about restructuring things after his own vision. He laid off 9,000 employees and sold off all the businesses except Christian Dior and the Bon Marché department store. The move earned him the moniker "The wolf in cashmere fur."

From there he got himself hired at LVMH in 1987, and eventually managed to oust the bosses of Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy from their family businesses and appoint himself president of the group in 1989.

And Arnault has continued this course of company takeovers to this day. For example, he purchased the fashion company Givenchy in 1988, watch manufacturer TAG Heuer in 1999, suitcase manufacturer Rimowa in 2016, and jewelry manufacturer Tiffany in 2021.

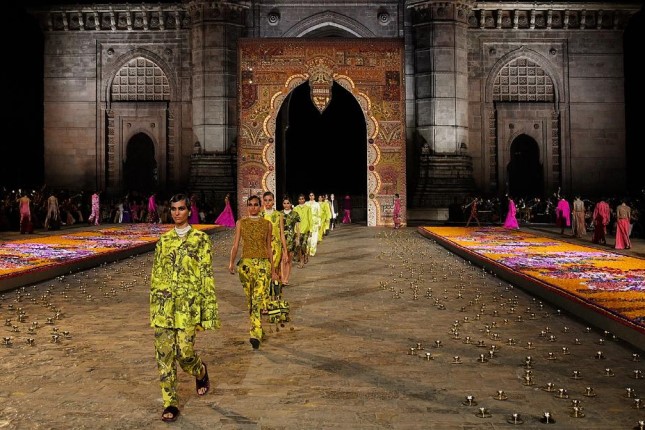

Once in control, he tweaks their luxury items to disseminate them to the masses. When he got a hold of Luis Vuitton in the 80s, it was known exclusively for its elegant suitcases and bags. But in the late 90s, those elegant bags were put out with bright graffiti print all over them. "Suddenly they looked like street clothes," writes the German outlet Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

Industry insiders initially criticized Arnault's strategy, but he stood his ground and proved his case, and today, LVMH accounts for 20% of luxury goods sold worldwide. Over the past 20 years, company profits have increased twenty-fold, from EUR 700 million to EUR 14 billion.

And that kind of cash attracts superstars. Among those representing various LVMH brands are Ryan Gosling, Anya Taylor-Joy, Beyonce, and Jay-Z, and its most important celebrity faces are Rihanna and Pharrell Williams.

And that kind of star power attracts young people who hang out on social media "where their idols show them what to wear," in the words of NZZ.

But then again, maybe not all young people can afford a Dior dress, but why not Dior perfume, or Dior lipstick, or Dior sneakers? Such "entry-level" products allow new fans to own something from the brand and show off a bit. Arnault's hope is that such customers will graduate to more expensive products as they grow older. But for now, brands like Louis Vuitton are making more money on T-shirts and sneakers than high fashion.

Vuitton and the other brands have a clear message: "We are a way of life."

Of course, all this necessarily raises a question: If more and more people can afford this "way of life," is it still a life of luxury?

"When everything turns into a homogeneous mess, the elitism of luxury is no longer there," comments Frank Muller. And if the elitism of luxury is not there, the motivation to fork over large sums for those products is no longer there.

The balance between luxury and mass appeal is not an easy one to maintain.

For now, LVMH is the hottest thing going, and Arnault is filthy rich. But the question is, how long can this situation continue?