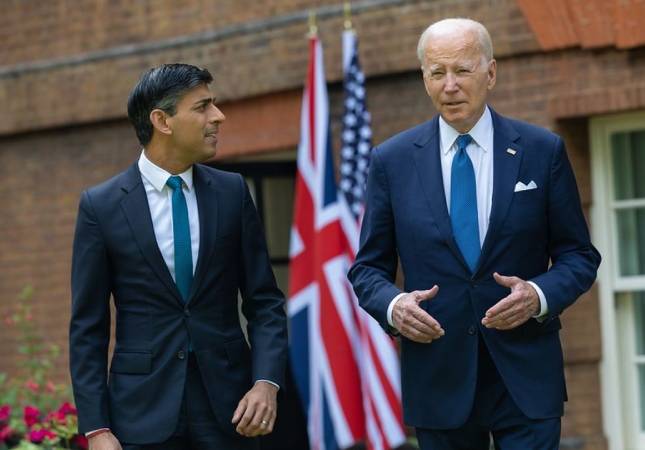

US President Joe Biden met for roughly an hour in the morning with British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak before attending his first bilateral reception with King Charles III, which was the nominal reason for his visit.

Given Biden’s discussion with Sunak was to help prepare the next stage of a war between NATO and Russia, his chat about environmental issues with the British monarch that afternoon assumed the character of light relief.

Biden’s only comment to the media was to describe the US-UK relationship as “rock solid”. He reportedly told Sunak he “couldn’t be meeting with a closer friend and greater ally.”

This is not purely for the cameras. The US and the UK are closely aligned on their key goals in NATO’s war in Ukraine, with Britain prepared to do whatever is asked of it by its dominant imperialist partner.

Supposed differences and points of “awkwardness” talked up in the media before the meeting are largely overblown. None more so than the issue of cluster bombs, on which several sensationalist and performatively hand-wringing articles have been written.

The US announced last week that it would be supplying the weapons to Ukraine. Neither the US, nor Russia, nor Ukraine have signed the Convention on Cluster Munitions. But America’s NATO allies were required to mutter polite, pro-forma disagreements before moving on to next business.

Sunak stated simply, “The UK is a signatory to a convention which prohibits the production or use of cluster munitions and discourages their use,” adding that it was “right that we collectively stand up to” the Russian invasion. The Financial Times reported, “privately British officials said talks on the issue were amicable.”

Writing in the Guardian about Biden’s visit, diplomatic editor Patrick Wintour was close to the mark in writing, “the open disagreement over the US decision on Friday to supply cluster munitions to fill an ammunition gap is less important. Britain, as a signatory to the cluster munitions convention, can hardly approve of the US decision”.

His appraisal was echoed by Lord Ricketts, who previously served as the UK’s first national security adviser, who in the Daily Mirror described Washington’s allies as “all very uncomfortable with this.

“We have all of us, apart from the Americans, signed up to the convention which means we don’t produce or stockpile or use these weapons. They are indiscriminate weapons, of course. I think we do owe it to the Ukrainians to understand why they need these weapons.

“This offensive that they have launched, there is a lot riding on it. If it stagnates, bogs down, the risk is this war will just continue.” He added: “It is a hard choice of the kind that countries have to make in war time. I am uncomfortable with it, yes I wish it wasn’t being done, but I think we can understand why they are doing it.”

According to Wintour, more substantive points of tension are Washington’s apparent blocking of British Defence Secretary Ben Wallace’s bid for the post of NATO Secretary-General—current chief Jens Stoltenberg was encouraged to stay in the post a year longer—and the UK’s support for a clear NATO “membership pathway” being offered to Ukraine.

UK Foreign Secretary James Cleverly recently commented, “I think the UK’s position would be very, very supportive if we moved on from the membership action plan recognising that the offer to Sweden and Finland didn’t require that, and Ukrainians have demonstrated their commitment to reform the military for requirement of NATO membership through their actions on the battlefield.”

The two issues are related, both rooted in judgements over the pacing of the war and Biden’s need to keep the NATO coalition together—particularly its major members Germany, France and the UK. Most accounts agree that Wallace’s candidacy was torpedoed, but that the more European-Union friendly choice Ursula von der Leyen, the current President of the European Commission, was also rejected.

Wintour adds that the UK and US are “increasingly a long way apart on how to handle Ukraine,” before noting that “The US disapproves if the junior partner goes public on any disagreement, or is perceived to be trying to bounce Washington into action. Pushiness, some say, was the undoing of the Nato secretary generalship ambitions of Ben Wallace, the UK defence secretary, after he tried to force the pace on arms supplies.”

The same question is posed on a higher level by this week’s Vilnius NATO summit, with Germany and the US at this point backing a concluding statement avoiding full endorsement even for a “pathway” to NATO membership for Ukraine. They are looking to draw the line at support for a multilateral framework boosting the supply of financial and military support.

This hesitation reflects the tightrope being walked by Washington in pursuing the war with enough force to splinter Russia socially and politically in pursuit of regime change, while maintaining enough formal separation between NATO and Ukraine to forestall a significant escalation by the Kremlin which the imperialist alliance is not yet prepared for.

These are purely tactical divisions over how best to pursue a shared perspective of stepped-up aggression against Russia. As a far smaller military and economic power than the US, Britain for the most part serves as an outrider for NATO aggression, constantly championing the provision of more weapons and greater NATO involvement than Washington presently advocates but which it later adopts as policy—as it has already done with the provision of battle tanks and the supply of F16 fighter jets.

When Washington is ready to move, having secured the resources at home and the political agreement abroad, Britain is turned from a grandstander to a trailblazer—an example to the rest of Europe. Following Biden’s visit, Sunak’s spokesperson reiterated the UK’s position that “Certainly, we do want to support Ukraine on the pathway to joining the alliance, the exact mechanisms for that are for discussion with Nato allies,” but rejected suggestions of a divide between London and Washington, “I have seen that reporting, but I don’t believe that’s accurate.”

With Stoltenberg ruling out an immediate offer of NATO membership, the UK and US will most likely work alongside France and Germany on a multilateral text laying down the framework for member states to work together on the provision of military aid, advanced weapons and finance without this formally proceeding through NATO’s structures.

Moreover, Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba is claiming that NATO has in fact, as Cleverly suggested, already agreed that Kyiv will not have to meet a series of targets within a Membership Action Plan (MAP) to join the alliance, thereby shortening “our path to NATO.”

Sunak also agreed to work with Biden and the US in securing Swedish membership of NATO by overcoming the opposition of Turkey and Hungary.

Photo: The Prime Minister welcomes the US President to Downing Street ©Simon Walker.

Source: World Socialist Web Site.