Reports show that Japan and the US will draft their first joint document on expanded deterrence policy, which will include a clause affirming nuclear weapons will be included in US methods to defend Japan. However, it might be premature if Japan feels moved by this.

Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun, citing sources, reported that the document will specify measures that the US could take in peacetime and emergencies; as well as conditions under which the US could take retaliatory actions against third countries, and what those measures could be, under the backdrop of so-called threats from China and Russia. The foreign and defense ministers of Japan and the US will discuss the details at a meeting in Tokyo later this month, according to the report.

Although discussions on the matter started in 2010, when Washington and Tokyo established the Extended Deterrence Dialogue to explore ways to sustain and strengthen extended deterrence, the timing of the news this time is quite intriguing.

If seems that Japan wishes to secure a written commitment over nuclear protection before the US election, to prevent Washington from reneging on its promises after the Oval Office sees a change in its occupant, Da Zhigang, director of the Institute of Northeast Asian Studies at Heilongjiang Provincial Academy of Social Sciences, told the Global Times.

Both the US and Japan have their own calculations behind the push for this joint document. Japan wants to boost its deterrent capabilities through military alliance with the US. Washington hopes to make Tokyo a thornier pawn in its "Indo-Pacific Strategy." Claims of "threats" from China and Russia are merely far-fetched excuse - the US simply wishes Japan to be more proactive toward China and Russia under the nuclear umbrella, so as to alleviate US pressure in countering both countries.

The essence of today's US nuclear umbrella in the Asia-Pacific region is not about protection. Rather, it serves as a platform for the US to disrupt regional stability among major powers through providing excuses to enhance strategic offensive capabilities of US allies.

Japan, a non-nuclear weapon state, would hardly become a primary target for nuclear strikes, if there will be one. Still, the US is now pulling Japan in its "nuclear protection circle" while mulling to deploy nuclear weapons to Japan. In that scenario, Japan could be viewed as a nuclear-weapon state. The US is pushing Japan to be the next battleground. And by promoting the joint document, Japan demonstrates its readiness to be considered a potential nuclear target due to its alliance with the US.

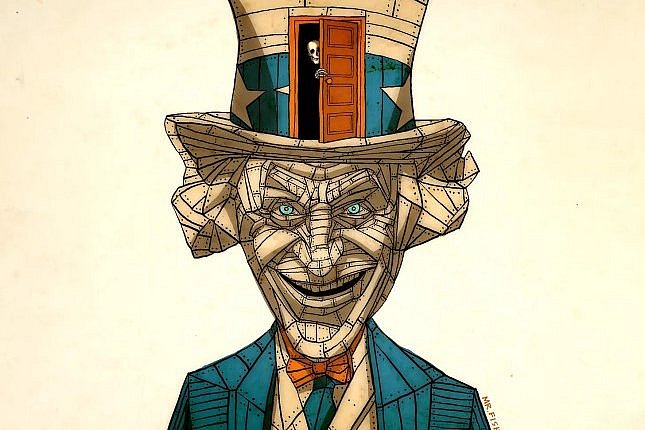

This is hardly protection. Tokyo seems to have a fundamental misunderstanding about what truly threatens Japan: Someone who claims to be an ally and a protector.

The US has been adeptly disrupting regional security dynamics, amplifying regional security threats and heightening concerns among its allies. It then offers so-called security protection to these allies through military measures like the nuclear umbrella, fostering increased dependence on American security. Leveraging this dependence, the US can assert control over these countries, utilizing them to further American global and regional hegemonic ambitions, Da told the Global Times.

How will the US deploy nuclear power to protect Japan? Reports indicate that the details may not be disclosed to the public. However, when Japan truly requests nuclear protection from the US, it suggests Japan faces significant nuclear threats. At such a critical juncture, will the US deploy its nuclear arsenal without hesitation?

In American logic, US' homeland security takes precedence. Its hegemonic interests follow, and the interests of American citizens abroad come next. The interests of US allies rank fourth. That says, if defending Japan with nuclear weapons poses any risk to US homeland security, Washington will think twice, an anonymous military expert told the Global Times. The US' nuclear umbrella only protects itself.

Now, Japan must decide what it wants - peaceful development or being pushed to frontline conflicts.

Source: The Global Times.