Since the middle of the 20th century, demographers have been asserting that there is an inverse correlation between a nation's wealth and its birth rates. Recent studies show that this may not necessarily be the case. While it is true that as far back as the 1960s, it was shown that, in a developed country, a household's higher average income is a predictor of a smaller number of children in that household, this trend has recently experienced a reversal. That is because a person's financial status is not the only factor influencing their desire to start a family. There may be other factors at play here as well.

Over the last few decades, rich countries' replacement rate has dropped to 2.1. This means that an average couple produces two children, which helps sustain the population's current level. Also, statistically, an additional 0.1 children allows the population to grow, albeit at a slow rate. That said, the situation in some countries, such as South Korea, could be described as catastrophic, as the nation's total fertility rate has fallen to 0.81. Whereas in 1950, on average, one woman gave birth to 5 children, nowadays this number has dropped to 2.5.

But in some countries, the situation is gradually improving. Recently, the US has seen its fertility rate rise from about 1.75 to almost 2.5. Similar trends have been observed in Scandinavian and Western European countries. One might suggest that this could be attributed to the inflow of migrants from countries where families traditionally tend to have more children. However, this argument was refuted by research showing that middle- and high-income families lead the way in the childbearing department. Interestingly, the more a mother of a family makes, the more children she is likely to have.

According to demographers, women usually choose not to have children for purely pragmatic reasons. It is generally more costly to raise a child to a point where he or she can become self-sufficient in a developed country than it is in a developing one. Hence, the popular sentiment that it makes more economic sense to "focus on quality rather than quantity". Besides, giving birth to a child often means that the mother would have to put her career and social life on hold. Research has shown that, until their children are fully grown, parents, on average, tend to feel less happy than childless couples. That said, if one were to examine the parents' entire lifespan, and not just the rough patch spent rearing up their growing offspring, then the situation would be reversed: childless families are generally more unhappy in the long run.

Common sense suggests that if the pressure on parents, and women in particular, could be slightly lower, they would be more likely to opt for having children. Indeed, countries that boast more sophisticated and expansive public childcare programmes offering mothers longer maternity leaves and making them more likely to be eligible for government benefits tend to show higher fertility rates. Additionally, more children are born in countries where fathers are willing to contribute a greater deal to taking care of their offspring and are prepared to take a parental leave themselves, too, or to do household chores that more traditional societies regard as those reserved just for women. Besides, women who can afford to hire domestic help, such as nannies, housekeepers, etc., tend to be more likely to want to have children. In other words, they have to be well-off.

Increasingly, a growing number of low-birth-rate countries are starting to take these factors into account. South Korea, for one, now offers women a one-year-long maternity leave plus another year when they are entitled to spending a reduced amount of time at work. In Hungary, women who give birth to or adopt four or more children are exempt from income tax for the rest of their lives. On average, the government of Norway spends more than USD 29,000 a year per child.

It is worth noting, however, that money and support seem to work better in some societies than they do in others. Researchers put this down to such an important factor as the cultural context. In other words, it is not enough to offer women an opportunity to have children and keep their jobs, nor is it sufficient to support them with just monetary and other kinds of benefits. What is equally crucial is to make caring for one's offspring and performing other important roles socially acceptable and welcomed. Many cultures, especially the more traditional ones, simply do not approve of mothers paying less attention to her children while spending more time with their friends or at work, making women think twice before deciding to procreate.

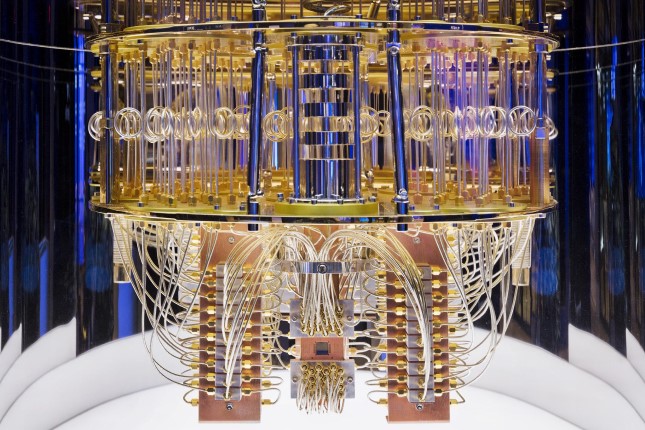

Emerging technologies could also be increasingly useful in making childbirth and parenting more affordable for modest-means families. With the number of older people on the planet projected to exceed one half of the world's total population by the middle of the 21st century, babysitters and housekeepers will be in greater demand and, therefore, less affordable. But help could be on the way in the form of robots and artificial intelligence, and by working from home, women would be able to look after their children, too.