Roughly 50 years after the Yom Kippur War [or October War], several Palestinian militant groups, led by Hamas, launched a coordinated offensive against nearby Israeli cities, Gaza border crossings and adjacent military installations, which led to Israel’s rapid, lethal counter-offensive.

After the brutal Hamas offensive, odd even in view of the violent history of the region, the Israeli launch of a massive ground assault to destroy Hamas poses an existential threat to 2.3 million Gazans in the region.

That’s the standard narrative. But it’s not what has been taking place behind the façade. That’s far worse.

The Hamas-Israel War is not just the first major direct conflict within Israeli territory since the country’s founding. It is also the latest manifestation of Israel’s “strategy of tension” dating from the aftermath of the 1973 Yom Kippur War and the rise of U.S. economic and military ties.

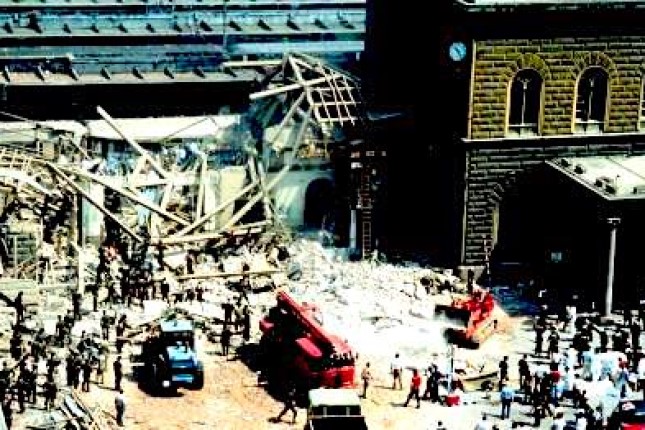

This tension had been seen in several countries, including during Italy’s “years of lead,” a period of extraordinary social turmoil, political violence and economic volatility that lasted two decades.

Aftermath of the bombing at the Bologna railway station in August 1980 which killed 85 people, the deadliest event during the “years of lead” in Italy. Photo: Beppe Briguglio / Patrizia Pulga / Medardo Pedrini / Marco Vaccari / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0.

Starting in the late 1980s, it was marked by a wave of false-flag terror, first attributed to the far-left but later linked with far-right, as well as Italian and U.S. intelligence agencies, as covered in Anna Cento Bull’s 2012 book Italian Neofascism: The Strategy of Tension and the Politics of Nonreconciliation and Rosella Dossi’s Italy’s Invisible Government, Overt Democracy Covert Authority published in 2001.

The strategic objective is to use a general sense of insecurity against targeted groups and to buttress an increasingly repressive government. As geopolitics replaces development, economic welfare suffers, but the perceived common enemy is expected to “unite the nation.” (See Franco Ferraresi’s 1997 book Threats to Democracy: The Radical Right in Italy after the War and Daniele Ganser’s 2005 book NATO’s Secret Armies: Operation Gladio and Terrorism in Western Europe.)

Historically, the strategy of tension has paved the way to neoliberal economics; for example, the 1973 Pinochet regime relying on U.S.-trained Chicago economists in Chile, as Juan Gabriel covers in his his 2008 book Pinochet’s Economists: The Chicago School of Economics in Chile.

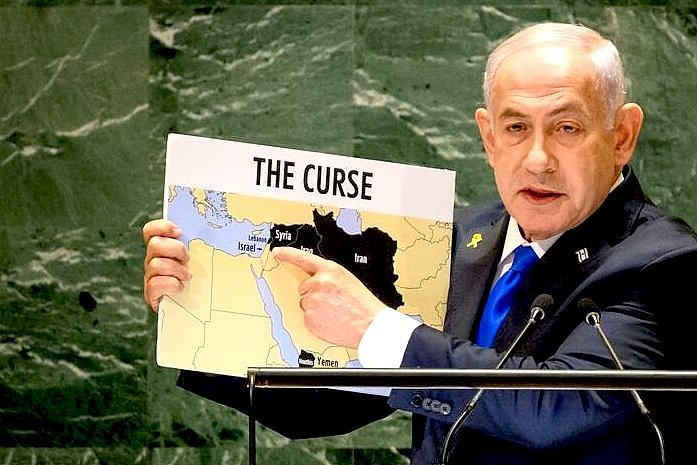

In contrast to the standard narrative, the Hamas war is manna from heaven to Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu’s far-right government, which has escalated the suppression of Palestinians ever since international attention was focused on the proxy war in Ukraine.

It certainly did not come out of the blue. Netanyahu himself has contributed to the creation of Hamas since the 1990s. In effect, the strategic tension has lasted more than five decades in Israel. But since late 2022, it has been accelerated by the most far-right cabinet in Israel’s history.

Legitimisation of Far-Right Extremism

Bezalel Smotritz celebrating election victory in March 2021. Photo: Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0.

In July, the ex-chief of Mossad Tamir Pardo (2011-16) charged Netanyahu with bringing parties “worse than the Ku Klux Klan” into his government. He had a point.

Since the tumultuous 1970s, far-right politics, violent Messianic settlers and ultra-nationalists such as Rabbi Meir Kahane’s Kach Party have given rise to far-right movements, massacres of Palestinians and political parties like Otzma Yehudit (Jewish Power), Kach’s ideological successor. Its leader, Itamar Ben-Gvir, first gained national notoriety in 1995 by brandishing a Cadillac hood ornament that had been stolen from Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s car. “We got to his car, and we’ll get to him too,” Ben-Gvir said proudly. Weeks later, Rabin, the architect of the peace process, was assassinated.

As Netanyahu’s minister of national security, Ben-Gvir has espoused Kahanism. As a settler, he lives in an illegal settlement. He has openly called for expulsions of Arab citizens. In January, his provocative visit to the Temple Mount, the locale of al-Aqsa Mosque, contributed to the onset of the ongoing turmoil.

Another fatal mistake of the Israeli government has been the decision of Netanyahu’s Energy Minister Israel Katz that no “electrical switch will be turned on, no water hydrant will be opened and no fuel truck will enter” until the “abductees” would be free, as he said in this Tweet:

Reminiscent of Nazi practices, such collective punishments are morally flawed and counter-productive in practice. When revenge massacres are imposed on innocent civilians, they will breed new resentment, new bitterness and generations of resistance.

Through his 20 years of participation in Israeli cabinets, Katz has fought for more resources for settlements. Opposing any two-state solution, he pushes for the annexation of the West Bank and wants to make Gaza Egypt’s problem.

Netanyahu’s minister of finance is Bezazel Smotrich, a vehement opponent of a Palestinian state and a self-proclaimed fascist, racist and homophobe, who also lives in an illegally built West Bank settlement.

In 2021, he declared that Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, should have “finished the job” and kicked all Palestinians out of Israel when it was founded. He believes that members of Israel’s Arab minority communities are citizens, but only “for now.”

When Smotrich was entrusted with much of the administration of the occupied West Bank, the fox took over the hen house. It was a signal to Palestinian Arabs: Leave!

These are the hollow men in Netanyahu’s government. Neither they nor their peers will ever support policies recognising the sovereign and human rights of the Palestinians.

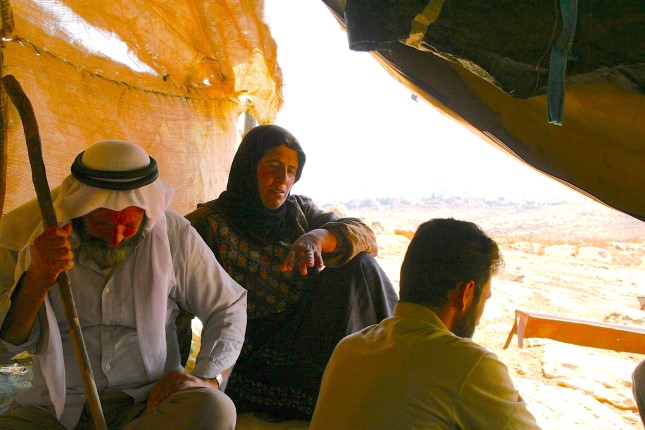

Main photo: Sept. 16, 2006: A family in Susiya in the south hills of al-Khalil, a Palestinian area often attacked by Israeli colonists from the nearby settlement of Hebron © Michael loadenthal / Flickr / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Source: Consortium News.