It is no secret that United Nations mediation is in a state of decline. The U.N. is no longer in the lead role in conflict countries where the secretary-general and his representatives or special envoys are mandated to provide mediation and good offices. In most of these conflicts, powerful members of the Security Council, regional and subregional organizations are taking the lead, pushing the U.N. to the sidelines.

The only two conflicts where the U.N. is still clearly in the lead are Cyprus and Western Sahara, and, in both countries, it has failed for decades to make any progress.

One needs only to look at how many U.N. envoys cannot enter the countries where they are supposed to be mediating or they have limited access to the actors they should be engaging with. The U.N. has been largely sidelined in many mediation processes by parties to, or backers of, these proxy conflicts, who are ironically taking the mediation lead (for example, in Syria and Yemen).

In recent years, powerful P5 countries [the five permanent members of the Security Council — China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States] and others have routinely interfered with the appointment of the secretary-general’s envoys, effectively imposing candidates with little relevant experience. Many envoys have been appointed to countries they have never been and whose language they do not speak.

The U.N. has made a great deal of effort since former Secretary General Kofi Annan’s “In Larger Freedom” reform proposals in 2005 to professionalize its mediation processes and establish a series of guidelines that place inclusion at the forefront.

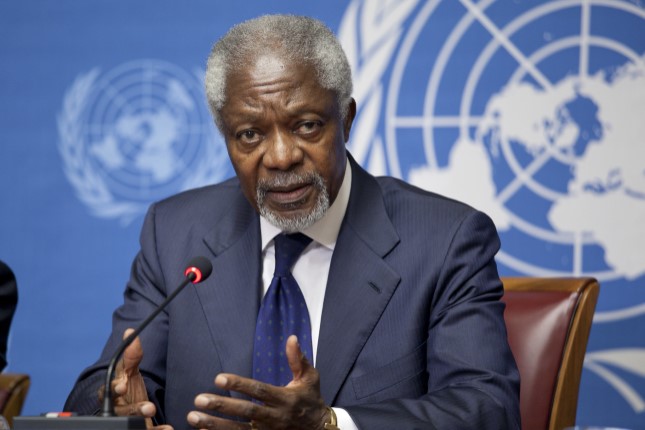

Kofi Annan in 2012. Photo: U.S. Mission Geneva / Flickr / CC BY-ND 2.0.

However, the practice continues to lag behind the new standards. The establishment of the outstanding Mediation Unit, its very useful Standby Team of Senior Mediation Advisors, and High-Level Advisory Board have all been positive developments, but more needs to be done to ensure that the U.N. upholds its mediation standards of consent, impartiality and inclusivity, particularly in the conflicts that have come to define these past decades.

Earlier this year, the International Center for Dialogue Initiatives, which I chair, published a report titled “Libya: An Assessment of Twelve Years of UN Mediation.” It found that political dialogues facilitated by the U.N. lacked inclusivity and impartiality and were often undermined by the interests and interference of major powers, a pattern that analysts also see in Syria, Yemen and other political processes.

Declining Role

The U.N. is no longer seen as an impartial body with a strong and respected voice globally. People living in conflict-ridden countries are increasingly viewing the U.N. as promoting the interests of the West and the powerful. But this wasn’t always the case.

May 21, 1960: U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld addresses a dedication ceremony for Evgeniy Vuchetich’s statue, “Let Us Beat Swords into Ploughshares,” a gift from the Soviet Union to the U.N. Photo: UN Photo / JG.

In previous decades, the U.N. played a major role in facilitating peace processes in many countries and regions around the world (such as Cambodia, Namibia, Central America and Timor-Leste), and numerous dedicated U.N. officials have paid the ultimate price and lost their lives in the pursuit of peace.

The decline of U.N. mediation is taking place against a backdrop of the increased polarization of global politics that can be seen in the Security Council, where Russia and China are often pitted against the United States, the United Kingdom and France.

The continuing monopoly of these three countries — the U.S., the U.K. and France — over the drafting of Security Council resolutions and their undue influence in the Secretariat, where they continue to monopolize the leadership of the peace and security departments, has further eroded the U.N.’s credibility in mediation processes.

Ukraine Should Have Been an Opportunity

The tragic conflict in Ukraine should have presented an opportunity for the U.N. to play the major mediating role and to act as a bridge between Russia and NATO, in the same way that Dag Hammarskjold had carved space for the U.N. to act as a bridge between the East and West during the Cold War. Many countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Israel, Türkiye and South Africa, with other African states, are all vying to play this role, but the U.N. is nowhere to be seen.

In this month’s edition of our newsletter, “Diplomacy Now,” experts and academics, some of whom have worked with or inside the U.N. system, weigh in on the institution’s mediation record in Sudan, Syria, Yemen and Afghanistan, diagnosing what they see as serious flaws and providing recommendations for future engagement.

Keep in mind that the views of these authors do not necessarily reflect our own; however, we publish their essays because we believe that there must be greater reflection and open discussion on the quality of U.N. mediation, if it is to positively affect people whose lives have been or continue to be shaken by war. We strongly believe in a more effective U.N. that is fully able to address today’s global peace and security issues.

Main photo: The war in Ukraine should have been an opportunity for the U.N. to play the major mediating role, the author writes. But it is nowhere to be seen © Presidency of Ukraine / Twitter.

Source: Consortium News.