Bangladesh has officially applied to become a full member of BRICS.

The economic group currently includes five countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, but the number of states hoping to join the organization is growing rapidly.

For example, in early June, a meeting was held in Cape Town between the foreign ministers of BRICS countries and "Friends of BRICS"—12 countries that have most fervently expressed their desire to join BRICS: Argentina, Bangladesh, Venezuela, Gabon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, the Comoros Islands, Cuba, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia.

In total, about 30 countries have already applied to join the group. The requests have both an official and an informal character, aimed at clarifying the procedure and criteria for admitting new members. The ministerial meeting in Cape Town was a preparation for this year's BRICS Summit, to be held in Johannesburg, South Africa, in late August.

Bangladesh's application is of great importance for the future of BRICS. It is indicative that the request to join the alliance was made two weeks after the meeting in Cape Town, after a bilateral meeting between Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa in Geneva.

To date, the organization has accepted only one new member. Brazil, Russia, India, and China created the BRIC group in 2006, and South Africa joined in 2011, turning it into BRICS. It would be symbolic if the decision to further expand is made at the Johannesburg summit.

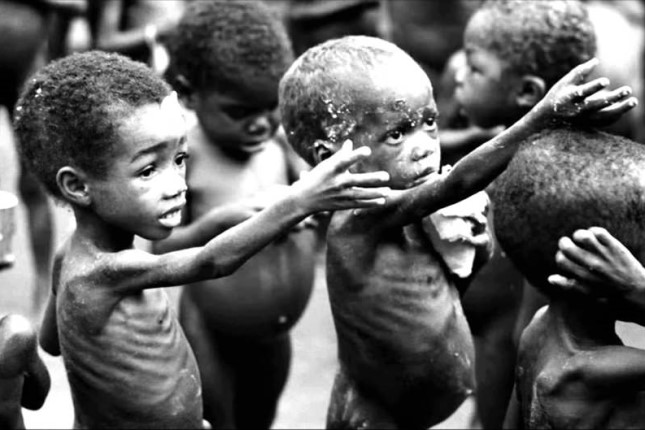

Why is Bangladesh important? It is one of the poorest countries in Asia, with a huge number of economic, social, demographic, and environmental problems. Moreover, it has no political influence or special geopolitical significance. BRICS, on the other hand, has been considered a bloc of emerging powers with obvious political and economic weight in the world. It serves as a counterbalance to the Group of Seven, which unites the most developed and influential Western countries.

BRICS aspires to formulate an alternative, non-Western agenda. Essentially, it aims to become a pole of attraction for countries in the Global South, but at the same time, it has yet to admit a single representative of this Global South. And now, BRICS is faced with a crucial decision: to remain a group of the most influential non-Western countries, possibly expanding its ranks with the remaining most influential countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, and Indonesia, or to start admitting countries that have no weight on the international stage but constitute the majority of the Global South.

Are all equal?

Several formulas for BRICS expansion are currently being considered. One stipulates that priority should be given to strengthening economic cooperation through the BRICS New Development Bank, created in 2015 to finance infrastructure projects in member states and developing countries. The bank has an authorized capital of USD 100 billion. Countries admitted to the bank would be able to participate in various BRICS formats without formally joining the group. Bangladesh, for example, joined the New Development Bank in 2021.

Another proposal involves accepting countries as permanent BRICS members.

The example of Bangladesh shows that developing countries do not want to settle for the role of secondary participants in BRICS—they want to have a say in the decision-making process. But how willing are the BRICS veterans to grant them this right? After all, granting full membership to countries like Bangladesh will complicate the process of reconciling interests and making decisions.

There is much at stake. For example, at the conference in Cape Town, South Africa's Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Naledi Pandor, declared that BRICS, together with sympathetic countries, is capable of changing the entire current system of international relations: "We can create a fairer and more inclusive world that will be more effective in facing numerous challenges of the present, including poverty. The world is experiencing development failure when developed countries do not fulfill their obligations to developing ones. The countries of the BRICS group and its allies are capable of changing this situation."

But to achieve this goal, BRICS will have to become a more open organization. Otherwise, over time, poor countries in the Global South may become disillusioned with the goals and methods of the founding BRICS countries.

The West is eagerly waiting for such disappointment. At the G7 summit in Hiroshima, the head of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, spoke of the Global South's "disappointment" with China and Russia: "They took Chinese loans and found themselves in a debt crisis. All that Russia can offer these countries is weapons and mercenaries."

Clearly, von der Leyen is indulging in wishful thinking. There is no disappointment, and both Russia and China have something to offer the Global South (as well as other BRICS countries). However, it is also evident that the statement by the European Commission head indicates that the West will not easily relinquish its influence. The window of opportunity that has opened up for BRICS will not remain open for long.

Finding a common approach

At the same time, it is evident that there are a number of constraints for BRICS besides just their willingness. All five countries in this organization remain developing and relatively poor in terms of living standards. They cannot simply take on a portion of the Global South's problems. They have their own serious problems to solve in the next 10-20 years.

And it is still unclear what the key difference will be between the model they will propose and what the West has been doing. After all, each of these countries has built its own model of economic growth based on the opportunities created by the West.

Plus, there are quite specific limitations. For example, Russia and China are the largest exporters. In 2022, Russia's trade surplus amounted to USD 330 billion, and China’s to USD 880 billion. This sharply differentiates Russia and China from other BRICS countries and from most potential candidates for membership, perhaps with the exception of Saudi Arabia. Developing common approaches in the economy—taking into account the opinions of countries like Bangladesh—may prove to be more difficult than simply acknowledging dissatisfaction with Western policy.

A new model for joint BRICS development has yet to be found.