Reed Hastings, one of the founders of Netflix, did not bold back when talking about the movie business back in 2017, insinuating that it has long since become outdated. The only innovation cinemas managed to offer viewers over the last 30 years, he said, was better popcorn. Meanwhile, Netflix, he insisted, intends "to unleash film."

But what is holding the movie industry back and how is Netflix "unleashing" it? Will Netflix and other lesser-known local streaming services, following its model and experience, make us forget about the good ol' moviegoing culture, or is it rather a replacement for watching movies on TV? And how does streaming change the viewer's experience? What kind of new culture does it create?

In other words, what monster is eating away at our brains while we sit at home streaming?

These are indeed worthy questions that demand an answer.

When it first started in 1997, Netflix, a company that has become practically synonymous with the new streaming culture, was but a modest DVD subscription service.

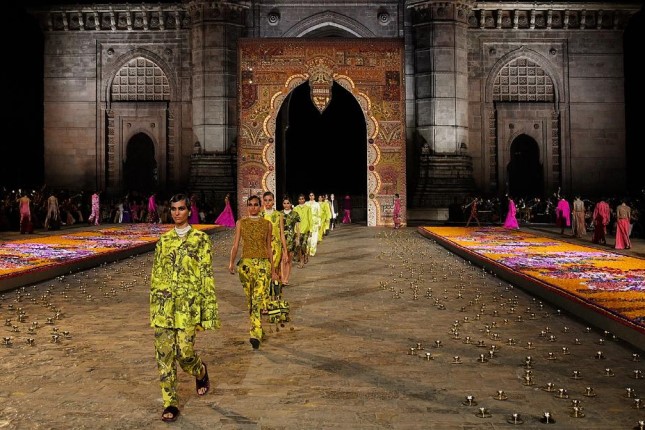

However, by 2013, it had expanded to the point of gradually creating its own content − both feature films and series, developing its own vivid style. Since then, the company has gone international, shooting productions here and there around the globe, thereby drawing even more viewers from around the globe and capturing markets in Asia, Africa, and Europe.

That is what distinguishes Netflix from other successful streaming services that do not have such global ambitions. Today the service has more than 230 million subscribers, with only 63.1 million of them from the US. Company revenues amounted to USD 31.6 billion in 2022. Thus, it is indeed a serious contender, a competitor to American streaming services such as HBO (producer of the legendary Game of Thrones series) and major Hollywood companies.

Netflix's modus operandi is to tap into the niche of modern cinematography in developing countries by hiring fresh young filmmakers. This, in turn, has stimulated the blossoming of small local streaming services, which in many ways imitate American services but yet manage to grab some cash by creating tension in local markets thanks to their greater immersion in the issues and aesthetics of their respective countries.

So, Netflix is Hollywood's naughty kid, its prodigal son, constantly returning to its source. Being a trigger for contemporary filmmaking around the world, it may seem like a liberating power − think of the Indian hit Sacred Games or the German series Dark, about a fear of nuclear plants. It also sometimes comes to the rescue of risky projects that big film companies refuse to release − a striking example of this is Martin Scorsese's 2019 film The Irishman, with its USD 159 million budget, which was first rejected by Paramount Pictures.

But, while some think Netflix is the great hope for independent cinema, it may well prove to be quite the opposite.

True, American movie culture is an expansive thing, designed for worldwide consumption − Hollywood has been imposing its trends upon the rest of the world for decades − but Hollywood itself remains quite indifferent to cultures from outside of North America. Its representations of other countries, societies, and cultures are notoriously simplistic, stereotypical, and above all, uninterested. The same applies to other American streaming services like HBO, Hulu, and Disney+, and that is why their popularity is limited mostly to the American market.

The Netflix model is rather different, truly global in terms of content. If you will, it delves much deeper, showing authentic local stories from Asia, Eastern Europe, or the Middle East through the same lens of identity and tolerance politics, claiming democratic values in the setting of each particular culture and capturing minority voices.

But Netflix is not interested in discovering local authenticity, but only in exploiting it to promote the liberal agenda (gender equality, feminism, sustainability) and establish its ideological framework. This homogenizing lens is the cost of Hastings' "unleashing of film," and this is why Netflix movies have such a recognizable style − the aesthetic forms of local cinematic traditions are practically erased.

The same thing happens to our mindset as viewers of such content, by the way. Cultural differences are silently and deceptively corroded so we feel closer to those other cultures. But it is just an illusion, and the filmmakers know exactly what they are doing. So, we can easily move through cultures on the platform − the aggregator guides the trip, and we don't even have to think about what to watch. With such a toy, we can actually pretend the world is so uniform and easily navigated.

But thankfully, the magic of an encounter with truly different cultures still exists, and it is still happening in physical cinemas all over the globe. Hundreds of international film festivals are held every year. And here's hoping that we never trade all this polyphony for the illusion of a unified and homogenized world.

Going to the movies is like a ritual, creating a fragile, anonymous community, with people sitting together in the same dark theatre, united by the common emotions elicited by the film they are watching. These temporary affective cinematic communities are crucial for maintaining urban culture as we know it. And this is precisely what streaming services cannot provide.

The pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 were a time of triumph for streaming services and a disaster for cinemas. But with the end of lockdowns throughout the world, the film industry is quickly recovering. When given the chance to have our better popcorn again, we rushed back to the theatre.