There are various ways in which we can examine the Sudanese conflict and its underlying causes. We can treat it as a purely domestic conflict between two warring factions and leaders who are vying for absolute political power. Or we can view it as a proxy war in which outside powers — regional and international — are fighting for the imposition of their own agendas on Sudan.

We can also borrow from the racist Orientalist tropes and assert, yet again, that the people of Africa and the Middle East have always been at war and that the West just wants to establish peace on earth.

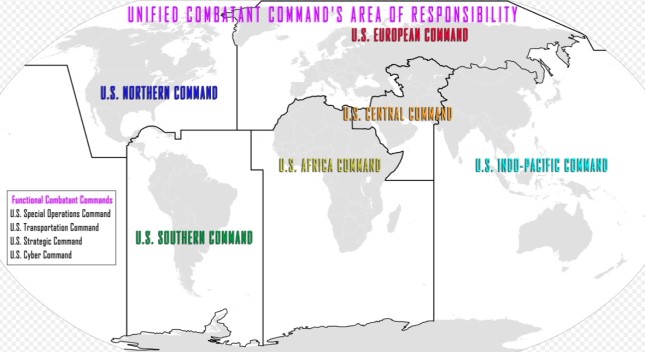

In reality, the conflict in Sudan is not isolated from the U.S. agenda in the whole of Africa. We can’t, as we look around various conflicts in Africa, forget that the U.S. founded Africa Command in 2007. Those regional commands that the U.S. establish are intended purely to govern and manage wars in the region covered by that command.

U.S. AFRICOM area labelled in yellow. Photo: DoD Updater Private / CC BY-SA 4.0 / Wikimedia Commons.

Central Command focuses on wars in the Middle East, while the Africa Command focuses on wars in Africa. Of course, the U.S. would not admit that; the Africa Command chief modestly declared recently that the U.S. aim is merely to help Africans find “African solutions,” presumably because Africans can’t find those solutions without help from the White Man.

Africa Command embodies a declaration that the U.S. has completed its inheritance of the former colonies of European powers. U.S. interests in Sudan have been increasing over time especially as U.S. media express alarm at alleged, expanding Russian diplomatic and military roles on the continent. But Sudan has been at the forefront of U.S. regional conspiracies for decades.

A Former Dynamo

Some of the leaders at the Arab League 1967 summit in Khartoum, from left: Saudi King Faisal, Egypt’s Gamal Nasser, Yemen’s Abdullah Sallal, Kuwait’s Sheikh Al-Sabah of Kuwait and Iraq’s Abd al-Rahman Arif. Photo: Bibliotheca Alexandrina / Public domain / Wikimedia Commons.

Sudan was once one of the most advanced political systems in the Arab world. When much of the Middle East was ruled by despots, Sudan enjoyed periods (in the 1960s) of political liberalization, a thriving press and dynamic political parties. Its leaders often mediated between feuding Arab leaders, and the capital, Khartoum, hosted the famous 1967 Arab Summit in which all Arab countries agreed on the “3 Nos of Khartoum” (they were: no to peace with Israel, no to recognition of Israel and no negotiation with Israel).

The Sudanese Communist Party was once the largest political party in the entire Arab world. But that put the spotlight on Sudan: how could the U.S. tolerate a democracy in which Arabs express their political aspirations freely? Despotic rule has always been the favorite form of government for U.S. and NATO countries.

The unpredictability that democracy brings causes alarm in Washington, D.C. Furthermore, the U.S. government, through its Middle East section, knew that Arab public opinion clashed with the U.S. and Israeli agendas.

The Arabs overwhelmingly, for example, oppose normalization with Israel, when the U.S. considers normalization at the top of its agenda. Only despots can impose normalization on their people. For that, Egypt’s Anwar Sadat was regarded, and still is regarded, as the model Arab ruler, despite his cruel repression and corruption.

A Sudanese colonel by the name of Jaafar Nimeiry seized power in Khartoum in 1969 in a military coup d’etat. He had tried, previous to his ascension to power, to sabotage the democratic process but failed. He fashioned himself after the Egyptian charismatic leader, Gamal Abdul-Nasser, although he had none of the charisma or brilliance of Nasser.

At first, Nimeiry ruled as a socialist Arab nationalist but that changed after 1971 when he faced what he said was a communist plot to unseat him from power. He then launched an anti-communist campaign against one of the most influential political parties in the country. His relationship with the U.S. started after the coup, as he began to veer away from the U.S.S.R.

Natural US Ally

Sudan’s Prime Minister Gaafar Mohammad Nimeiry, right, arriving in U.S. for a state visit, 1983. Photo: US Dod / Michael Tyler / Wikimedia Commons.

His savage punishment of communists, and of communist sympathizers, rendered him into a natural ally of the U.S. and the West. It is not far-fetched to think that the U.S. aided his anti-communist purges, as it had done in several Arab and non-Arab countries.

At first, Nimeiry established relations with China, but then received U.S. backing. He was quickly transformed from a (brief) revolutionary mimic of Nasser into a lynchpin of U.S. plots in North Africa. This coincided with his discovery of religion and the propagation of a conservative Islamist message. His Islamism, naturally, did not rankle Washington as long as he was an obedient client and as long as he deviated from staunch support for Palestinian struggle (Islamism was a close ally of Western plots against the left during the Cold War).

Nimeiry was paid handsomely by the U.S. to facilitate the smuggling of Ethiopian Jews into Sudan (that was dubbed Operation Moses by Israel). The Sudanese despot did not object to Mossad operations in his country as long as the U.S. continued to support him against his opponents, and as long as his internal repression was blessed by Western countries.

But Nimeiri was overthrown in 1985, and after a brief civilian period, he was succeeded by another military despot, Omar Al-Bashir. Al-Bashir cultivated the Islamists in Sudan and claimed at first to support Palestinian struggle and later joined the Iran axis in the region.

But he had a secret deal (for a fee, undoubtedly) to surrender Carlos the Jackal to France, after allowing him to reside in Sudan. He later betrayed the Palestinians and switched sides to join the Saudi-UAE axis. He was overthrown in 2019.

Hopes for a New Era

A civil demonstration against the October 2021 coup in Sudan. Photo: Osama Eid / CC BY-SA 3.0 / Wikimedia Commons.

The people of Sudan aspired for a peaceful democratic transition to a new political era. But the top military leaders would not surrender power and reneged on promises they had made to civic groups leading to the uprising against the dictatorship.

The two generals (Abdel Fattah Burhan who leads the Sudanese Army and Hamidti who leads the Rapid Support Forces, RSF) followed in the footsteps of other Arab despots who knew that the way to Congress’s heart passes through Tel Aviv. Against the wishes of the Sudanese population, both generals established open relations with the Mossad.

And while they did not allow a U.S.-picked technocrat to exercise power as a prime minister (Hamdouk), they went ahead and ousted the civilian component from the government to rule without a civilian façade. This coup of 2021 (by the two generals with Mossad support) didn’t trigger sanctions in Washington, and the U.S. administration continued to have excellent relations with both generals. The two generals resorted to force and the military shot and killed protesters to secure the new coup.

The U.S. did not mind the use of force; it has other considerations, including an ever-expansive role in Africa — always in the name of fighting terrorism, which never seems to end or even diminish.

Saudi Arabia & UAE Picked Sides

Both Saudi Arabia and UAE served as sponsors of the two generals, but each picked a side. The UAE favored the RSF while the Saudi government favored the army commander, Gen. Burhan.

The previous ruler, Omar Bashir, had formed an Islamist political base, and his arrest did not eradicate its influence from the country, although it was banned from political activity by the new rulers.

Gen. Hamidti of the RSF then accused Gen. Burhan of cultivating relations with the Islamists in order to establish a popular base of support (there is merit to the accusation especially after Gen. Burhan released some of the key Islamists during the recent fighting).

That allowed the UAE to make its preference: Gen. Hamditi was its man, because the UAE was combatting all traces of the Muslim Brotherhood throughout the region — and throughout the world.

Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, has been embroiled in an announced bitter feud with the UAE, in Yemen, Libya and Sudan. Each side serves as a regional patron to a different group. But the UAE’s close relations with Israel underlines the Mossad patronage of Gen. Hamidti. Gen. Burhan, on the other hand, is sponsored by the Israeli Foreign Ministry and Egypt.

The conflict in Sudan is a domestic, regional and international conflict. The U.S. and its media, wary of a Russian role in Africa, have exaggerated the part played by the Wagner group and all but omits the influential roles of U.S. allies in the region.

The RSF is more than a force; it is an actual army which only lacks an air force (the RSF is bigger than the regular army). Somebody has been equipping the warring factions with advanced weapons.

It was the U.S. which lifted Sudan from the terrorist list, allowing the military junta to augment its arsenal. The deal which resulted in the normalization with Israel required that the U.S. would help the ruling junta to break out of the long isolation that was imposed on Sudan by the U.S. and Israel.

There is no end in sight in Sudan; somebody from outside the country is fueling the conflict. In the Middle East, we often used to say, when the U.S. evacuates its personnel, it is usually a sign of a sinister plot by Washington against that country. The U.S. has just evacuated its personnel.

This does not bode well for the future of Sudan. In 1976, when the U.S. evacuated its personnel from Beirut, it marked the intensification of a civil war that would not end until 1990.

Main photo: Khartoum’s Africa road tunnel, 2020 © Mohammed Abdelmoneim Hashim Mohammed / CC BY-SA 4.0 / Wikimedia Commons.

Source: Consortium News.