Well, it took long enough for the White House and the policy cliques to notice even the existence of the BRICS, the group of non–Western nations named for its first members.

For many years after Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa coalesced to form this loose but formidable association, in the last years of the last century, it was as if Washington were trying to will the group and all it represented out of existence.

And now look. The first thing the United States does as it acknowledges the BRICS, whose members currently number 11 and counting, is to announce that it will punish those nations belonging to it for … for belonging to it.

Earlier this month President Donald Trump — always the one to get this kind of nitwittery done — announced that he would impose blanket tariffs of 10 percent on all BRICS members — a threat he reiterated two weeks later, with the promise of more to come should the group’s members determine to exercise their sovereignty in the cause of common interests.

The Trumpster on this question said July 6:

“When I heard about this group from BRICS, six countries [sic], basically, I hit them very, very hard. And if they ever really form in a meaningful way, it will end very quickly. We can never let anyone play games with us.”

How’s that for the statecraft of a self-confident nation?

This display of juvenile impetulance coincided with the opening of the BRICS group’s 17th summit, hosted July 6–7 in Rio de Janeiro, as Brazil now holds the group’s rotating presidency.

The agenda included the usual sorts of things for these occasions: trade and investment, inclusive global governance, a global security architecture. This year’s summit also condemned the Israeli–American bombing runs against Iran three weeks prior to the session as “a violation of international law.”

Maybe Trump for once read the briefing papers the C.I.A. delivers to the Oval Office each morning and saw this coming, as he moved instantly to hit very, very hard a second time. Here he is on Truth Social, his digital bullhorn, even before BRICS leaders had checked out of their hotels:

“Any country aligning themselves with the Anti-American policies of BRICS, will be charged an ADDITIONAL 10% tariff. There will be no exceptions to this policy.”

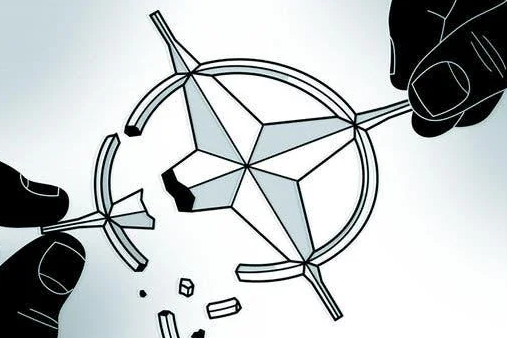

So clumsy, so off the mark, so utterly unaware of where the hands are on history’s clock. It is funny how often what the late-phase imperium intends as displays of strength turn out to be displays of uncertainty, weakness and impotence.

Here I must correct, and not for the first time, a misunderstanding among U.S. officials so common I conclude it is willful. There is not a damn thing the BRICS as a group has ever said, done, or stood for that is anti–American.

This group is about the construction of a world order built on a foundation of parity, the common good and international law. It would welcome the participation of all nations in this world-historical project, not least, given their capital and technology, the U.S. and the other Western powers.

It is anti–American only insofar as it opposes hegemonic power and— putting the point another way — insofar as the United States stands foursquare against all three of the above-noted principles.

I am surprised to note the extent of Washington’s insecurity as the BRICS nations move forward, especially given the lukewarm review the Rio summit got afterward from commentators straight across the board.

Lydia Polgreen, a New York Times columnist, termed the statements coming out of the Rio summit “milquetoast.” The group condemned the Iran bombings but did not name names, Polgreen argued.

On the other side of things, Chas Freeman, the distinguished ambassador emeritus, gave an interesting interview with Glenn Diesen 10 days ago under the headline, “The Old World Is Dying and the New World Struggles to be Born.”

Freeman lauded the BRICS for its accomplishments, among these its work creating alternative financial systems, the New Development Bank, launched in 2012, its outstanding achievement. But, in my interpretation of his remarks, Freeman was critical of the group for not acting more in concert — for not making itself a greater presence in geopolitical affairs.

Russia & Iran’s Nuclear Deal

In this connection I was struck by a report The Times of London carried July 13 under the headline, “Why is Putin pushing Tehran towards Trump’s nuclear deal?” “Russia is leaning on Iran,” Tom Parfitt reported, “to accept a deal that denies it the right to enrich uranium for any purpose.”

It is a good question, coming not quite a month after what we are now calling the Twelve–Day War against Iran.

Citing an earlier report in Axios, Parfitt noted, “Experts said that Moscow was probably pushing for a deal because it is wary of Iran disintegrating under renewed assault, which could threaten Russia’s economic interests.”

It was not clear at the time what Iran thought of Moscow’s advice on this point, but it seems plainer now: Iran is now preparing to reopen talks on its nuclear programs this Friday with Britain, France, and Germany, signatories to the accord the U.S. abandoned during Trump’s first term in 2018. This simply must be taken as an exploratory session to see if renewed talks with Washington may be possible.

Given that Iran is a BRICS member, and that Moscow and Tehran signed a wide-ranging strategic partnership last January, the questions raised are obvious. What are the BRICS and what are they not, or not yet? What do they expect of one another and what ought the rest of the world expect of them?

With its current membership, and excluding a dozen or so “partner countries,” BRICS members account for slightly more than 40 percent of the global population and a roughly similar proportion of global output as measured by purchasing power parity, known in the trade as PPP. Three of its members, China, India and Brazil, count among the world’s 10 largest economies.

O.K., but let’s note right off our frame of reference. This is a group whose shared interests are fundamentally economic as against strategic or geopolitical. This has been so from the first. The BRICS got their name indeed, from a Goldman Sachs economist who was specialized in middle-income nations, a.k.a. emerging markets.

Diverse Economic Models

When I first started thinking about the BRICS my mind went back to the old Non–Aligned Movement, those nations that coalesced around Zhou Enlai’s famous Five Principles — territorial integrity and sovereignty, nonaggression, non-interference in others’ internal affairs, cooperation for mutual benefit, peaceful coexistence — in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The NAM was fundamentally political in nature, fair to say, not economic. The BRICS share some of these values, but, by comparison, they have no politics — also fair to say.

This is a different time. The NAM was a response to the Cold War’s disruptive binaries. It reflected the aspiration common among its members, many of which were newly independent, for one or another variety of social democracy. A considerable role for the state in the development process, to take one example, was more or less a given.

You have a very diverse set of economic models among the BRICS, by contrast. There is one or another form of state capitalism — we can count China and Russia here — but none of its members is avowedly socialist. In addition, a lot of neoliberal ideology has flowed under the bridge since the old NAM days.

Michael Hudson, the superbly clarifying economist, had an hour-long interview the other day, also with Glenn Diesen, under the headline “The Economics of Civilizational Conflict.”

In it Hudson reminded us that BRICS members typically harbor well-developed capitalist elites, often educated in American institutions, often adherents of market-fundamentalist ideologies, and thoroughly invested in the neoliberal order.

Hudson, to speak personally, put an end to my nostalgia trip: It is no good reading into the BRICS things — intentions, purposes, determinations — that are simply not there. Global governance, the authority of international law, the New Development Bank, efforts to de-dollarize trade: Yes, yes, yes and yes. All good, all in the service, fundamentally, of each member’s national interest.

I see many good things coming from the BRICS as they proceed to contribute to the making of a new world order. But I do not see a “bloc,” however often those who know little about the group refer to it as one. I do not see a secretariat, or strategic alliances (as against partnerships), mutual defense pacts, much suggestion of mutual aid.

I am not waiting to hear from these nations that wonderful old word, “Solidarity,” or “solidaridad,” or “solidarité,” or whatever it is in any other language.

I am waiting for something else, yes, but I cannot tell you yet what it is. One must look forward, now, the past of little use as a guide.

This something else will make its appearance, best outcome: The direction of history suggests this. But there is little hint of it now, even among the non–Western nations.

Source: Consortium News.