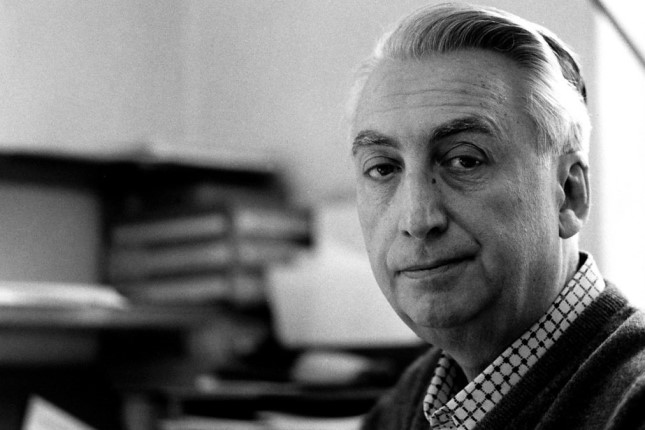

In 1967, culture theorist Roland Barthes published a provocative essay entitled "La mort de l'auteur" ("The Death of the Author"), which stood as a manifest of the rising postmodern culture. The prominent French intellectual argued against such notions as "the author’s intention," instead putting the main emphasis on the crucial role of the reader in shaping the meaning and interpretation of a given literary work.

In Barthes's concept, the author no longer has any authority, giving way to the "scriptor" − a new type of postmodern writer devoid of any subjectivity, personal experience, or human intentions. The scriptor can no longer be called an author, since he, she, or rather it, does not experience any "pangs of creativity," but is only a modest compiler of various texts in a certain order.

Fifty-five years later, with the advent of AI technologies, Barthes' essay reads like a prophecy.

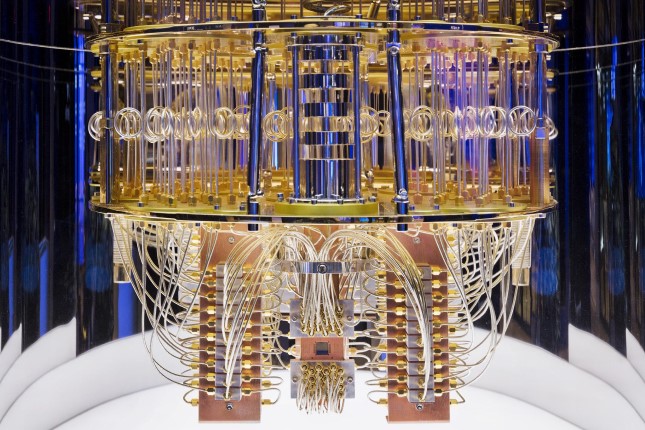

When a new AI chatbot called ChatGPT was unveiled to the public a month before Christmas, it was showered with accolades and the program immediately went viral. "ChatGPT is scary good. We are not far from dangerously strong AI," tweeted Elon Musk a few days after it came out. By the end of January 2023, ChatGPT had already amassed millions of users. Google considers it the most dangerous competitor the company has ever seen.

With the advanced technology of natural language processing, the chatbot is quite good at maintaining natural-sounding written conversations and producing texts that are almost indistinguishable from those written by humans.

Chatbot can provide sensible answers to questions posed to it, write essays on a given topic, and even compose very mediocre poetry. Tell it to write a Shakespearean-style poem about the cold of winter, and in about a minute you’ll get something like this:

Oh winter, thou art cold and harsh,

Thy breath doth freeze the very air,

And make the trees to creak and hark,

As if in sorrow and despair.

Thy days are short, thy nights are long,

Thy winds doth howl and moan and wail,

Thy snow doth fall in endless throngs,

And make the earth a frozen pale.

And so on, and so forth.

At this point, copywriters, journalists, novelists, script writers, and everyone else in the writing business might be feeling a bit uneasy, but actually, they need not be worried that AI is going to take their jobs, at least not for the time being. The prose texts generated by ChatGPT lack imagination and originality, and are actually extremely unentertaining. It seems the aim is simply to include all the required information, rather than evoke emotions or command the reader's attention.

Rather predictably, some cheeky college guys immediately began using ChatGPT to write their essays, which they started turning in to professors as early as a week after the chatbot was released. And in fact, ChatGPT is capable of producing work on the level of a studious college freshman, with a smooth, flowing text and practically no stylistic errors. However, its texts are totally lacking in any trace of original thinking and often include well-composed misinformation (remember: it is not an author, but a scriptor, so it has no authority and bears no responsibility for the texts it generates).

The problem for educators is that unlike earlier forms of plagiarism, it is difficult to detect AI cheating with 100% certainty, and even more difficult to prove. There are tests that estimate how likely it is that a given text was AI-generated, but there is always a chance that it was not, and if the student does not confess, there is no way it can be decisively proven.

Still, if you want the bot to write a creative essay for you, editing is indispensable, otherwise the text will probably be a standardized, pale imitation, with repetitious speech patterns. At the same time, the bot does not focus on details and content − its output is limited to general information, and its analyses are superficial fluff.

However, it is still a good tool for creating any structured texts, such as to-do lists or questionnaires. As such, it can be useful for educators, medical professionals, civil servants and lawyers, office staff, and it will probably soon be accepted in fields involving various kinds of bureaucracy, but again − it cannot replace a human being.

It is also claimed that the bot can write code in the major programming languages. However, software developers also need not worry for the time being. ChatGPT is amazingly smart − it can code some simple programs and even debug its own code, but the quality simply is not very high. Experts agree that ChatGPT and AI in general could soon become a useful tool in software development and a helping hand for unskilled individuals who need to write some simple code. But for now, AI is quite far from being a worthy substitute for qualified human professionals.

However, ChatGPT is still a true sensation and the new king among AI chatbots. But to correctly assess its potential impact on the economy and the labor market, we must bear in mind that the bot is more efficient the more routine (requiring less creativity) the operation it performs.

AI is truly a realization of Barthes' concept: Being a scriptor rather than an author, it only connects and recombines signs according to patterns, and therefore is doomed to remain at the level of mediocrity. For sure, AI may soon be capable of writing a good synopsis of what is already known, but not an original research paper that extracts new knowledge and provides original insights; it can be strong at stylistic imitation, but cannot develop its own original ideas and writing style; it may be helpful in producing simplistic code, but not in creating ideas that change the world.

And as such, it is indeed a brilliant imitation of mediocrity.