Possible defeat of Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his electoral bloc in the general elections in Turkey could blow up the entire region of the Middle East. Simultaneously, presidential and parliamentary elections will be held on May 14, and as the appointed date approaches, the election race is turning into a war of opinion polls.

Thus, according to the Areda Survey, 49.8% of the survey participants support the incumbent Turkish President Erdogan, and his main rival, Kemal Kılıçdaroglu, is supported by only 21.7%. Whereas, according to a survey by Aksoy Research, Kılıçdaroglu with 55.6% is significantly ahead of Erdoğan with 44.4%.

In Turkey, such dispersion in the results of published polls does not bode well. It usually leads to the fact that after the election results are announced, the losing side officially disputes them − up to mass protests and colour revolution. This scenario is all the more likely because Erdoğan categorically displeases the US and the EU, whose media outlets are spreading information about the declining popularity of the incumbent authorities.

Another sign that Erdoğan is preparing for a serious test is that meetings between the American ambassador Geoffrey Flake and leading members of the opposition People's Republican Party (PRP) have long been systematic. The latter took place at the end of March in Ankara at the headquarters of the CHP, and at the meeting CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu was accompanied by his chief adviser Unal Ceviköz, who recently stated that if the opposition wins in relations with Russia, Turkey will emphasize its membership in NATO. The opposition also plans to withdraw Turkish objections to Sweden's and Finland's membership in NATO.

The situation is ripe for a change of power in the country. The economic situation in Turkey is critical. At the end of 2022, inflation was 64.3% and the rise in food prices was 77.9%. The Turkish lira has fallen by 30% against the dollar over the year.

On February 6, 2023, Turkey was shaken by a powerful earthquake. Its victims were more than 50 thousand people. The large number of deaths was caused by the poor quality of construction in the earthquake-prone region. And this severely undermined the position of Erdogan and his party, which had just begun to regain popularity thanks to higher salaries for state employees and other economic stimulus measures.

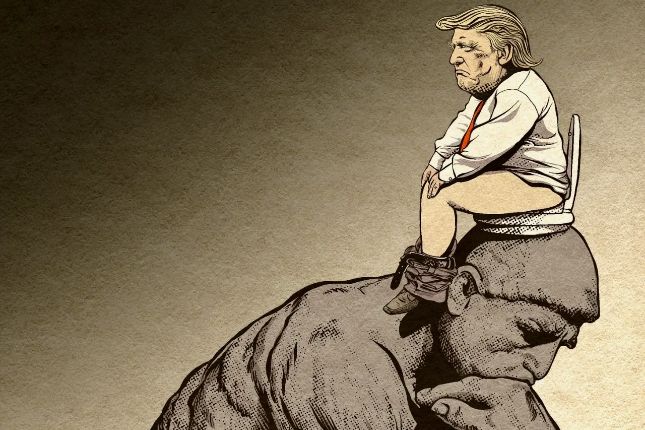

Erdoğan had the opportunity to postpone the elections by six months, using the aftermath of the earthquake as an excuse. He decided that a delay might play against him, but it is already evident that this was probably an overconfident decision by a leader who has been in power for twenty years.

In foreign policy, Turkey's position is also unenviable. From the former successes of neo-Ottoman policies based on moderate Islamism, from Libya to Central Asia, only strong relations with Azerbaijan remain as an asset. Erdoğan himself has managed perfectly well to keep Turkey stable, maneuvering between the centers of power − the Arab world, the United States, the EU, Iran and Russia − as much as possible. But if the power in the country were to change, that balance would be upset. The consequences could be most devastating. Today, all regional stability essentially depends on the state in which Turkey will emerge from the general elections in May.

There is no way to separate anymore

On March 10, Iran and Saudi Arabia (KSA) agreed to restore diplomatic relations after Beijing-brokered talks.

On March 23, it became known that Saudi Arabia and Syria were also planning to restore diplomatic relations.

These two events draw a line under Erdoğan's Middle East strategy. Normalization of relations between Saudia Arabia and Syria means the end of Turkey's attempts to expand its zone of influence in Syria. So the Arab Spring, which the Turks tried to use to expand their influence in the Arab world, has come to naught and never resulted in the formation of any sustainable zone of influence.

On the other hand, the normalization of relations between Iran and Saudia Arabia under the patronage of Beijing means that Turkey's claim to play the role of a counterweight to Iran's influence in the region in the interests of the Arab world, primarily the oil monarchies of the Persian Gulf, has also collapsed.

Turkey's incursion into northern Iraq has become a trap for the Turkish army. Based at the Zlikan military base in Ninewa province in northern Iraq, military units are increasingly targeted by pro-Iranian Shiite groups.

On March 25, an international arbitration court ruled that Turkey had violated a bilateral agreement with Iraq by facilitating independent pipeline flows by the Kurdistan Regional Government. After that, oil exports from northern Iraq via the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline were suspended. Oil companies were transporting about 400,000 barrels of oil per day through Turkey.

Grey oil exports from Syria and Iraq were one of the economic pillars of Erdogan's power. But now it has been called into question as well.

Where will the change in power lead to?

The main threat for Turkey if the opposition comes to power is that Ankara will lose its room for manoeuvre and become a puppet in the hands of the United States. In this case, Turkey could quickly turn from an inconvenient but independent and agreeable partner into a hotbed of regional tensions.

In addition to the Middle East, there is also the conflict over Ukraine.

According to The Wall Street Journal columnist Jared Malsin, it was Erdogan who benefited most from the conflict over Ukraine. He was able to strike a delicate balance that allowed him to combine arms deliveries to Kyiv with direct, trusting contacts with Putin. In an environment of acute geopolitical confrontation, Erdogan was able to reap the benefits of the grain deal and promote the idea of Turkey as a gas transport hub.

The catch is that it is Erdogan who has won, not Turkey. Any other leader in Ankara who fails to continue this virtuoso brinkmanship will quickly lose all these Erdogan wins. Even a slight shift in the balance to the West would cause Turkey to lose its special role and become a US springboard for pressure on the new "eastern bloc."

Given the fact that Turkey has already lost its reserve of economic and foreign policy stability, this could lead to a full-scale crisis of Turkish statehood. In the early 2000s, Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party laid down a new vector for the country's development by revising Kemal Ataturk's legacy. Therefore, dismantling Erdoğan's legacy is doubly dangerous.