Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is vowing to launch an invasion of Rafah, a city located along the Gaza-Egypt border where more than 1.5 million Palestinians currently shelter.

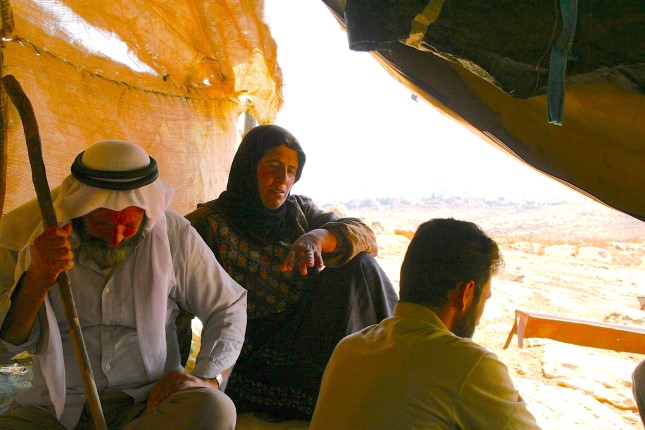

Egypt’s stakes are extremely high given how much spillover from Gaza into the Sinai Peninsula could be destabilizing. Cairo understandably wants this war to be over immediately.

A massive refugee influx into the Sinai from Gaza could result in Palestinians waging an armed resistance against Israel from Egyptian soil — a nightmarish scenario from Cairo’s perspective. Egypt also does not want to be seen as accepting Palestinian refugees in exchange for money from the U.S., which would contribute to perceptions on the “Arab Street” that President Abdel Fatah el-Sisi’s government is complicit in a “Nakba 2.0.”

Understanding Egypt’s vulnerability to spillover from Gaza requires considering Cairo’s other foreign policy challenges too. The Gaza war’s spread into the Red Sea has harmed Egypt’s economy in the form of lost Suez Canal revenue with ships rerouting to avoid the body of water altogether. Additionally, Rafah isn’t the only border security crisis concerning Egyptian officials.

“They’ve got Sudan in the south, which is a mess. To the west, Libya is a mess. So basically, everywhere Egypt looks now is a problem. There’s also the issue of the Renaissance Dam,” noted Kenneth Katzman, a Senior Fellow at the Soufan Center, in an interview with RS.

The U.S. Role

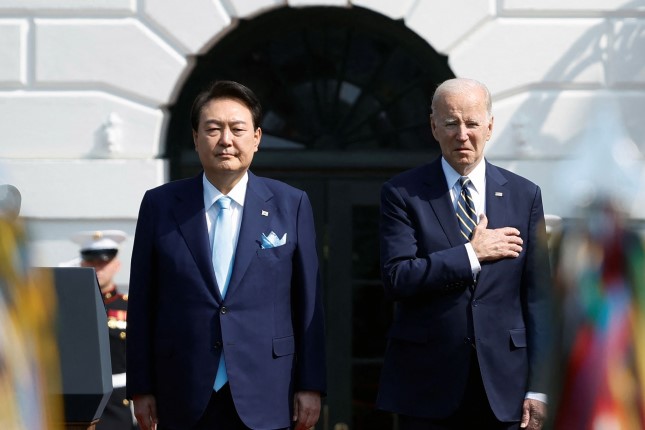

Since October, Egyptian diplomacy has been key to efforts aimed at implementing a ceasefire, negotiating hostage-prisoner swaps, and delivering Gaza humanitarian assistance. As a result, the Biden administration perceives Egypt to be more indispensable than ever. Notably, Biden and his team haven’t recently criticized the Sisi government’s human rights record — a major contrast to Biden’s rhetoric as a presidential candidate.

The White House understands Cairo’s concerns and Biden’s public position is that Israel should not wage a full-scale assault on Rafah without ensuring the safety of Palestinians sheltering there. But Egypt continues to be frustrated with Biden’s refusal to deploy Washington's leverage to pressure Israel into actually changing its conduct on the ground.

“Washington’s support [for Egypt on this front has been] confined to making clear its opposition to any full-scale transfer of refugees, forced, unforced, permanent, or temporary,” Charles Dunne, a former U.S. diplomat who served in Cairo and Jerusalem, told RS.

“It is pushing back on talk in Israel — so far unofficial — that a mass population transfer could be part of the solution to Israel’s Gaza problem,” he added.

“My personal conclusion is that [U.S. officials] probably made the point [to their Egyptian counterparts] that some of the Gazans would inevitably be needed to be let into Egypt in order to prevent a greater humanitarian catastrophe as the Israelis move military operations closer to Rafah,” Dave DesRoches, an assistant professor at the National Defense University in Washington, DC, told RS. “My guess is the Egyptians are concerned both that the Gazan presence would become permanent as well as that Egypt would be seen as abetting the Israeli military operations,” he added.

If Israel wages an all-out assault on Rafah and there is a massive displacement of Palestinians into Egypt, Washington would probably financially assist Cairo. But Katzman belives the White House is likely more focused on trying to prevent that from happening. “My impression is that [the Biden] administration is not really tackling the idea of what if there is a flood of refugees into the Sinai, while I think [its] strategy is to make sure that doesn’t happen in the first place,” he told RS.

Katzman added, “The U.S. is encouraging Israel to coordinate with Egypt to the extent possible, which I think is happening. But beyond that, I don’t think the administration has done any planning because they don’t expect that worst case scenario to happen.”

“Cairo worries that even entertaining the idea for emergency planning purposes could be seen as a green light to the IDF. That appears to be where we are for now, and Cairo has focused on building a fortified buffer zone along the border with Gaza to prevent a refugee crisis,” said Dunne.

Red Sea Crisis

Another important aspect of U.S.-Egypt relations amid the Gaza war and its regionalization is the Red Sea security crisis. Since November, the Houthis have been launching missiles and drones at ships off Yemen’s coast, claiming to support Gaza by targeting vessels linked to Israel, the U.S., and the UK. As of last month, Egypt’s Suez Canal revenue had decreased by 40 to 50 percent throughout the crisis, according to Sisi.

Gordon Gray, the former U.S. ambassador to Tunisia, told RS that there is “strong incentive for Egypt to assist the U.S. efforts to guarantee freedom of the seas” given what is at stake for Egypt in terms of Suez Canal fees amid Houthi maritime attacks.

But despite economic setbacks from the Red Sea security crisis, Egypt did not join Operation Prosperity Guardian (OPG) and Cairo has played no official role in the Washington-led bombing campaign against the Houthis that began almost two months ago. This is not because Cairo doesn’t share the West’s concerns about the Houthi attacks on vessels. To the contrary, Egypt and the U.S. strongly agree that no Yemeni group should be allowed to disrupt maritime shipping in the region.

In fact, when Saudi Arabia launched Operation Decisive Storm in March 2015, Egypt committed its naval forces to provide security in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. At that time, Sisi referred to the Red Sea as an “Arab lake” and identified the Bab al-Mandab as important to “Egyptian and Arab national security.”

Public opinion at home mostly explains Cairo not joining OPG nor formally supporting the U.S.-UK strikes. Many Egyptians would now see their government overtly aligning with Washington and London against the Houthis as Cairo facilitating Israel’s war on Gaza.

“Egypt has refused to join [OPG] and, while it’s possible that Egypt is making some behind-the-scenes contribution, any such contribution is pretty much invisible to the naked eye at the moment. If anything, it’s the very least they can get away with doing,” according to Dunne.

DesRoches believes that the Egyptians have probably been allowing London to use Egyptian airspace for bombing Houthi targets in Yemen.

“Extrapolating, I’m confident that U.S. support, intelligence, and resupply flights are probably transiting Egyptian airspace,” he told RS. “I have a slightly lower degree of confidence that the Egyptians share intelligence and the common operating picture from their various assets to locate missile tracks and launch sites. This is probably limited more by the lack of Egyptian capacity than by any policy decision to not cooperate.”

Ultimately, the U.S.-Egypt alliance remains strong. But Cairo must approach this relationship with more caution given Washington’s role in Gaza’s destruction and its growing isolation in the Arab-Islamic world.

Source: Responsible Statecraft.