The Supreme Court’s new term, which began last week, presents the court with a monumental opportunity to hand Donald Trump unbridled executive authority and eviscerate the separation of powers enshrined in the Constitution.

The court appears poised to rubber stamp many of Trump’s worst abuses, from the imposition of massive tariffs to seizing control of federal agencies created by Congress.

Although there are 39 cases on the court’s regular docket, it has already handled nearly 30 cases with temporary unsigned orders on its “emergency docket.” In those cases, the high court granted Trump’s requests to block orders from lower courts 20 times and ruled against his administration in only three cases; the others led to mixed rulings.

Even though the cases in which the high court has already opined are not final decisions on the merits, they provide a preview of what we can expect during this term after full briefing and oral arguments.

“It’s hard to imagine bigger tests of presidential power than these potentially once-in-a-century separation-of-powers battles,” Deepak Gupta, a lawyer who frequently appears before the court, told The New York Times. “And we’re seeing more than one of them at once.”

Here are some of the cases the court will use to establish the limits of executive power.

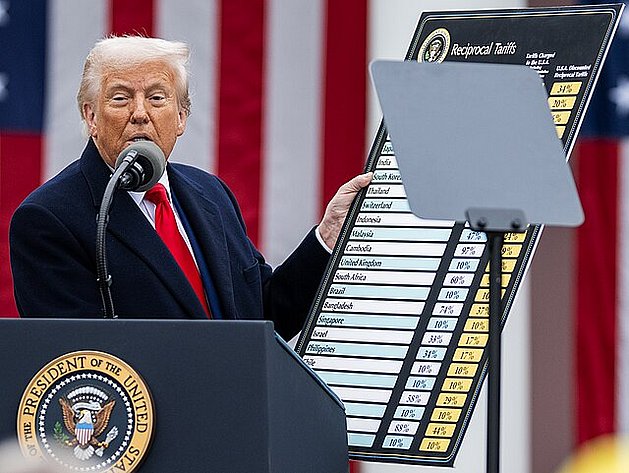

Trump with Reciprocal Tariff Chart in April.

Imposition of Massive Tariffs

In early November, the court will consider the legality of Trump’s wide-ranging tariffs on goods bought from other countries in two cases, Trump v. V.O.S. Selections and Learning Resources, Inc. v. Trump. The U.S. Court of Appeals held that Trump does not have the authority to unilaterally impose sweeping tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA).

Congress has the power to impose tariffs and taxes, and raise revenues under the Constitution. For most of U.S. history, tariffs provided the main source of financing for the federal government. In 1913, the 16th amendment was enacted to authorize “taxes on incomes.”

The IEEPA gives the president authority to deal with “any unusual or extraordinary threat” to U.S. national security, the economy, or foreign policy. The act doesn’t mention tariffs, taxes or duties but says the president can “regulate” the “importation” of “property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest.” Trump maintains that “regulate” implicitly includes the imposition of tariffs.

Trump’s lawyers argue that he didn’t impose tariffs to raise revenue but rather to “rectify America’s country-killing trade deficits and to stem the flood of fentanyl and other lethal drugs across our borders.”

In holding that Trump lacked the power to impose the tariffs, the Court of Appeals used the “major questions” doctrine, which requires that Congress provide clear guidance before a federal agency can proceed on a major question of political or economic significance.

The Supreme Court used the major questions doctrine to strike down vaccine, environmental, and student loan relief policies of the Biden administration.

These cases raise the issues of whether Congress delegated its tariff power to the president in the IEEPA and whether the president can increase taxes on the American people without a new act of Congress.

Firing Members of Agencies Created by Congress

The Supreme Court will also take up the issue of Trump’s authority to fire members of independent agencies in December. Trump v. Slaughter involves Trump’s removal of Rebecca Slaughter, a Democratic appointee to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

Congress prohibited the firing of FTC members unless they demonstrate “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” When the high court agreed to hear the case, it stayed a lower court decision ordering the Trump administration to reinstate Slaughter.

In this case, the high court will likely overrule its 1935 case of Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, in which it upheld a law that forbade the president from firing commissioners on the Federal Trade Commission absent a showing of good cause. The court ruled that Congress can limit the president’s authority to remove members of the FTC and other agencies that perform “quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial” functions.

On its emergency docket, the high court in Slaughter and two other cases temporarily blocked federal district court rulings that had prevented Trump from firing agency heads — of the FTC, the National Labor Relations Board, the Merit Systems Protection Board, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, and the Federal Trade Commission.

Trump’s argument that he should be able to remove agency heads for any reason is grounded in the “unitary executive” theory. Adherents to that theory believe that Article II of the Constitution establishes a

“hierarchical, unified executive department under the direct control of the President [who] alone possesses all of the executive power and … therefore can direct, control, and supervise inferior officers or agencies who seek to exercise discretionary executive power.”

In the 1988 case of Morrison v. Olson, the Supreme Court upheld a provision of the 1978 Ethics in Government Act, which was enacted in the wake of Watergate. It said that a special prosecutor could be removed by the president only for good cause.

This ruling was an implicit rejection of the unitary executive theory. Antonin Scalia maintained in dissent that the Constitution’s Article II Vesting Clause (which says, “The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States”) “does not mean some of the executive power, but all of the executive power.”

A majority of the members of the Supreme Court now subscribes to the unitary executive theory, which was once a marginal notion. In Trump v. Mazars, John Roberts wrote for the court that the president is “the only person who alone composes a branch of government,” an opinion he reiterated in Trump v. United States.

If the high court grants the president removal power over independent agencies, those agencies will no longer remain independent. The bodies that regulate our health, safety, labor, environment, and consumer products will be subject to political manipulation by the president.

Removing a Governor of the Federal Reserve Board

President Trump with Fed Chair Jerome Powell in July.

In January, the court will review Trump’s attempt to remove Lisa Cook, a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors who is serving a 14-year term. He tried to fire Cook for alleged mortgage fraud before she joined the board.

Under U.S. law, a Fed Board member who has been appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate can be removed only “for cause,” a term the law leaves undefined. Trump asserts that his allegations against Cook constitute sufficient cause.

A U.S. district court temporarily blocked Cook’s dismissal while her lawsuit makes its way through the courts. In Trump v. Cook, the Supreme Court delayed rendering a decision and scheduled the case for oral argument.

In this case, the court could decide whether Trump had cause for firing Cook and/or whether Congress has the authority to limit the removal of Federal Reserve Board governors.

Unlike other cases in which the Supreme Court allowed Trump’s firings of agency heads to occur even as the legal challenges proceed, the court allowed Cook to stay on the Fed Board pending the decision in her case. That may mean that the court will distinguish the Federal Reserve Board from other federal agencies, particularly in light of Trump’s repeated threats aimed at Fed Chair Jerome Powell.

Ending Birthright Citizenship

Although not yet on its calendar, the high court will likely review Trump’s January executive order purporting to end birthright citizenship.

Section 1 of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution says, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

In the 1898 landmark decision of United States v. Wong Kim Ark, the Supreme Court held that the 14th Amendment guarantees citizenship to virtually all individuals born in the U.S. with exceptions for children of foreign diplomats or enemy occupiers. Although the cases also excepted children in Indigenous tribes, Congress granted them citizenship in the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

Protesting deportation on International Human Rights Day, Minneapolis, 2017.

Trump’s executive order says that only children whose parents are U.S. citizens or permanent residents are U.S. citizens.

Lawsuits were filed in the states of Washington, Maryland and Massachusetts. In all three cases, federal district judges granted injunctions and blocked the operation of Trump’s order nationwide while the legal issue worked its way through the courts. The 1st, 4th, and 9th Circuit Courts of Appeals denied the Trump administration’s requests to stay the injunctions.

On Sept. 26, the Trump administration asked the Supreme Court to review the cases from the 1st and 9th Circuits that found Trump’s order on birthright citizenship to be unconstitutional. The high court will likely grant review of these cases.

Trump Fashioned a Court to Do His Bidding

Trump nominating Judge Amy Coney to Supreme Court, September 2020

By packing the court with three radical right-wingers during his first term, Trump fashioned a reactionary supermajority to do his bidding. Indeed, last year, in Trump v. United States the court held 6-3 that presidents have absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for core official acts, and presumptive immunity for all other official acts, while admitting that it is difficult to distinguish official from unofficial acts.

The Supreme Court may decide to review other cases, including Trump’s authority to deploy federal forces to U.S. cities, deport Venezuelans under the Alien Enemy Act of 1798, and refuse to spend funds appropriated by Congress.

As it did when cases testing Trump’s power came before it on the emergency docket, the high court will likely affirm most of his actions, underscoring the immunity it granted him last term, and ratifying his authoritarian program.

Source: Consortium News.