Nestled in the breathtaking mountains of the Himalayas, Ladakh is a remote but strategically important region of India that borders on China and Pakistan.

A vast place — larger than Switzerland — Ladakh is on the ancient Silk Road, with Kashmir to the West, Xinjiang to the North, Tibet to the East, and India to the south. It has been a crossroads of invasions and influences: including from Tibet, Mongolia, China, local princes, and Islam. At Indian independence it was absorbed by the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Ladakh bears the scars of the 1999, two-month Kargil War between India and Pakistan, a hard-fought Indian victory in which Delhi regained control of the Kargil district. It was a brief conflict that is etched deeply into India’s collective memory.

Yet beyond that, Ladakh’s stories are forgotten in the rest of the country until the sharp flare of border clashes with China thrusts it again into the headlines. For instance, it was the scene of widely reported hand-to- hand fighting with bricks and sticks between Indian and Chinese troops in 2020.

With an estimated population of 302,000, Ladakh is split between 46 percent mostly Shia Muslims, 40 percent Buddhist, and 10 percent Hindu. It has avoided the kind of communal violence that has plagued Muslim-Hindu relations elsewhere in India. In 2022, it peacefully resolved a four-decade-old dispute over building a Buddhist monastery in the Shia Muslim town of Kargil.

Ladakh’s geography makes it of crucial importance to the central government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. To put it directly under his government’s control, in 2019 Modi revoked the semi-autonomous status of the state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), separating Ladakh from J&K, to make them both union territories under a lieutenant governor appointed by Delhi. At the time there was huge international attention given to Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh was ignored.

But there is growing unrest in Ladakh as it challenges Modi.

The Buddhists at first welcomed separation from Jammu and Kashmir with which it was joined as a state in 1947. But as the realities of no longer being part of a state became clear, they reversed their stance, recognising their demands could only be achieved if they pulled together with the Shia Muslims of Ladakh to oppose the Modi government’s policies in their region.

Last month they protested together in Leh, Ladakh’s capital, over Ladakh’s future, including the key demand of statehood.

Protestors also want a second parliamentary seat from Kargil, as well as autonomy in governance, which the Indian Constitution grants to scheduled tribes. These are tribes recognised by the government because they have historically been excluded from social and economic opportunities. The creation of a commission to prioritise government jobs for local workers is another demand.

In addition, both the Muslim and Buddhist communities seek legal safeguards and more control over land acquisition to block large corporations, often favoured by Modi and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), from harming the environment, glaciers, grazing grounds and local communities. Before the change of status to territory in 2019, Ladakh was protected from outsiders buying land or applying for jobs.

The government claims there’s no resource exploitation in Ladakh and that development will be carbon-neutral and based on community consent.

Modi’s government crushed a protest for these demands on Sept. 24, leaving four dead, many injured — including more than 30 security personnel — and numerous demonstrators arrested. Protestors set fire to the local office of Modi’s BJP party. On Oct. 17 the central government agreed to a judicial investigation into the protestors’ deaths.

Kavinder Gupta, Ladakh’s lieutenant governor, blamed the unrest on youth trying to emulate the September uprising in Nepal — the so-called Gen Z protest — that brought down the government there.

Negotiating With Delhi

Ladakh

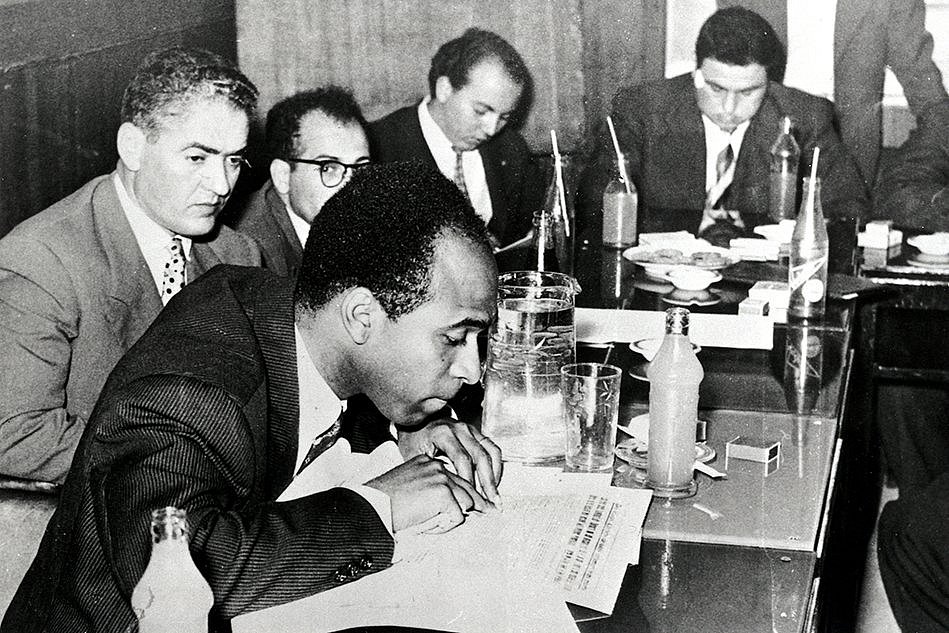

Sajjad Kargili, a Ladakh leader, has been in the forefront of the region’s interactions with the central government over their demands.

Kargili is seen as politically savvy yet remarkably free from cynicism. The people he represents see him as driven by genuine concern for the region’s mostly tribal population: apricot growers, farmers, animal rearers, craftsmen, many of whom are poor and struggling as well as the small businessmen and hoteliers who sustain this tourist magnet.

For years, Kargili has not only drawn national attention to Ladakh’s major challenges — its struggle for statehood, deep poverty, and high unemployment — but also everyday problems: gaps in governance, student hardships, water shortages, lack of infrastructure, and the harsh isolation of months buried in snow. He has harnessed social media to share the cultural heritage and ethnic and linguistic diversity of this secluded corner of India.

Kargili helped bring about the peaceful end to the tensions over the Buddhist monastery that had threatened to disrupt a fragile peace between Buddhists and Muslims in his Himalayan homeland.

He played a key role in fostering consensus within the Muslim community and facilitating dialogue with the Buddhists to help resolve that dispute. He negotiated as the political head of Jamiat Ul Ulama Isna Asharia Kargil, a religious and socio-political organization of Ladakh’s Muslim community, which he represents in the Kargil Democratic Alliance, a coalition of social, political, and religious groups in Ladakh.

“It wasn’t just me — it was a collective effort by everyone,” said Kargili. In a world where taking credit is currency, it’s rare to see someone deflect praise.

Kargili is one of the key negotiators in discussions with the central government over the region’s many issues with Delhi. He was in Delhi to press for the probe into the killing of the protestors.

Kargili is seen as a leader among those Ladakhis who remain unwavering in their calls against Delhi for greater autonomy, political representation, constitutional protections and sustained public attention despite the central government’s crackdown and right-wing attempts to brand the protests as anti-national.

Ladakh

Married to a woman from the Balti tribe, the 42-year-old Kargili, who is from the Shina tribe, told Consortium News:

“India is the largest democracy in the world and we want to be part of it through a legislature. We want a voice. We don’t want to be governed by a bureaucrat who is not elected or accountable to our people. Our diversity has been neglected. Our federal structure has been badly affected. There is no consent from the people of Ladakh when they impose policies.”

Kargili emerged as a leader in the wake of the 2019 upheaval that saw Ladakh separated from Jammu and Kashmir and both losing statehood. Ladakh is still often grouped in the Indian public mind with Jammu and Kashmir — a region beset by an insurgency supported by Pakistan. Kargili has been keen to emphasise the differences between the two with their distinct histories, geographies, and challenges.

While the Modi government allowed for elections in J&K and local legislators in 2024, Ladakh is represented in Delhi by only one parliamentary member elected from the city of Leh. With no local legislators, governance falls to two hill councils — statutory bodies with locally elected members — one each for Leh and Kargil. These councils plan and implement policy under the supervision of the lieutenant governor.

Alienating Buddhists

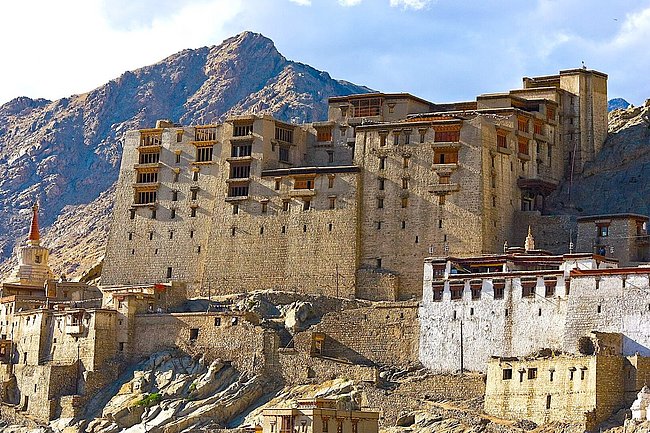

The Leh Palace, also known as Lachen Palkar Palace, is a former royal palace overlooking the city of Leh in Ladakh, India.

Buddhists primarily reside in Leh, situated at 11,000 feet above sea level and about 200 kilometres from Kargil, which lies at 8,780 feet and is predominantly home to Shia Muslims. The ayatollahs from Iran hold symbolic influence in Kargil.

This religious connection has sometimes been cynically used by some Hindu nationalists to question the loyalty of Shia Muslims. Now, even the Buddhist community is being painted with the same broad and unjust brush.

Like in many other regions where it once had minimal influence, the BJP, under Modi, has established itself in Ladakh over the past decade, securing victories in the 2014 and 2019 general elections.

The BJP’s attempt to fuel communal divisions in the remote Himalayan region — a typical modus operandi of the BJP to gain political ground — ultimately failed. In 2024, an independent candidate, who is a Shia Muslim, defeated the BJP contender for the sole seat in Parliament.

Whatever remained of the BJP’s credibility among Ladakhi Buddhists was shattered when the Modi government arrested Sonam Wangchuk, the face of the movement, on Sept. 26. This Buddhist engineer and environmentalist became a household name in India after he inspired the character played by Aamir Khan in 3 Idiots (2009), one of Bollywood’s most beloved coming-of-age films.

Wangchuk, who also reversed his stance on the government’s 2019 move to bring Ladakh under Delhi’s control, has been arrested under India’s stringent counter-terrorism law, which makes obtaining bail extremely difficult and often results in individuals being imprisoned for years without trial.

Over the past decade, the government has increasingly relied on this tactic to suppress dissent and target dissenters, amid a marked decline in civil liberties and press freedom and a troubling rise in Islamophobia.

Straddling the line between activist and politician, Kargili attempts to navigate the difficult path of raising issues and denouncing religious bigotry, all the while maintaining the ability to work with the local administration and engage with the Modi government.

This hard-earned influence has earned him a place among the six negotiators speaking with Home Minister Amit Shah on critical issues concerning Ladakh’s future.

“Our core belief is dialogue, but dialogue must not happen for the sake of dialogue. Dialogue must be fruitful and productive,” Kargili said in an interview. “Our issues are pending. People are fed up. We are now protesting out of frustration.”

Against the Odds

Sajjad Kargili leading a protest in Kargil on Aug. 11, 2025.

Kargili was a 37-year-old journalist when he first ran for parliament in 2018, narrowly losing by just 8,000 votes. At the time, his candidacy was a spontaneous decision, but the close result inspired him to pursue a political path. In 2024, he faced a painful setback, withdrawing from the race due to political challenges and personal reasons, as his wife was seriously ill.

Coming from a middle class family, his father would have preferred that he pursue a steady job, lead a settled life, and earn a comfortable living.

Kargili, however, felt compelled to work with others to raise social issues. After a few months of recovery from the setback of his failed 2024 run, he got back to work.

On the day earlier this month that he spoke to Consortium News, he was fielding calls from a father seeking help to find his daughter a job, visiting jailed protesters in Leh, and tweeting that they, like Wangchuk, also deserve the public’s attention.

“Elections are not larger than the movement,” he said. “I thought what has happened should not have happened, but ups and downs are a part of life. Right now, we feel that our existence is in danger, we feel insecure, not having safeguards for our glaciers, our environment and not having democracy in the region.”

He is not concerned only with Ladakh’s local issues. Kargili has also joined protests against a controversial citizenship law that worried Muslims, and against human rights violations in Manipur and Chhattisgarh, advocating for communal harmony.

Over 1,000 kilometres from home and 500 from Delhi, Kargili found himself on Oct. 7 in Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, governed by a BJP hardliner known for suppressing dissent, especially from Muslims.

At the press club not far from the chief minister’s office, he spoke to a small crowd about the demands of the Ladakhi people, condemning Wangchuk’s arrest and the wider crackdown on rights and freedoms.

From Lucknow, Kargili travelled 100 kilometres west to Kanpur, once a thriving industrial hub known as the “Manchester of the East,” now overcrowded and blighted by garbage and pollution from leather tanneries and dye factories.

Invited by a lone activist, he spoke to an even smaller gathering.

“I’m a from a remote area and at this tough time when we are struggling for our identity and fighting for our rights, every single person who is raising our voice is important,” said Kargili. “If they are peace loving and Gandhian, as one of the representatives of Ladakh, it is my responsibility to accept their invitation, whether the gathering is big or small.”

Certainly the task of overcoming Modi and winning back statehood is a big task. Without much leverage, it will take that kind of painstaking organizing and sustained protest for the people of Ladakh to stand a chance.

Source: Consortium News.