This happened in late July in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Moshe Benedek, a wealthy Israeli businessman, was kidnapped at gunpoint from his own car, stranded in a traffic jam. His kidnappers held the businessman for ransom, offering his relatives to buy him out for about USD 1,200. The family, however, opted out of paying the ransom since no guarantees of his release had been offered and instead chose to whip up an international-scale scandal culminating in a special police operation that resulted in the businessman's release at no cost.

Incidents of this kind, with people getting kidnapped in broad daylight by being dragged out of their cars stuck in heavy traffic, are commonplace in Brazil's major cities. This explains why armoured vehicles are in such high demand in the country. As the locals explain, such cars offer a chance to survive a gunshot or a stray bullet from automatic fire if you are unfortunate to get caught in a firefight. That said, Rio's bigger gangs are known to have used grenade launchers and large-calibre machine guns, making a trip to some of the city's neighbourhoods a true adventure.

Photo: YouTube.

In Brazil, it is not uncommon for an individual to get mugged in a city street and even get killed afterwards. The country is ranked as having one of the highest per capita rates of violent deaths. From 2001 to 2015, someone was murdered there every ten minutes. Over that decade-and-a-half-long stretch, Brazil witnessed dozens of bank robberies and gang-style raids taking place in the country's cities all over the place. The nation's all-time record was set in 2017, with nearly 64,000 reported deaths at the hands of criminals. That's three to four times worse than in the US, where gun fights are frighteningly common, too.

The laughably modest ransom of USD 1,200 demanded from the relatives of the kidnapped Israeli businessman was hardly exceptional. In Brazil, it is not unusual for people to commit felonies literally for a pittance. A car may pull up at a curb as if to ask a passer-by for directions, only for the driver to pull out a gun and rob the passer-by of his cellphone or headset.

The roots of violent crime

About half of the 210 million Brazilians make less than USD 200 a month. The wealthiest 10% of the country's population earn 100 times that. Brazil's six most affluent families have the same wealth as 100 million of its poorest people.

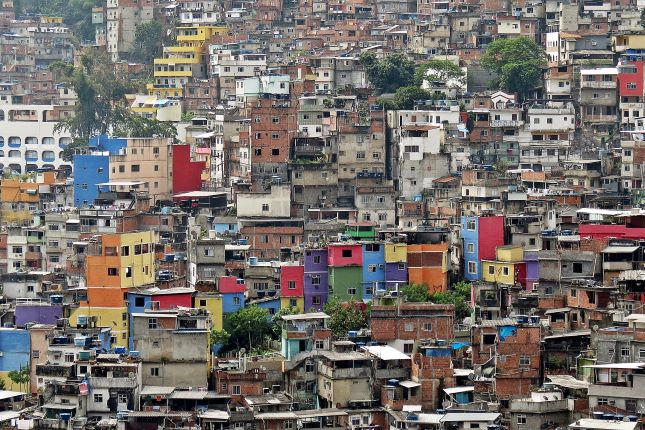

Brazil is one of the most unequal countries in the world. Poverty, failure to find adequately paying employment, and lack of access to education provide fertile ground for crime. The inhabitants of favelas, who, for the most part, are descendants of formerly enslaved people who were freed in the late 19th century but were not provided with land or property, often fail to find a job and are forced to resort to robbing or killing.

Rio de Janeiro's favelas. Almost half of Brazil's population lives in slums such as these. Photo: Pinimg.

Adding oil to the fire, the problem is made even worse by the predominance of prison sentences dished out by criminal courts to punish many of the pettiest crimes and misdemeanours. Large drug cartels that have divided the country into spheres of influence actively use overcrowded prisons to recruit lone-wolf criminals or members of smaller street gangs into their ranks.

Brazil has struggled to solve the country’s crime problem for decades, if not centuries. Law enforcement officers, jurists, sociologists, politicians, clergypersons and military members have spent endless hours arguing about how to deal with the issue. The country has become a mecca for crime scholars from all over the world who come here in droves to study crime.

The fight against crime has now become a major point of contention between Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil's current president, and the nation's former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. They are battling each other for the highest office in the country. Brazil's next general election will be held in October 2022.

Building on past experience

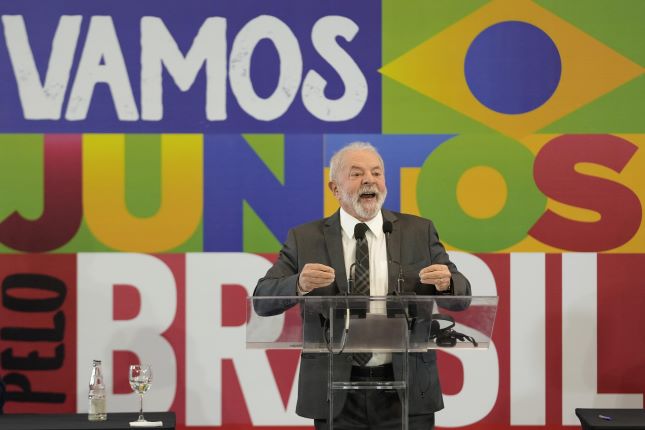

When asked by journalists about his campaign programme, socialist candidate Lula da Silva famously replied: "Don't ask me what I am going to do. Look at what I have done already." Coming from a head of state who ruled Brazil during the country's strongest economic growth and prosperity, these remarks seem appropriate only at first glance. It is worth recalling that during the presidencies of Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff, his successor, that crime in Brazil exploded to reach disastrous levels, peaking at its highest level in 2017.

Presidential candidate Lula da Silva at a campaign rally in São Paulo. Photo: Venezuelanalysis.

The Socialist government at the time banked on social programmes that included welfare benefits for the families of inmates payable to them for as long as they were incarcerated. In parallel, the authorities were taking firearms off the streets via gun buy-back programmes, trying to reassure the Brazilians that the state would take care of their safety. Coming from a low-income family, Lula da Silva could hardly have acted any differently as he understood well why his neighbours and friends were turning into mobsters and why there were muggings and murders on city streets. This is the understanding that he brought with him into politics.

Jair Bolsonaro, a former officer and member of a special forces unit, who transitioned to politics from the military, advocated a different and predictable approach for someone with his background. Tropical Trump (as his detractors nickname him for the similarity of his views to those of the famous US former president) keeps saying that one has to be self-reliant, first and foremost. When it comes to fighting crime, Bolsonaro believes that the root of the problem is not in that the state is not helping enough but in that it is not strict enough in punishing crime.

Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais (Special Police Operations Battalion) is an elite specialised unit of the Military Police of Brazil's State of Rio de Janeiro created for the primary purpose of conducting special operations in favelas. Photo: Snobium.

Under Bolsonaro, the number of robberies and homicides in Brazil began to fall, reaching its lowest level in 2021. With 41,000 violent deaths and hundreds of thousands of robberies a year, Brazil is still far from being safe, as Israeli businessman Moshe Benedek sadly learned from his personal experience. There is no denying that the country has made much progress in its fight against violence.

The government's success is mainly due to a series of strict measures. First of all, Bolsonaro pushed through several bills that not only increased penalties for robbery and murder but also made it easier to prosecute police officers and local officials for corruption and grand larceny. In addition, the government allocated federal funds to build new prisons.

Interestingly enough, these bills were drafted by Justice Minister Sergio Moro. As a judge, Moro put Lula da Silva and dozens of other top officials behind bars on corruption charges. Sentenced to nine and a half years, the former president got out of prison much earlier.

Gun rights

During his campaign rallies, Jair Bolsonaro often makes a hand gesture to mimic a raised handgun. The relaxation of gun laws is perhaps one of his most popular decisions. Since 2019, the president has initiated more than 30 amendments enabling ordinary citizens to buy and use guns for self-defence. Since then, Brazil has been arming itself without restraint. During Bolsonaro's presidency, the number of firearms owned by Brazilians doubled to two million. More than 700,000 citizens have obtained firearms licenses – a sixfold increase from 2018.

Jair Bolsonaro served in the Brazilian army's field artillery and paratrooper units for 17 years. Photo: Morning Star.

It is worth noting that the number of legally registered firearms in Brazil (2 million) is merely a fraction of the actual tally estimated at 30 million guns. This disparity is one of the main arguments favouring relaxing gun control regulations. "If gangsters are armed anyway, is it fair for us to remain defenceless?", Bolsonaro's allies ask. The president keeps emphasising that anti-gun legislation passed by the socialists helps criminals go unpunished and should therefore be repealed.

Since Bolsonaro came to power, new shooting ranges have been springing up in Brazil almost daily. Shooting tournaments are also common across the country. For instance, Brazilians of German descent in the southern states hold an annual Schützenfest, a traditional fair where guests drink beer and fire various weapons.

A visitor holds a weapon during the Shot Fair Brasil, an arms exhibition in Joinville, Santa Catarina state. August 5, 2022. Photo: Albari Sosa/AFP via Getty Images.

The correlation between lax gun laws and crime rates still divides experts. Many sociologists and law enforcement officials argue that a large number of firearms people own leads to more gun violence. For example, high-ranking police officials tried to discourage President Bolsonaro from relaxing gun control measures, confident that criminals would upgrade their firearms and continue to attack passers-by.

But Bolsonaro has taken a logical and cynical approach to fight crime. In his view, a revolver tucked inside a man's belt or a smaller handgun kept in a woman's purse may not save Brazilians from robbery. On the other hand, there is no knowing if and when a robbery attempt may occur. What matters is that gun ownership gives greater peace of mind which translates into more votes when Brazilians go to the polls.

The state will take care of its people

Regarding gun control, Lula da Silva is the opposite of Bolsonaro. In 2003, during his first term in office, Lula da Silva pushed for stricter gun safety legislation, banning ordinary Brazilians from buying guns. For a short time, the move led to a decline in crime rates, but violence started growing again in 2007. Millions of Bolsonaro supporters are now concerned that their gun rights will be limited again in the event of Lula da Silva's return to power. Therefore, it is unsurprising that many Brazilians want to obtain firearms before the next presidential election.

Lula da Silva's track record in the war on crime, the primary issue during this election cycle, is relatively poor. However, he can still win the presidential race thanks to the support of the poorest sectors of society. As mentioned, the poor make up about half of the country, although some are not old enough to vote. Incidentally, there are political analysts in Brazil who refer to Lula da Silva's programme as "political necrophilia". In their opinion, he had promised voters a repeat of the years of prosperity, an era in the early 2000s when public welfare multiplied, and the government spent a lot of money on social programmes for the poor.

Lula da Silva. Photo: AP.

If truth be told, Brazil's wealth did not have much to do with Lula da Silva's policies. It was mainly created by China; whose growing economy consumed Brazilian exports in huge quantities. When China shifted its focus to stimulating domestic demand in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Brazil began sliding into poverty. No wonder crime rates started soaring at the same time.

The vicious circle

Lula da Silva and Jair Bolsonaro have made valid arguments supporting their approach to fighting crime. The main issue with their programmes is that they are too radical. Left-leaning in his outlook, Lula da Silva emphasises that the state will take care of everything. Bolsonaro, on the contrary, takes a stance typical of his political orientation: if there is less state involvement, people will be able to take care of themselves.

Lula da Silva calls for considering the rights of all Brazilians and distributing social benefits among them. This is a fine method of combatting crime, assuming there is something to spread. However, the Brazilian economy is not at its best right now. Bolsonaro is slashing welfare programmes, forcing people to earn money any way they can. This increases poverty and leads to more violence which, in turn, must be curbed by using firepower. Neither a kind word nor a gun will suffice to solve Brazil's age-old crime problem. In all likelihood, Brazil needs to find the middle way.