After apparently lengthy negotiations via Julian Assange’s attorneys, the WikiLeaks founder agreed to plead guilty to one felony charge of illegally obtaining and publishing U.S. government documents of various kinds — many standing as evidence of war crimes and human rights abuses, others exposing the Democratic Party’s corruptions during the presidential campaign of Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Assange was sentenced Wednesday to a term of five years and two months, precisely the time he spent at Belmarsh, the maximum-security prison in southeast London. It was from Belmarsh that Assange fought requests for his extradition to the U.S., where he would have faced multiple charges and a lengthy sentence under the 1917 Espionage Act. When he departed for Australia at the conclusion of the proceeding in Saipan, the largest of the Northern Marianas and also the capital city, he became a free man for the first time in 14 years, counting from his time under house arrest in 2010.

Let us take the utmost care with our diction at this surprising and welcome turn. This will enable us to fathom the moment clearly.

Julian Assange has not been freed, passive voice, the beneficiary of decisions taken by the American and British judiciaries — and almost certainly in the Biden regime’s upper reaches. Julian Assange has achieved his freedom, actively. Even during the darkest moments of his years under house arrest, in asylum at Ecuador’s London embassy, and at Belmarsh, he never surrendered his sovereignty. He remained ever the captain of his soul, and never did he allow his captors entry onto his ship.

It was for this, most fundamentally, that Assange has suffered these past years, especially the five he spent in a cell at Belmarsh. The project was precisely to destroy his sovereignty, to break him one way or another, and he refused to break. His will — and I simply cannot imagine the awesome muscularity of it — has seen him through to victory.

When news of his impending freedom arrived with us last Monday evening, I reacted without hesitation, “It is not a bad deal. Everyone knows the truth and worth of what Assange did. Nothing lost. A good man’s life hung in the balance — this a gain.”

“Everyone” seems already an overestimation, but I will get to this in a moment.

Among the curious details of Assange’s plea is the choice of the federal courthouse in the Northern Marianas, a U.S. possession, for the denouement of his case. Assange’s legal team requested this peculiar location, let us not miss. It is remote from the U.S. mainland but close to his native Australia. There are two things to surmise from this, I think.

Northern Marianas in Oceania. Photo: TUBS / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0.

One, it is likely Assange’s attorneys thought it a very bad idea for their client to set foot on American soil anywhere near the court in Washington’s environs where cases of this kind, national-security cases, are customarily tried — tried before jurors drawn from a pool well populated with active and retired national security operatives, bureaucrats and assorted apparatchiks.

That the locale for the final settlement was negotiated away from the District Court of Eastern Virginia indicates that Assange’s lawyers remained mistrustful of U.S. assurances of a fair treatment under the law even while their talks proceeded.

Two, and the larger point here, moving the case to so out-of-the-way a courtroom indicated that Assange and his legal defense almost certainly had considerable leverage in determining the terms under which he achieved his freedom. This tells us something important about the years Assange spent at Belmarsh subjected to disgracefully punitive conditions and the circus various judges, Vanessa Baraitser high among them, made of the British courts.

I have long assumed, as many others may have, that the Biden regime and its predecessor simply did not want Assange extradited because it did not want to take up a trial that would more or less automatically lead to a sentence of 170 years. Too potentially messy, too politically risky, too harsh a light on this administration’s hypocrisies in the matter of press freedom and its indifference to, if not its approval of, the British authorities’ inhumane treatment of a man whose organization exposed war crimes.

How else to explain the lengthy delays in the London courts these past five years? And I cannot but think with something close to conviction that the corporate press in America, chiefly The New York Times, had some modest voice in the decision to negotiate a plea that reflects to some extent the Assange side’s terms?

The New York Times Building. Photo: Michal Osmenda / CC BY-SA 2.0 / Wikimedia Commons.

The Times has avoided serious reporting of the Assange case for years. Embarrassing it would have been for the paper to report proceedings in Eastern Virginia, as it would have been obliged to do. We all remember that The Times made full use of WikiLeaks releases until, in April 2017, Mike Pompeo denounced Assange as “a state actor of Russia.” It was at that point Washington turned frontally against the organization and its founder, and the corporate press dutifully followed the lead of Trump’s egregious secretary of state.

The Biden regime has managed at last to drop a hot potato, but it is a stretch to assume it has not burned its fingers. As others have remarked, it could have vacated its case entirely and, indeed, gone so far as to offer Assange compensation for his suffering while facing unjust charges.

That would have marked a dramatic redemption. Instead, it leaves the door still wide open to pursuing cases such as Assange’s whenever a reporter’s truths are similarly inconvenient. This is self-inflicted damage atop years of self-inflicted damage, in my read. The Biden government’s exit from this case more or less mutilates any claim it will henceforth assert to respect press freedom and First Amendment rights.

Sheer Endurance

HM Prison Belmarsh. Photo: Anders Sandberg / Flickr / CC BY-NC 2.0.

I measure the magnitude of Julian Assange’s triumph not in passing political terms, although the politics of his achievement of freedom are important. I view it in more personal terms. His greatest victory lies in the strength and sheer endurance he summoned and consistently displayed as the machinery of two sovereign states attempted to destroy him.

Several years ago, readers will recall, Nils Melzer testified in Baraitser’s court that Assange’s treatment met official definitions of psychological and physical torture. Not long after the U.N.’s special rapporteur on torture gave his testimony, I began an essay on the Assange case for Raritan, the cultural and political journal. It came to me as I wrote “Assange Behind Glass,” which I reproduce here from my web site archives, that we had to see it in the context of the “total domination” Hannah Arendt explored in The Origins of Totalitarianism, her look back, in 1951, at the horrors of the 20th century’s first half. “Its intent is to strip humanity of all identity and individuation,” I wrote of Arendt’s theme. And from her text: “Totalitarian domination attempts to achieve this through ideological indoctrination of the elite formations and through absolute terror in the camps. . . . The camps are meant not only to exterminate people and degrade human beings but also serve the ghastly experiment of eliminating, under scientifically controlled conditions, spontaneity itself as an expression of human behaviour and of transforming the human personality into a mere thing. . . so the experiment of total domination in the concentration camps depends on sealing off the latter against the world of all others, the world of the living in general.”

I also brought Giorgio Agamben into the Raritan piece, for he saw our reality in the reality of the camps. “What is a camp, what is its juridico-political structure?” he asked in Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford, 1998). “This will lead us to regard the camp not as historical fact and an anomaly belonging to the past (even if still verifiable) but in some way as the hidden matrix of the political space in which we are still living.”

I still think of Assange’s extended ordeal in this context. And for this reason I read his achievement of freedom as a personal victory, the accomplishment of an exceptional individual, a man who stood against a system that operates in a state of exception (a theme Agamben elucidates elsewhere) and defeated it.

News of Assange’s freedom reached us, South of the Border as we are at the moment, via my iPad late Monday evening. After reading The New York Times report — cautious, workmanlike, wire-service-y — we looked at the comment thread beneath the piece. And there went my assumption that “everyone” knows the truth and worth of Assange’s work.

The great majority of the comments we read — and one can never tell the extent The Times selects these to give a picture of the reading public that it wishes to project — were shockingly hostile to the agreement. I customarily avoid providing links to Times pieces, but “Assange Agrees to Plead Guilty in Exchange for Release, Ending Standoff with the U.S.” seems to warrant an exception.

Peruse the piece if you wish, but be sure to look at these comments. Most condemn Assange’s release from prison, or argue he should stand trial and get the lengthy sentence attaching to the espionage charges, or assert that he endangered Americans and others by releasing various documents to do with U.S. military operations, or that he is a stooge of Vladimir Putin, or that he corrupted the 2016 election and is responsible for Hillary Clinton’s loss. And on and on.

From one M Caplow in Chapel Hill: “Hard to sympathize with somebody who made Trump’s victory more likely. His intentional damage to Hillary Clinton offsets any merit to his other activities.”

From Futbolistaviva in San Francisco:

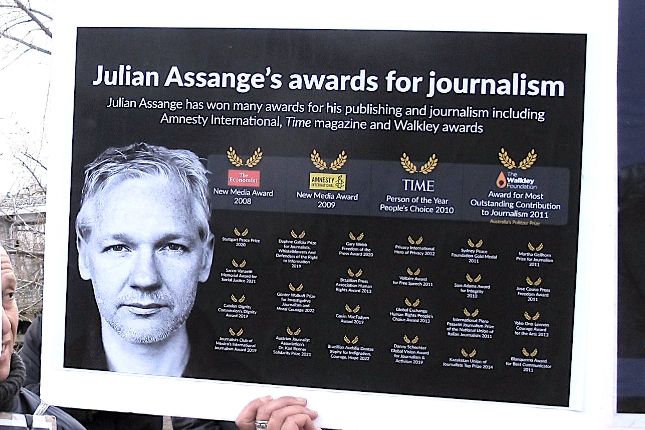

“He is not and never was a journalist. He was a hacker. Hopefully this is the last we hear about him.”

Awards the WikiLeaks founder received for his investigative work listed on a protest sign in February 2024. Photo: Cagibi54 / CC0 / Wikimedia Commons.

And in the motivated logic line, this from sheikhnbake, in Cranky Corner, Louisiana: “With the Pentagon Papers, the NY Times did not steal any secret government data. That would have constituted espionage. They merely won the right to print what they’d received from someone else. Assange and his menagerie actually hacked in and stole the information and then published it.”

There must be some difference I cannot fathom, sheikhnbake, between the use of a Xerox machine, circa 1970, and a computer as used 40 years later.

After reading a goodly amount of this, we looked at how Tucker Carlson responded to this dramatic turn. “A good man, finally free. The tide is turning,” he wrote on “X.” I am not with Carlson’s turning tide — none did — but let us set this aside. What followed Carlson’s remark was remarkable.

“Julian Assange remains a hero,” David Benner, Nemesis of Neocons, responded. “His freedom should be celebrated, but no one should rest until he receive a full pardon and medals for exposing regime war crimes.” The real criminals, another reader remarked are agencies with three-letter designations. Etc.

Astute. To the point. Devoid of ideological charge.

Russiagate Scars

There is only one way to account for this, and it sickens, to be bluntly honest. We see here in the full light of day the scars the Russiagate years have left and the extent to which these have disfigured not only American discourse but so many American minds. There is no truth to speak of in our liberal circles. There is but Democratic truth, and this truth must always, one way or another, explain Hillary Clinton’s loss to Donald Trump.

Of what use are these people? They have surrendered their very ability to think.

A little while after the Raritan essay came out, Consortium News began a 10–part series called “The Revelations of WikiLeaks.” This is a detailed catalogue and summary of all the Assange organization’s major publications. The series is in keeping with the exceptional dedication and compassion Joe Lauria, Consortium’s e.i.c., has from the first displayed toward Julian Assange and his case. “The Revelations of WikiLeaks” can be read here, and I offer it to The Floutist’s readers not only for its intrinsic worth: It also raises a question.

I cannot be alone in noting that WikiLeaks, for obvious reasons, has not kept up the pace of its publications these past years. How could it? But with so worthy a past in mind, we have to wonder what will become of WikiLeaks now— now that its founder is free and walking to and fro in the world once again. More to the point, what will be Julian Assange’s path forward?

I long thought, with unwanted pessimism, that it would be impossible for Assange to go free because he knows too much — especially but not only the source of all that pilfered Democratic Party mail. To expose all the lies that the Russians were responsible for getting those documents to WikiLeaks would be to explode a very great deal of the grotesque edifice we call Russiagate. Impossible to think Assange could go free with all he knows of this and other matters. All that would be at stake would fall into the “too big to fail” file.

Are their undisclosed codicils attaching to the Assange’s camp’s plea agreement? Will his professional activities henceforth be curtailed by agreement? These are inevitable questions, even if one does not care to pose them. The answers are unclear and may never be clear. Out of respect and admiration for a man who has just won his freedom after paying a very high price in his fight for it, I leave these matters to him and those around him.

Main photo: Assange discussing the plea deal with his lawyer Gareth Pierce © WikiLeaks via X.

Source: Consortium News.