In a much-publicized speech at the George Washington University on May 26, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken presented two starkly incompatible visions for the world's future. One is focused on China's "increasingly aggressive, authoritarian one-party state." At the same time, the other is embodied in the U.S.-led coalition of "allies and partners" committed to democracy, human rights and the "international rules-based order."

According to Blinken, "China is the only country intending to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military and technological power to do it." He warned, "Beijing's vision would move us away from the universal values that have sustained so much of the world's progress over the past 75 years."

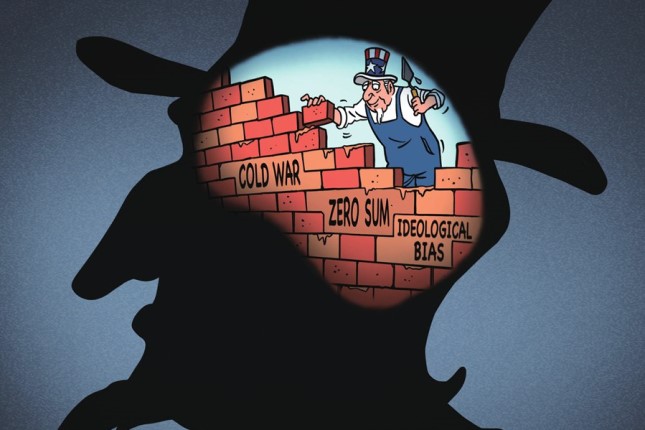

Blinken's rhetoric implies that, regardless of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, the Biden administration sees America's rivalry with China as the most significant challenge facing the United States this century. But instead of the dichotomy between China's "authoritarian one-party state" and America's commitment to "democracy, human rights and the international rules-based order," what we are witnessing today is the competition between China's meritocratic elite – steeped in the Confucian values – and America's postmodern quasi-elite. The latter is morbidly obsessed with countless isms (climatism, transgenderism, multiculturalism, etc.), and steeped in civilizational self-hate. This wokedom completely dominates the media, the academe, big business, entertainment, and government agencies. It is imbued with an ideological zeal comparable to that of the Bolsheviks who were tearing down the Russian state, society and economy a century ago.

Blinken's claim that China is "the most serious long-term challenge to the international order" and that this "will test American diplomacy like nothing we've seen before" treats the maintenance of American global hegemony as an axiomatic necessity. That much was evident from his use of the "international order" interchangeably with the "rules-based order," which in reality means the kind of order dictated by the United States arbitrarily and on an ad-hoc basis.

The U.S. Secretary of State said that Beijing has "the intent to reshape the international order." The Chinese do not conceal their intention to do so. Its leaders have repeatedly stated that they support the "reform of global governance", which would reflect the changing balance of power. Effectively the Chinese want an "international order" based on the classic model of relations between nations pursued by Prince Clemens von Metternich at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and by Dr Henry Kissinger in our own time. That order is vastly different from the U.S.-imposed "rules-based order," which is a hegemonistic construct inside the Washington Beltway.

China's political leadership seeks to reform the world by the essentially conservative concepts of the balance of power and the respect for national and state interests of all actors in the international system. This vision is not guided in any meaningful manner by the ideas of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, or even Mao. Had the Kuomintang won the Chinese civil war in 1949, it is probable that Chiang Kaishek's current successors would have pursued policies that are not qualitatively different from those followed by Ji Xinping and the Standing Committee of the Politbureau of the Chinese Communist Party.

Those policies are based on the unstated but profoundly rooted conviction in the superiority of China's unique civilization and the well-founded but generally unstated belief that Western civilization is ideologically, morally and demographically decadent.

In January 2017, the General Bureau of the Communist Party and the State Council published "Opinions on the implementation and development of the heritage of the great traditional Chinese culture", which called for the "strengthening of cultural self-assurance," greater emphasis on "our values and their revival," and "active political support for the revival of our traditional cultural heritage." This is light years away from the values of the current U.S. government. To wit, President Biden proudly announced almost a year ago that nearly 14% of his 1,500 federal agency appointees identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer. What a success!

It is noteworthy that Blinken said on May 26 that "Beijing wants to put itself at the centre of global innovation and manufacturing, increase other countries' technological dependence, and then use that dependence to impose its foreign policy preferences." This ambition was framed as if it was a form of illegal transgression, even though seeking "to impose its foreign policy preferences" on other countries is exactly what the United States has been doing for some decades now.

"We will bury you," Nikita S. Khrushchev memorably told America 66 years ago. He was wrong: by imposing central planning and collectivized agriculture for reasons of ideology rather than optimal efficiency, the USSR had grossly misused its human and natural resources. The ruling elite in today's China, by contrast, has grounds to believe it has the means to overtake America by winning the long contest in most fields of human endeavour.

Unlike the Western tradition, which emerged in the late Renaissance and then blossomed on both sides of the English Channel in the Enlightenment, China does not treat the individual endowed with natural rights as the key building block of a harmonious polity. It gives absolute priority to the family, the community, the Han nation, and the state. It does not see diversity as a "strength" but as a weakness. Accordingly, China does not accept immigrants and asylum seekers. Most of China's 1.4 billion people accept the system's legitimacy, which ensures stability and prosperity, the tangible proof of "the mandate from heaven."

Scared by Mao's revolutionary misrule, which has a vivid collective memory, the Chinese elite is unwilling to disturb what it sees as the natural order of things. It shares an essentially conservative consensus on gender roles, marriage, family, local community, and the nation. It will continue to uphold the hierarchical order in a competitive society based on merit: good grades, loyalty to the state, and hard work will be rewarded.

The competition between two cultural and political models embodied in the United States and China is accompanied by the rising tension in the Indo-Pacific region. The countries along its shores account for over two-thirds of the world’s population. They produce the largest share of global GDP, possess the most powerful military forces, and depend on the world’s busiest shipping lanes. It is also a potential strategic minefield, extending from the Korean Peninsula in the northeast, across the Straits of Taiwan and the disputed "Asian Mediterranean" of the South China Sea, to Southeast Asia and the Indian Subcontinent.

The rise of China, the corresponding shift in the balance of global power, the desire of some of China's neighbours to contain what they perceive as her assertiveness, and the American quest for allies in the chain of containment are producing a new and dangerous geostrategic mix. In the aftermath of the war in Ukraine – however it turns out – Beijing is almost certain to develop even closer relations with Russia, possibly intending to upgrade their partnership to a formal alliance.

Judging by the adversarial tone of Blinken's speech, the United States acts – paradoxically – as if it wanted to encourage the forming of such an alliance. Blinken declared, "even as President Putin's war continues, we will remain focused on the most serious long-term challenge to the international order – and that's posed by the People's Republic of China." This leaves open the issue of a balanced U.S. strategy to deal with China as a rising power.

The People's Republic is not necessarily an adversary of the United States unless America continues to pursue the strategy of full-spectrum dominance and treat every square inch of the globe as its rightful turf. China wants to be accepted as a great power among great powers in a multipolar world. This does not mean it is making a bid for Eurasian, let alone global hegemony. In any event, to deal rationally with what it sees as "the most serious long-term challenge to the international order," America needs Russia as a partner, not an enemy. For Washington to grasp this simple fact is arguably the most significant security challenge.

Srdja Trifkovic - Serbian-born American author, academic and historian, foreign affairs editor at Chronicles Magazine.