As Russian gas deliveries are shrinking, European countries have started to tap into their winter reserves that risk being depleted by as early as January, according to a forecast by Wood Mackenzie, a global commodity and energy consultancy. Germany, France, Italy, and Austria are facing the risk of being the hardest hit.

In the face of an unprecedented heat wave sweeping across the continent coupled with a limited supply of natural gas, the European Commission has proposed cutting natural gas consumption by EU member states by 15 percent and getting itself empowered to coordinate distribution of the remaining volume. In a gesture that illustrates apparent lack of unity in the ranks of the EU, Spain, Germany, France, Italy, Poland, Hungary, the Netherlands, Ireland, and Greece refused to support this initiative.

President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen

The EU has set its sights on filling Europe’s natural gas storage facilities to 80 percent of their capacity by November 1 compared with the current figure of about 65 percent. These volumes of gas could prove to be adequate provided that Europe only uses the gas strictly to meet the needs of its citizens and social infrastructure facilities, but not if it decides to also direct some of it to support its manufacturing industries. The implication is that Europe could still face the need to partially de-industrialise and move its manufacturing industries to more power-rich regions.

Underground gas storage

However, there is consensus that this problem could be solved by using gas from Russia, the region’s traditional supplier of cheap energy. But there is a catch: EU officials would have to admit that they got too carried away waging the war of sanctions against Russia. Perhaps some of the statements made recently by a number of European politicians may be indicative of a trend towards emerging pragmatism.

“The key word is gas”, Austrian Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenberg said in his recent statement and added that “there used to be a tough discussion that we should stop getting gas from Russia, and we, like a number of other EU countries, clearly said – this is not up for a discussion, because it would greatly affect us”. Vienna is 80% dependent on the Russian gas while buying the balance form its neighbors (who are likely selling it the very same gas from Russia).

Hungary, that until recently had been one of such resellers, sent its Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto to Moscow late last week to attempt to secure additional quantities of gas. According to Szijjarto, “the reality is that without Russian sources it would not be possible to buy an additional 700 million cubic meters of gas. Some may sell empty promises and chase dreams, but the physical realities cannot be changed.”

Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjártó at joint press conference with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov

According to Bloomberg, citing Gergely Gulyás, the chief of staff for Hungarian Prime Minister, Hungary has declared “a state of emergency” in its energy sector. According to Gulyas, Hungary’s plan of action under the state of emergency entails banning energy exports “in most cases”, starting on August 1, while at the same time trying “to buy additional quantities of natural gas on the market to supplement its depleted stocks".

By and large, when it comes to buying more gas, Hungary finds itself in a very privileged situation on account that Budapest can import gas both from the South (LNG from the Middle East and pipeline gas from Central Asia), and from the east (Russia’s pipeline gas). This sets it apart from other members of the EU who, either for reasons of their geography or due to their principled and politicised stance, are severely limited in their choice of gas suppliers.

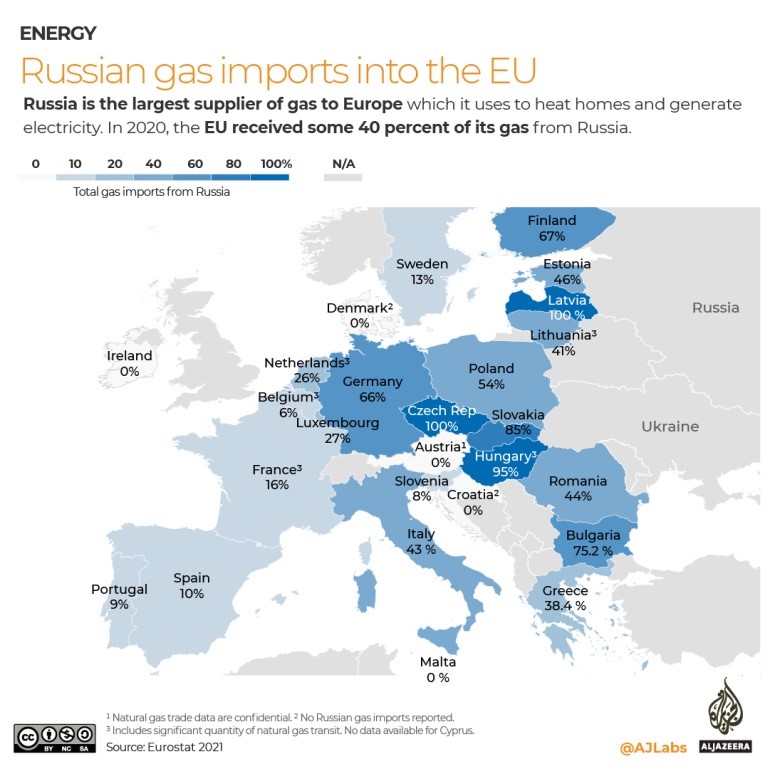

Gas supplies via the Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline

According to Eurostat, Budapest has been importing in excess of 110 percent of the gas it needs from Russia, managing to successfully resell any excess quantities. Other East European countries, too, have been relying on Russian gas imports, albeit not as profitably. Bulgaria used to buy more than 90 percent of the gas it needed from Gazprom, while Slovakia and the Czech Republic were covering more than 70 percent of their gas needs by buying from Russia, whereas Greece’s numbers fluctuated between 45 and 55 percent depending on the season.

By contrast, France has been buying most of its gas from Norway with the fuel from the Nordic country covering 35 percent of the nation's needs, and another 25 percent being supplied by Russia. By comparison, Germany has been getting half of all its gas from Moscow, while 46 percent of Italy’s gas imports were also coming from Russia.

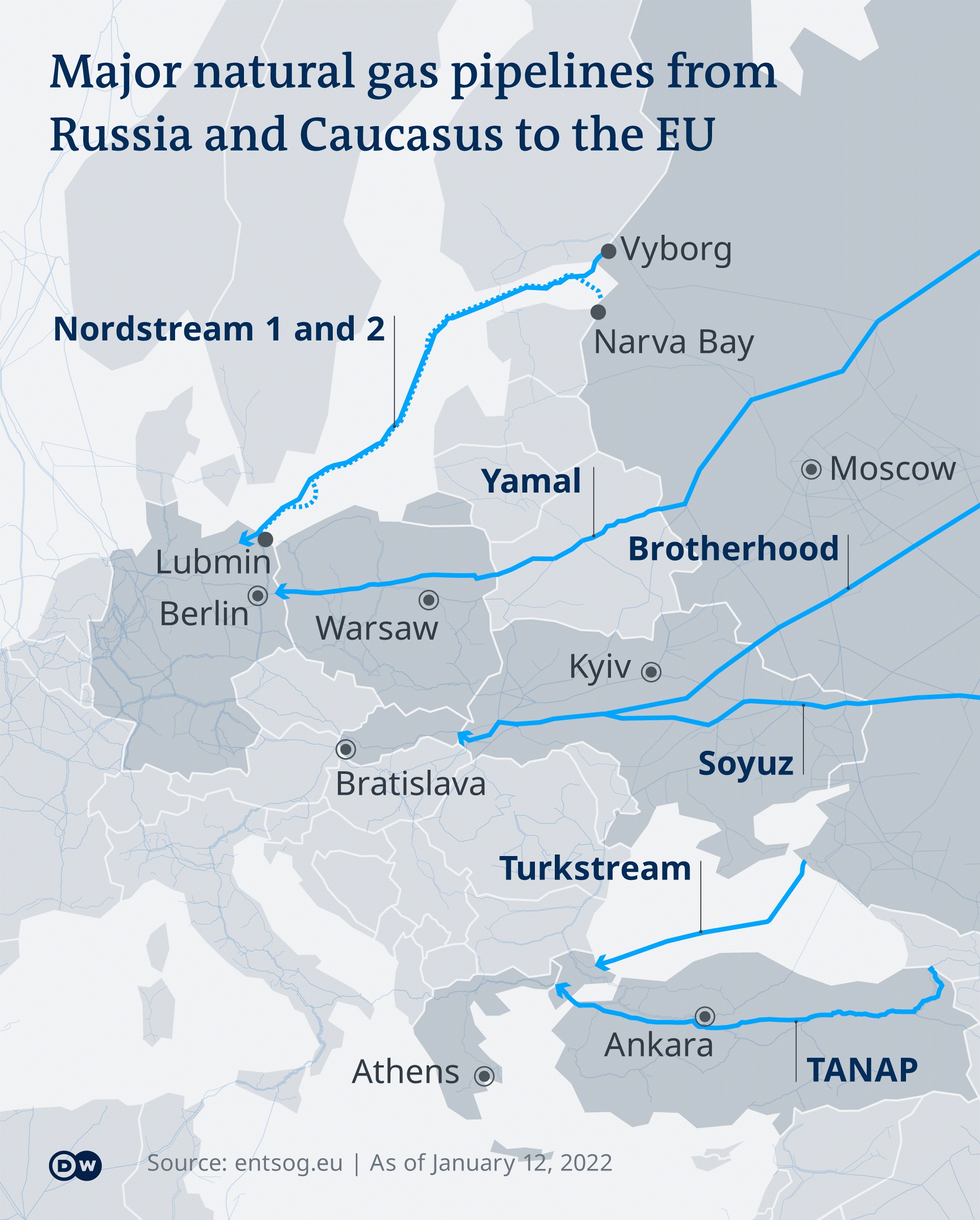

All told, Germany had benefited a lot from its energy cooperation with Russia as a country that is one of the main entry points for Russia’s gas supplies to Europe via the Nord Stream pipeline. In 2021 alone, Germany received 59.2 billion cubic meters of Russia’s natural gas meant for the whole of Europe that was pumped through the Baltic Sea pipeline. Other gas supply routes from Russia include Blue Stream, Turkish Stream, and gas transit via Ukraine.

Major natural gas pipelines from Russia and Caucasus to the EU

Poland consumes around 19 billion cubic meters of gas annually, of which just over 5 billion cubic meters are covered by its own production capacity. The shortfall of 14 billion cubic meters used to be made up by the gas supplied from Russia but Warsaw chose to terminate its contract with Gazprom early. This actually makes a lot of sense for Poland and is not unreasonable: after all, this is a relatively low volume of gas and Poland can substitute the resulting shortfall in several ways.

One way would be to buy gas from Norway and have it shipped via a pipeline. Construction of one such pipeline, Baltic Pipe, is currently proceeding at an accelerate pace. The pipeline is expected to become operational as early as next January. That said, Norway’s gas sector is already approaching the peak of its capacity (which has on a number of occasions been brought to a halt by industrial action). Additionally, Poland could get LNG via its Swinoujscie LNG terminal.

gas pipeline

Today’s situation with Germany’s industrial capacity deteriorating as a result of energy shortages may present an opportunity for Poland, who has been active lobbying against Russian gas, enabling it to challenge Germany as Europe’s leader in the next couple of years.

This could perhaps serve as a plausible explanation for Warsaw’s pushback against Gazprom that has already led to the stoppage of the Yamal-Europe pipeline running through Belarus, Poland, and Germany. Poland snatched away Russian corporation’s stake in EuRoPol, the pipeline operator, to which Russia responded by imposing its own sanctions on the operator, which ultimately resulted in halting gas deliveries via the pipeline altogether.

European Union police service based in The Hague

If the European Commission could succeed in pressuring Poland into returning Gazprom’s stake in EuRoPol to its legitimate owner, Moscow could have reciprocated by greenlighting the resumption of gas transit. That way, the European Commission’s officials would be spared the trouble of having to travel around the world pleading with Algeria, Azerbaijan, and other countries to urgently start supplying additional volumes of gas to Europe. After all, these will not be able to fully substitute the shortfall in supplies.

One cannot help getting the impression that the nations that are a part of a loosely defined Anglo-Saxon bloc whose area of influence includes Poland and the Baltic States, have of late being engaged in acts of subversion and sabotage. Clearly, Poland is not going to really be affected by the shortage of Russian pipeline gas, and nor will the UK. Britain produces half of the needed volume of gas on its own and buys the rest from Norway, the Netherlands, and Belgium. In fact, in terms of gas imports to the UK, it is Norway that holds the lead here. On top of that, about a quarter of Britain’s total gas imports come primarily in the form of LNG with Russian gas accounting for a mere 4 percent of the UK’s energy mix.

People walk past a pro-Brexit protester outside the Houses of Parliament, after Prime Minister Theresa May's Brexit deal was rejected in London, Jan. 16, 2019.

Although more gas could theoretically be supplied to the EU via Ukraine’s gas transportation system, Kyiv has been curtailing some its throughput capacity. This has affected the gas that is normally pumped through its Sohranovka gas distribution facility located in the Luhansk region which is currently under control of pro-Russian forces. Perhaps, instead of traveling all the way to Baku, the EC President Ursula von der Leyen could go to Kyiv and try to apply some pressure on Ukraine’s leadership. This could prove to be much more productive and have an immediate effect to boot.

All in all, the EU needs about 500 billion cubic meters of gas a year. Of these, it had been getting about 155 billion cubic meters from Russia alone. But now, having refused to buy any more gas from the East and having opted for LNG instead, the EU can finally see that it can no longer balance its economic security needs.

Having been forced to handle a resource as complex as liquefied natural gas, one has to keep track of a large number of uncertainties. The two recent accidents at the LNG facilities in the US have resulted in a more than 17 percent drop in the LNG volumes exported from the US to the EU while Asia’s post-COVID recovery has caused the prices in these premium market to skyrocket forcing Europe to face cutthroat price competition. Which explains the current price of USD 1,800 per thousand cubic meters of gas.

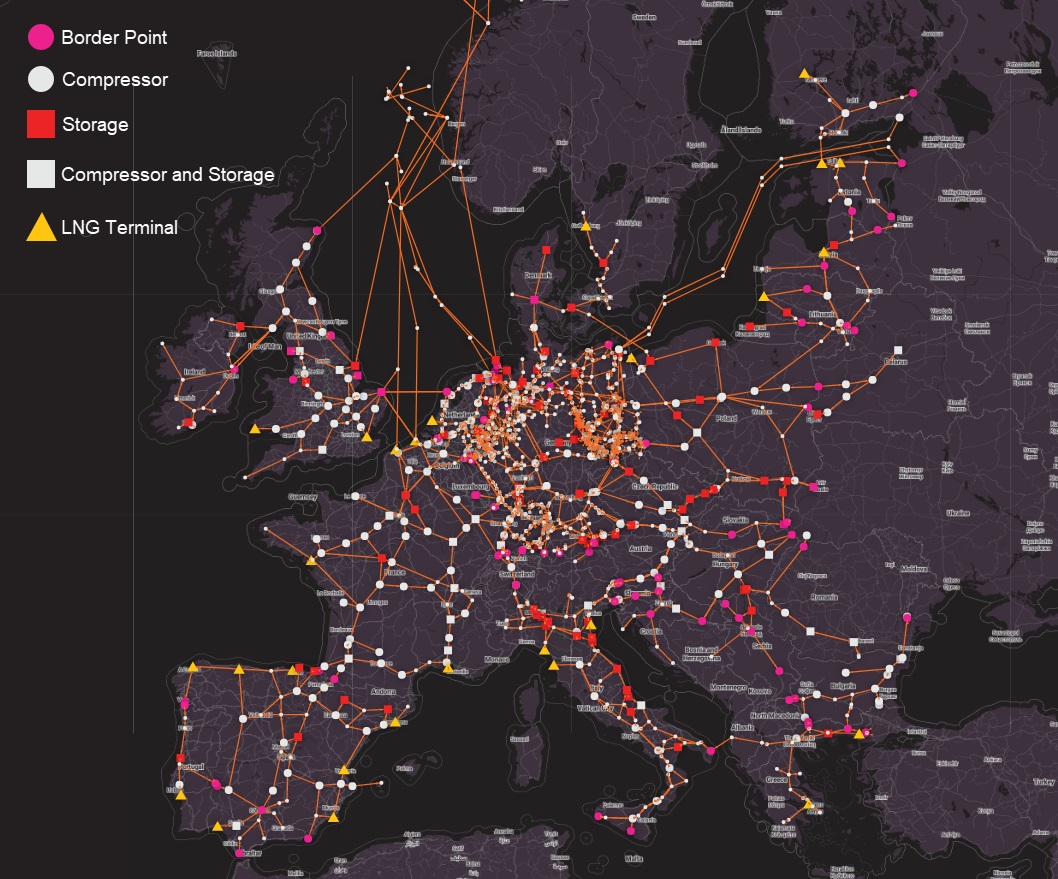

To top it off, the need to build liquefaction terminals is yet another frustrating downside of having to buy LNG as they cannot be built overnight. In addition, given that Europe’s network of interconnecting pipelines is still underdeveloped, it becomes next to impossible to send the gas that has been delivered to an LNG terminal on to the end-cosumers.

Europe gas pipeline map

Generally speaking, issues with logistics are not uncommon when it comes to LNG deliveries. This makes Europe that expects to use LNG to meet its gas needs dependent not only on producers of hydrocarbons but also on shipping companies. Incidentally, Europe’s plans to boost its LNG purchases are causing a shortage of gas carriers as their key producers including Japan, South Korea, and, to a degree, China, are already fully booked with orders for years to come. Experts predict that demand for LNG carriers from transportation companies will keep growing.

Liquefied natural gas terminal

Tellingly, today’s energy crisis was brought on the EU by none other than the EU authorities’ own actions and decisions. Instead of buying gas under long-term contracts pegged to oil prices, Europe makes almost all of its gas purchases under exchange-traded contracts. Which is yet another reason for the current record-high natural gas prices. Furthermore, the European Union has been committed to creating this type of market in the hope that free competition would force suppliers to reduce their prices. However, in the present circumstances, “the invisible hand of the market” has led to quite the opposite outcome.

Having finally recognised the danger of becoming dependent on stock market profiteers, some of the EU member countries have recently been taking careful steps in a bid to return to an oil-pegged gas price. This approach seems to offer tremendous advantages. If Serbia’s example is any indication, this mechanism allows one to buy gas from Russia at a price of around USD 400 per thousand cubic meters instead of the USD 1,800 the rest of Europe has to pay.

Pipes for the South Stream gas pipeline with the Serbian flag

In the meantime, analysts predict that Europe’s gas market will be gravitating toward more stability via long-term contracts and gas-to-oil price pegging. But again, this is likely to result in some dependence of the buyer in the EU on the seller, say, in the Middle East. This might explain the EU’s lukewarm reaction to Qatar’s proposal to sign a 30-year LNG deal.

Over the last ten years, Europe has been taking steps to diversify its sources of energy supply trying to find alternative suppliers, and it has particularly stepped up these efforts in recent months and weeks. Just the other day, the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen was successful in persuading Azerbaijan’s Ilham Aliyev to double the capacity of the Southern Gas Corridor to 20 billion cubic meters a year by 2027 with Baku having additionally committed to supplying 12 billion cubic meters of gas to the EU this year.

Gas from Central Asia is becoming increasingly more important for Europe. Apart from Azerbaijan, the loss of Russian gas could potentially be offset by supplies from Turkmenistan. Although there are no ready-made delivery arrangements in place yet, Turkey is very busy working on putting one together.

In early July, Turkey’s vice president Fuat Oktay announced that the two nations are working on developing three options for the delivery of Turkmenistan’s natural gas to Turkey. However, given that the most feasible of the three will involve construction (that has not even started yet) of a Trans-Caspian pipeline that will connect Turkmenistan’s Turkmenbashy with Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku, it is easy to see how distant is the day when Turkmenistan’s gas finally starts flowing to Europe.

fuel and energy complex of Azerbaijan

Ankara, as part of its bid to become a “logistics superpower”, has been engaged in a feud with Greece over control of vast areas in the eastern part of the Mediterranean thought to hold close to 1.7 trillion cubic meter of gas. Turkey has been trying to beef up its capacity to supply Middle Eastern and North African gas to Europe, straight from the field and to the mainland. With Russia busy fending off a sanctions war waged against it, Ankara is well positioned to gain a considerable competitive edge as a transit country allowing energy resources to flow through its own territory. The benefits offered by this position are only expected to become even more substantial as time goes by.

Shell becomes a partner in Qatar's natural gas field expansion project

According to some energy experts, Europe has already reached an upper limit of gas deliveries it can still attract by paying top dollar for them. All possible volumes of gas are already in Europe’s gas storages facilities. Since March, global LNG exports to Europe have grown 75 percent year-on-year while LNG exports from the US to Europe have nearly trebled. It is expected that LNG supplies to Europe will continue growing further, albeit very slowly, as new assets keep coming online around the word in the second half of the year.

This includes BP’s plans to make fully operational its Indonesia-based Tangguh LNG facility or ENI’s launch of Coral South FLNG floating plant in Mozambique. On top of that, the US is expected to bring nearly 15 million tons’ worth of new LNG capacity to the market. However, growing demand for LNG, and especially in Asia, is likely to fully absorb the extra capacity which means that putting these new facilities into operation is unlikely to have much of an impact on gas prices. To the EU’s chagrin, our planet does not appear to have a gas reservoir that can be uncorked so its contents could be delivered straight to Europe.

Entering carbohydrates into Coral SUL FLNG

It seems obvious that Europe’s current energy crisis could be handled in a very straightforward and prompt manner, that is by lifting sanctions on Russia’ energy sector and, more specifically, by removing restrictions imposed on Nord Stream 2. However, for political reasons, the West is searching for less obvious (and less effective) ways to cope. This is most aptly illustrated by the International Energy Agency’s recent pioneering recommendation it made to the EU. According to this recommendation, given that the EU does not have sufficient quantities of gas anyway, it needs to boost the share of coal and fuel oil in its energy generation. However, the IEA advisers seem to have missed such a minute detail as the fact that the EU explicitly prohibits its members from buying these sources of energy from their largest supplier, Russia.