In April 2022, Christine Lagarde, head of the European Central Bank, visited the World Bank and IMF 2023 meetings in Washington. On and immediately afterwards, she made a series of statements that were widely circulated in the press - including on such a traditionally sensitive topic as a possible US default. Although the statements of the former IMF head, now at the helm of Europe's economy, were optimistic, there is severe tension behind them. So will there be a default?

From an economic perspective, few shocks are more significant than a default. Argentina and Russia showed back in the 1990s that immediately after a default - instantly, even before the real economy shrank - the number of deaths from heart attacks and strokes started to rise significantly. Similar phenomena in developed countries, even from stock market panics, no longer occur (after 1929). Defaults are essential because they undermine the economy's very basis: the trust of agents in the state and, ultimately, in each other.

Of course, there are also defaults from which nothing happens. For example, the Russian economy experienced a technical default in 2022 (its authorities could not pay its debts in Western currencies because of sanctions), but it did not impact anything. Nevertheless, this is the exception, only confirming the rule. Is the implementation of this rule possible for the US?

The technical and economic aspects

Default on the national debt of the USA is technically possible only in one case: if the USA wants it. Because that debt is denominated in dollars, which the Fed has repeatedly printed trillions of dollars a year, it is technically easy for the Fed to "print" tens of trillions of non-cash dollars tomorrow and use them to buy all government bonds without defaulting. Then again, the Fed has already done something similar by purchasing a large amount of US bonds.

Of course, that does not mean that the USA would be happy with this course of action. In such a case, some foreign holders would want to exchange their dollars for national currencies after selling government bonds. In that case, there would inevitably be significant dollar depreciation against the yuan and, most likely other world currencies. This will spur dollar inflation, and more importantly, it may scare foreign investors who have invested in other state assets - stocks and bonds of private companies and so on. An additional wave of capital flight may further weaken the dollar and push up US prices.

Thus, while Washington can avoid a formal default by printing any amount of dollars if it wants to, in real life, such a situation is undesirable. In terms of maintaining macroeconomic stability, it is more advantageous to maintain the status quo: to pay the interest on government obligations, even if it puts a heavy (more than a trillion) burden on the national budget.

The political dimension: perilous waters

The existence of an objective possibility of avoiding default does not mean that it will actually be avoided. Rafael Correa did not default on Ecuador's debt in 2008 because he couldn't pay it: the very idea of such a debt seemed immoral to him.

In the US, the situation is even more acute. In the local political culture, a culture of compromise has tragically declined. While Republicans and Democrats under Bush Jr. knew how to negotiate, since 2011, the opposition party has traditionally accused the ruling party of racking up the debt. And each time it delays approving a new borrowing ceiling for the government, it creates a situation where it could formally go into default. The mechanics are simple: if a new borrowing ceiling is not approved, the budget expenditure will exceed the income to such an extent that there will be nothing left to pay the interest. That is enough to cause a default.

Characteristically, a new ceiling is haggled over every year. Every year the opposition party literally extorts concessions from the ruling party in exchange for all but inevitable agreement to raise the ceiling. This blackmail makes the market players nervous, who, before 2011 - before the regular political bickering in Congress on this subject began - never even considered the possibility of a US default.

What prompted Lagarde's comments?

In January 2023, the US national debt reached the previous ceiling of $31.4 trillion, following which the US Treasury undertook a series of manoeuvres to create an $800 billion "cushion" against default. Together with tax receipts, the wave of which occurs in the US in April, this blocks the possibility of a default in the spring. But in the summer, the ceiling is either raised or the possibilities for postponing it are exhausted.

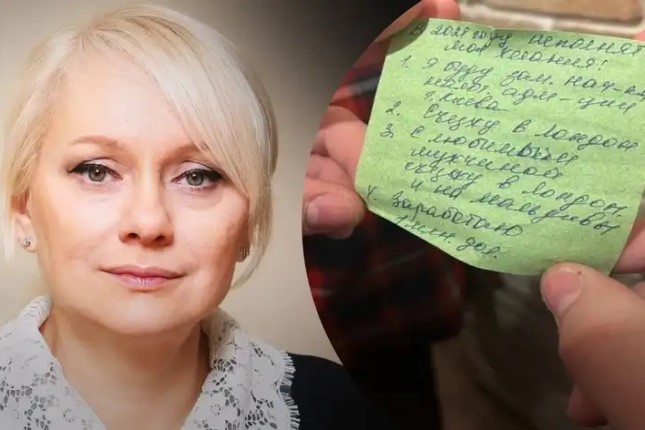

Not surprisingly, on April 16, 2023, Christine Lagarde publicly told CBS:

"I have huge confidence in the United States, I just cannot believe that they would let such a major - major - disaster happen. If it did happen, it would have a very, very negative impact not just for this country, where confidence would be challenged, but around the world, I understand the politics, I've been in politics myself. But there is a time when the higher interest of the nation has to prevail."

This sends a clear message to US elites: the desire of US Republicans to tie a ceiling increase to a reduction in US government spending must be abandoned. Biden has already said he would not accept such a deal. Since there are doubts about his willingness to compromise and whether he is even aware of the nature and dangers of what is happening (suffice it to recall that he recently failed to identify the British leader, shoving him aside in a personal meeting), it is clear that the compromise will have to be made by someone who is still able to recognize others and understand the relationship between his decisions and the risks to the economy - such as Republican leaders.

Lagarde's call sounds more like a good play in a bad game than a real sign of confidence. In 2011, in a similar situation, Democratic President Barack Obama went along with Republicans to cut government spending by $2 trillion - and in exchange, Republicans raised the debt ceiling. Now House Speaker Kevin McCarthy of the Republicans expects a similar deal. He continues to act as if it's back to 2011 and the USA still has a president who understands where he is and what's going on around him.