In many accounts the C.I.A. is regarded as the prime mover behind the 1953 coup in Iran, yet Britain was in fact the initial instigator and provided considerable resources to the plot, which U.K. planners named “Operation Boot.”

In the early 1950s, the Anglo–Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), or BP as it is now known, was run from London and owned jointly by the British government and private citizens. It controlled Iran’s main source of income and oil, and by 1951 had become, according to one British official, “in effect an imperium in imperio [an empire within an empire] in Persia.”

Iranian nationalists objected to the fact that the AIOC’s revenues from oil were greater than the Iranian government’s.

Britain’s ambassador in Tehran, Sir Francis Shepherd, had a typically colonialist take on the situation. The declassified files show his writing: “It is so important to prevent the Persians from destroying their main source of revenue…by trying to run it themselves.”

He added: “The need for Persia is not to run the oil industry for herself (which she cannot do) but to profit from the technical ability of the West.”

Of course, Iran was perfectly capable of running its own oil industry. In March 1951 the Iranian Parliament voted to nationalise oil operations, take control of the Anglo–Iranian Oil Company and expropriate its assets.

In May, Mohammed Mossadeq, the leader of Iran’s social-democratic National Front Party, was elected as prime minister and immediately implemented the bill.

Britain responded by withdrawing the AIOC’s technicians and announcing a blockade on Iranian oil exports. Moreover, it also began planning to overthrow Mossadeq.

“Our policy”, a British official later recalled, “was to get rid of Mossadeq as soon as possible”.

"An Authoritarian Regime"

Following the well-worn pattern of installing and backing compliant Middle Eastern monarchs, British officials were keen on “a non-communist coup d’etat, preferably in the name of the shah,” which “would mean an authoritarian regime.”

The ambassador in Tehran wanted “a dictator” who “would carry out the necessary administrative and economic reforms and settle the oil question on reasonable terms” – meaning reversing the nationalisation.

The military strongman chosen to preside over the coup was General Fazlollah Zahedi, a figure who had been arrested by the British for pro-Nazi activities during the Second World War, and was by the early 1950s Iran’s interior minister.

Despite British propaganda, Mossadeq’s government was privately recognised by U.K. officials as generally being democratic, popular, nationalist and anti-communist.

One difference between the National Front and other political groupings in Iran was that its members were, as Britain’s ambassador privately admitted, “comparatively free from the taint of having amassed wealth and influence through the improper use of official positions.”

Mossadeq had considerable popular support, and as prime minister managed to break the grip over Iranian affairs exercised by the large landowners, wealthy merchants, the army and the civil service.

Danger of Independence

The popular nationalist threat posed by Mossadeq was compounded by his alliance of convenience with the pro-Soviet Iranian communist party – Tudeh.

As British and U.S. covert planners met throughout 1952, the former tried to enlist the latter in attempting a joint overthrow of the government by deliberately playing up the scenario of a communist threat to Iran.

One British official noted in August 1952 that “the Americans would be more likely to work with us if they saw the problem as one of containing communism rather than restoring the position of the AIOC.”

However, neither the British nor U.S. planning files show that they took seriously the prospect of a communist take-over of the country. Rather, both primarily feared the dangerous example Mossadeq’s independent policies presented to Western interests in Iran and elsewhere in the region.

By November 1952, an MI6–Foreign Office team was jointly proposing with the C.I.A. the overthrow of Iran’s democratic government. British agents in Iran were provided with radio transmitters to maintain contact with MI6, while the head of the MI6 operation, Christopher Woodhouse, put the C.I.A. in touch with other British contacts in the country.

MI6 also began to provide arms to tribal leaders in the north of Iran.

Ayatollah Kashani

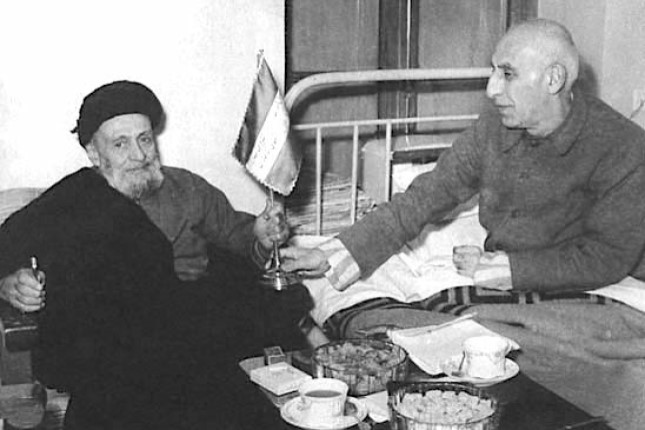

Kashani with Mossadegh. Photo: Unknown author / Flickr / Wikimedia Commons.

The most important religious figure in Iran was the 65-year-old Shia cleric, Ayatollah Seyyed Kashani. He had helped German agents in Persia in 1944, and a year later helped found the unofficial Iranian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, the Fadayan-e-Islam (“Devotees of Islam”), a militant fundamentalist organisation.

The Fadayan was involved in a number of terrorist attacks against Iran’s then ruler, the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, in the late 1940s, including an assassination attempt in 1949, and killed the Shah’s prime minister, Ali Razmara, in 1951. Around this time, it appears Kashani broke with the organisation.

By the early 1950s, the Ayatollah had become the speaker in the Iranian parliament, the Majlis, and a key ally of Mossadeq.

A U.S. intelligence report noted that, like Mossadeq, Kashani had a large popular appeal and strongly supported the National Front’s policies of oil nationalisation and the elimination of British influence in Iran.

However, by early 1953 relations between Kashani and Mossadeq became strained, notably over the latter’s proposals to extend his powers, and in July of that year Mossadeq dismissed Kashani from the post of speaker.

Tensions between Mossadeq and Kashani and other religious supporters of the ruling National Front were further stirred up by two of the principal British agents in the country: the Rashidian brothers, who came from a wealthy family with connections to the Iranian royals.

Instrumental in securing the Shah’s endorsement for the coup, the Rashidians also later acted as go-betweens among army officers distributing weapons to rebellious tribes and other ayatollahs, as well as Kashani.

Rioting

Tanks in the streets of Teheran, 1953. Photo: Public domain / Wikipedia.

In February 1953 rioting broke out in Tehran, and pro-Zahedi supporters attacked Mossadeq’s residence, calling for the prime minister’s blood.

Stephen Dorril notes in his book, MI6: Fifty Years of Special Operations, that this mob had been financed by Ayatollah Kashani and was acting in collaboration with British agents.

Kashani’s potential for attracting the Iranian street had been noted by the British Foreign Office, which remarked on his “considerable following in the bazaar [markets] among the older type of shop-keeper, merchant and the like. This is the chief source of his political power and his ability to stage demonstrations”.

British pay-offs had also secured the cooperation of senior army and police officers, deputies and senators, mullahs, merchants, newspaper editors and elder statesmen, as well as mob leaders.

“These forces,” explained MI6 officer Christopher Woodhouse, “were to seize control of Tehran, preferably with the support of the shah but if necessary without it, and to arrest Mossadeq and his ministers.”

The British also operated agents inside the Tudeh Party and were involved in organising “false flag” attacks on mosques and public figures in the party’s name.

C.I.A. officer Richard Cottam later observed that the British “saw the opportunity and sent the people we had under our control into the streets to act as if they were Tudeh. They were more than just provocateurs, they were shock troops, who acted as if they were Tudeh people throwing rocks at mosques and priests.”

Black Propaganda

All this was intended to frighten Iranians into believing that a victory for Mossadeq would be a victory for communism and would mean an increase in Tudeh’s political influence.

A secret U.S. history of the coup plan, drawn up by C.I.A. officer Donald Wilber in 1954, and published by The New York Times in 2000, relates how C.I.A. agents gave serious attention to alarming the religious leaders in Tehran by issuing black propaganda in the name of the Tudeh Party, threatening these leaders with savage punishment if they opposed Mossadeq.

Threatening phone calls were made to some of them, in the name of the Tudeh, and one of several planned sham bombings of the houses of these leaders was carried out.

British declassified files show that both the British and U.S. governments considered installing Ayatollah Kashani as a client political leader in Iran following the coup.

In March 1953 Foreign Office official Alan Rothnie wrote how Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden had discussed with the head of the C.I.A., General Walter Bedell Smith, the possibility of dealing with Kashani as an alternative to Mossadeq.

Rothnie noted that “they would be glad to learn whether we have any information which would suggest that the United States and United Kingdom could find a modus vivendi [way of working] with Kashani once he was in power. They feel that Kashani might be bought, but are doubtful, once he was in power, whether he could be held to a reasonable line.”

The British and U.S. consideration of Kashani as a future leader is itself instructive yet the answer that came back both from the U.S. State Department and the British Foreign Office was that Kashani would be a liability: he was seen as far too independent.

"Complete Political Reactionary"

The Foreign Office stated that Kashani “would be of no use to us, and almost certainly a hindrance, as a successor to Dr Mossadeq, both generally and in an oil settlement.”

It regarded him as even more anti-Western than Mossadeq, describing him as “anti-British” and as nursing a “bitter enmity towards us” after being arrested for helping the Nazis during the war.

The Foreign Office termed him “a complete political reactionary…totally opposed to political reforms.” “He would conceivably…accept Western money,” it noted, but he would not follow “a reasonable line about an oil settlement.”

“If he came to power it would be impossible to reach a modus vivendi with him…We could not count on Kashani giving Persia that minimum of order and stability which is our basic need,” the Foreign Office concluded.

However, written comments appended to this report show other Foreign Office officials pondering the “the idea of Kashani as a stop gap, or a bridge to some more amenable regime.”

One official questioned whether Britain should work to replace Mossadeq with Kashani “before we can expect something better in order to produce the necessary public revulsion.”

The British view was that if Kashani could not be entrusted with power, his forces could still be used as shock troops to change the regime.

The evidence points to British and U.S. support being provided to this “complete political reactionary” both before and after the report noted above was written, in March 1953.

Go-Ahead

Aug. 16, 1953: Pro-Mosaddegh protests in Tehran. Photo: William Arthur Cram / The Guardian / Wikimedia Commons.

In late June 1953, the U.S. gave the final go-ahead for the coup, setting the date for mid-August.

The initial coup plan was thwarted when Mossadeq – having been warned of the plot, possibly by the Tudeh Party — arrested some officials plotting with Zahedi and set up roadblocks in Tehran. This caused the Shah to panic and flee abroad where he would stay until the coup restored him as absolute monarch.

In order to trigger a wider uprising, the C.I.A. turned to the clergy and made contact with Kashani via the Rashidian brothers. Footing the bill for this joint Anglo–American operation, the U.S. gave Kashani $10,000 to organise massive demonstrations in central Tehran, together with other ayatollahs who also brought their supporters out onto the streets.

Amidst these demonstrations, the Shah appointed General Zahidi as prime minister and appealed to the military to come out in support of him.

Wider protests developed in which anti-Shah activists were beaten up and pro-Shah forces, including elements in the military, seized the radio station, army headquarters and Mossadeq’s home, forcing the latter to surrender to Zahidi.

The C.I.A. also helped to mobilise militants of the Fadayan-e-Islam in these demonstrations; it is not known if Britain also did.

The Fadayan’s founder and leader, Navab Safavi, is believed to have had associations at the time with Ruhollah Khomeini, a Shia cleric and scholar based at the shrine city of Qom in Iran. According to Iranian officials, Khomeini, then a follower of Kashani, was among the MI6/C.I.A.-sponsored crowd protesting against Mossadeq in 1953.

Fadayan-e-Islam’s members would act as the foot soldiers of the Islamic revolution of 1979, helping to implement the wholesale introduction of Islamic law in Iran.

Thanking Kashani

1953 caricature of Kashani with Union Jack. Photo: Unknown author / Wikimedia Commons.

After Mossadeq’s overthrow, the British received a report from the new Iraqi ambassador in Tehran, telling how the Shah and Zahedi had together visited Kashani, “kissed his hands, and thanked him for his help in restoring the monarchy.”

The Shah soon assumed all powers and became the “dictator” preferred by the British ambassador. The following year a new consortium was established, controlling the production and export of Iranian oil, in which the U.S. and Britain each secured a 40 percent interest — a sign of the new order, the U.S. having muscled in on a formerly British preserve.

Kashani, meanwhile, faded from political view after 1953, but he acted as Khomeini’s mentor and the latter was a frequent visitor to Kashani’s home. Kashani’s death in 1961 would mark the start of Khomeini’s long rise to power.

Despite eventual U.S. management of the coup, the British had been the prime movers, and their motives were evident.

As a former Iranian ambassador to the U.N. until the 1979 Islamic revolution, Fereydoun Hoveyda, claimed years later:

“The British wanted to keep up their empire and the best way to do that was to divide and rule.”

He added: “The British were playing all sides. They were dealing with the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and the mullahs in Iran, but at the same time they were dealing with the army and the royal families.”

Hoveyda continued: “They had financial deals with the mullahs. They would find the most important ones and would help them…The British would bring suitcases of cash and give it to these people. For example, people in the bazaar, the wealthy merchants, would each have their own ayatollah that they would finance. And that’s what the British were doing.”

"Made in Britain"

In her memoirs, written in exile in 1980, the Shah’s twin sister, Ashraf Pahlavi, who pressed her brother to assume power in 1953, observed that “many influential clergymen formed alliances with representatives of foreign powers, most often the British, and there was in fact a standing joke in Persia that if you picked up a clergyman’s beard, you would see the words ‘Made in England’ stamped on the other side.”

Although exaggerating with her ‘Made in England’ claim, Ashraf neatly summed up the British view of the Islamists – that they could be used to counter threats to U.K. interests.

During the 1951–1953 coup planning period, Kashani was seen by the British as too much of an anti-Western liability to be a strategic ally. But his forces could be used to prepare the way for the installation of pro-Western figures, and be dropped as soon as their tasks for the imperial powers had been performed.

Kashani’s successor, Ayatollah Khomeini, took over the country following the 1979 revolution, presiding over an Islamic theocracy until his death a decade later.

Main photo: Mohammad Mossadegh © Wikimedia.

Source: Consortium News.