There is an interesting scene in Chris Nolan’s film Oppenheimer, one which could easily get lost in the complexity of telling the story of the man considered to be the father of the American atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The Trinity test of the first nuclear device has been successfully completed, and Oppenheimer is watching as two men in military uniform are packing up one of Oppenheimer’s “gadgets” for shipment out of Los Alamos to an undisclosed destination.

Oppenheimer talks to them about the optimum height for the detonation of the weapon above ground, but is cut off by one of the soldiers, who, smiling, declares “We’ve got it from here.”

Such men existed, although the scene in the movie — and the dialogue — was almost certainly the product of a scriptwriter’s imagination. The U.S. military went to great lengths to keep the method of delivery of the atomic bomb a secret, not to be shared with either Oppenheimer or his scientists.

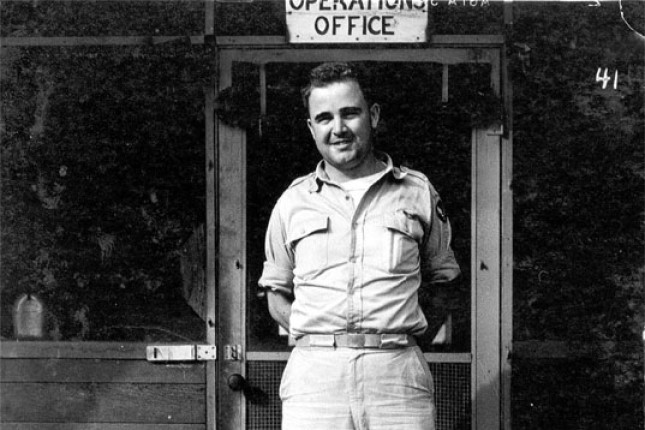

Formed on March 6, 1945, the 1st Ordnance Squadron, Special (Aviation) was part of the 509th Composite Group, commanded by then-Lieutenant Colonel Paul Tibbets. Prior to being organized into the 1st Ordnance Squadron, the men of the unit were assigned to a U.S. Army ordnance squadron stationed a Wendover, Utah, where Tibbets and the rest of the 509th Composite Group were based.

While Oppenheimer and his scientists designed the nuclear device, the mechanism of delivery — the bomb itself — was designed by specialists assigned to the 509th. It was the job of the men of the 1st Ordnance Squadron to build these bombs from scratch.

The bomb dropped on Hiroshima by Paul Tibbets, flying a B-29 named the Enola Gay, was assembled on the Pacific Island of Tinian by the 1st Ordnance Squadron.

Concerned about the possibility of the B-29 crashing on takeoff, thereby triggering the explosive charge that would send the uranium slug into the uranium core (the so-called gun device), the decision was made that the final assembly of the bomb would be done only after the Enola Gay took off.

One of the 1st Ordnance Squadron technicians placed the uranium slug into the bomb at 7,000 feet over the Pacific Ocean.

The bomb worked as designed, killing more than 80,000 Japanese in an instant; hundreds of thousands more died afterwards from the radiation released by the weapon.

For the pilot and crew of the Enola Gay, there was no remorse over killing so many people. “I knew we did the right thing because when I knew we’d be doing that I thought, yes, we’re going to kill a lot of people, but by God we’re going to save a lot of lives,’ Tibbets recounted to Studs Terkel in 2002. He added: “We won’t have to invade [Japan]. You’re gonna kill innocent people at the same time, but we’ve never fought a damn war anywhere in the world where they didn’t kill innocent people,” Tibbets told Terkel. “If the newspapers would just cut out the shit: ‘You’ve killed so many civilians.’ That’s their tough luck for being there.”

An atomic bomb victim with burns, Ninoshima Quarantine Office, Aug. 7, 1945. Photo: Onuka Masami / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain.

Major Charles Sweeney, the pilot of Bockscar, the B-29 that dropped the second American atomic bomb on the city of Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945, held similar convictions about his role in killing 35,000 Japanese instantly.

“I saw these beautiful young men who were being slaughtered by an evil, evil military force,” Sweeney recounted in 1995. “There’s no question in my mind that President Truman made the right decision.” However, Sweeney noted, “As the man who commanded the last atomic mission, I pray that I retain that singular distinction.”

History records the remorse felt by Oppenheimer and his Soviet counterpart, Andrei Sakharov, and the punishment they both suffered at the hands of their respective governments. They suffered from designer’s remorse, a regret — stated after the fact — that what they had built should not be used, but somehow locked away from the world, as if the Pandora’s Box of nuclear weaponization had never been opened.

Having designed their respective weapons, however, both Oppenheimer and Sakharov lost control of their creations, turning them over to military establishments which did not participate in the intellectual and moral machinations of bringing such a weapon into existence, but rather the cold, hard reality of using these weapons to achieve a purpose and goal which, as had been the case for Tibbets and Sweeney, seemed justified.

Ignoring the Executioners

Brigadier General Charles W. Sweeney, pilot of aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. Photo: Public domain / Wikimedia Commons.

This is the executioners lament, a contradiction of emotions where the perceived need for justice outweighs the costs associated.

While the world focuses on the trials and travails of Oppenheimer and Sakharov, they remain silent about the hard positions taken by the nuclear executioners, the men called upon to drop these bombs in time of war. There have only been two such men, and they remained resolute in their judgement that it was the right thing to do.

The executioner’s lament is overlooked by most people involved in supporting nuclear disarmament. This is a mistake, because the executioner, as was pointed out to Oppenheimer by the men of the 1st Ordnance Squadron, is in control.

They possess the weapons, and they are the ones who will be called upon to deliver the weapons. Their loyalty and dedication to task is constantly tested in order to ensure that, when the time comes to execute orders, they will do so without question.

Those opposed to nuclear weapons often point to the example of Stanislav Petrov, a former lieutenant colonel of the Soviet Air Defense Forces who, in 1983, twice made a decision to delay reporting the suspected launch of U.S. missiles towards the Soviet Union, believing (rightly) that the launch detection was a result of malfunctioning equipment.

But the fact is that Petrov was an outlier who himself admitted that had another officer been on duty that fateful day, they would have reported the American missile launches per protocol.

Those who will execute the orders to use nuclear weapons in any future nuclear conflict will, in fact, execute those orders. They are trained, like Tibbets and Sweeney, to believe in the righteousness of their cause.

Dmitry Medvedev, the former Russian prime minister and president who currently serves as the deputy chairman of the Russian National Security Council, has publicly warned the Western supporters of Ukraine that Russia would “have to” use nuclear weapons if Ukrainian forces were to succeed in their goal of recapturing the former territories of Ukraine that have been claimed by Russia in the aftermath of referenda held in September 2022.

“Imagine,” Medvedev said, “if the offensive, which is backed by NATO, was a success and they tore off a part of our land, then we would be forced to use a nuclear weapon according to the rules of a decree from the president of Russia. There would simply be no other option.”

Some in the West view Medvedev’s statement to be an empty threat; U.S. President Joe Biden said last month that there is no real prospect of Russian President Vladimir Putin ordering the use of nuclear weapons against either Ukraine or the West.

“Not only the West, but China and the rest of the world have said: ‘don’t go there,’ ” Biden said following the NATO Summit in Vilnius.

Ignoring Russian Doctrine

But Biden, like other doubters, emphasizes substance over process, denying the role played by the executioner in implementing justice defined on their terms, not that of those being subjected to execution.

Russia has a nuclear doctrine that mandates that nuclear weapons are to be used “when the very existence of the state is put under threat.” According to Medvedev, “there would simply be no other option,” ironically noting that “our enemies should pray” for a Russian victory, as the only way to make sure “that a global nuclear fire is not ignited.”

The Russians who would execute the orders to launch nuclear weapons against the West would be operating with the same moral clarity as had Paul Tibbets and Charles Sweeney some 88 years ago. The executioner’s lament holds that they will be saddened by their decision but convinced that they had no other choice.

Proving them wrong will be impossible, because unlike the war with Japan, where the survivors were given the luxury of reflection and accountability, there will be no survivors in any future nuclear conflict.

The onus, therefore, is on the average citizen to get involved in processes that separate the tools of our collective demise — nuclear weapons — from the those who will be called upon to use them.

Meaningful nuclear disarmament is the only hope humankind has for its continued survival.

The time to begin pushing for this is now, and there is no better place to start that on Aug. 6, 2023 — the 78th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, when like-minded persons will gather outside the United Nations to begin a dialogue about disarmament that will hopefully resonate enough to have an impact of the 2024 elections.

Main photo: Crew of the Enola Gay, returning from their atomic bombing mission over Hiroshima, Japan. At center is navigator Capt. Theodore Van Kirk; to the right, in foreground, is flight commander Col. Paul Tibbetts © Wikimedia Commons / Public domain.

Source: Consortium News.