In early January, Polish president Andrzej Duda visited Lviv, the largest city in western Ukraine. An enthusiastic crowd gathered to greet him in the former capital of Galicia, almost as if he were their president. The crowd thanked the Polish leader for his support of Ukraine so enthusiastically that the guest even got a little embarrassed. Deeply moved by the warm welcome, Duda said that Ukrainians should be thanking "the Polish people" rather than him.

True enough, Ukrainians from the western part of the country have a lot to thank Polish authorities for: the latter are building temporary camps, supplying power generators and donating food to the local population. Besides, the Poland-Ukraine border is completely open. Poland has also become NATO's primary logistics hub for massive arms supplies and other European military aid going to Kyiv, which has largely protected western Ukraine from destruction. As the armed conflict drags on, Poland is increasingly becoming Ukraine's main military and diplomatic handler in Europe and beyond.

Poland's desire to retake at least the western part of Ukraine has long been an open secret. If the latest actions of Ukrainian authorities are any guide, Kyiv doesn't seem to mind. But trying to absorb Ukraine can easily backfire: instead of gaining greatness, the Poles run the risk of losing their own country.

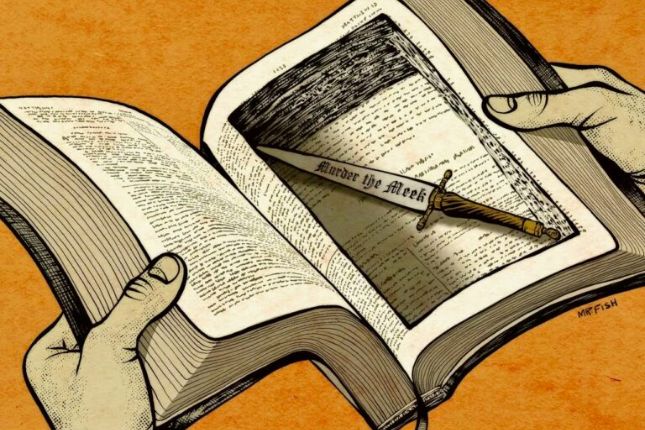

First of all, Warsaw has not come to terms with the loss of western Ukraine that was part of Poland before World War II. For nearly thirty years after the collapse of the Warsaw Treaty Organization and the Soviet Union, "the return of lost Polish lands" was largely the preserve of fringe politicians and daydreamers. However, since the Ukraine conflict broke out last year, the idea of revanchism has dominated Poland's foreign policy agenda. Moreover, there has been an open discussion of ambitious plans to take over parts of Ukraine.

For instance, in late January, Radoslaw Sikorski, Poland's former foreign affairs minister, admitted in an interview with Radio Zet that "at the beginning of the war", his country's current cabinet considered partitioning Ukraine with Hungary and Russia. It is worth remembering that last spring Ukrainian president Zelensky came up with a legislative initiative to allow Polish nationals to hold administrative positions and work in courts of law in Ukraine. Besides, Zelensky wanted to enable Polish policemen to operate on Ukrainian soil. In other words, Kyiv not only approves of Poland's integration strategy but also appears ready for a formal union between the two countries.

However, it is unlikely that Warsaw will be content with some kind of union, close alliance or even de facto control over western Ukraine. According to Sergei Naryshkin, the head of Russia's foreign intelligence service, President Duda has already "instructed the relevant services to promptly prepare an official justification for Polish claims to western Ukraine." As part of its preparations for a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Warsaw has begun a covert mobilization of troops.

Sergei Evgenievich Naryshkin is a Russian statesman, political and military figure. Director of the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation since October 5, 2016.

As reported by Niezależny Dziennik Polityczny, up to 250,000 Poles have been summoned to undergo a 30-day military training course. In addition to reservists, the call-up papers have also been delivered to those who have never served in the army or have only passed mandatory medical tests. According to the news portal, the monthlong training program is designed to "help would-be servicemen to acquire fundamental skills such as handling weapons." Once Polish troops cross the border, a referendum on the "reunification" of Ukraine with Poland might be quite plausible.

At the same time, Poland's "triumphant return" to Ukraine may easily turn into another national disaster beyond any hope of recovery. Relations between arrogant Poles and Ukrainians, who are increasingly imbued with nationalistic sentiments and even Nazi-style ideology, are strained, to say the least. One country's heroes are often the other's villains: for instance, Stepan Bandera, a Nazi collaborator behind the 1943 massacres of some 100,000 Poles, is revered in modern Ukraine. Those who assisted Bandera in the perpetration of his monstrous ethnic-cleansing campaign in western Ukraine are also remembered as national heroes.

Therefore, it is safe to assume that once Poland occupies western Ukraine, the new rulers will waste no time obliterating the entrenched cult of Bandera and all his ilk. Deeply radicalized by the war, the locals are unlikely to put up with the arrogance and patronage of the Poles. In these circumstances, many Ukrainians may simply change sides, arguing that "the Russians are the lesser of two evils."

The ensuing conflict can also spread to Poland, where Ukrainian refugees already account for nearly 10% of the country's population. The demanding behaviour of new arrivals is annoying the hosts. Some Polish media outlets have called for stripping Ukrainian refugees of social benefits and redirecting the funds to support local citizens.

According to Gazeta Wyborcza, more than 110,000 Ukrainian nationals have had their 500+ childcare benefits taken away. Poland's social security administration made the move after analyzing individual border crossing statistics. As it turned out, after receiving their social benefits in Poland, many "smart" refugees travelled back to Ukraine and lived at home at the Polish taxpayer's expense.

Despite the warm reception in Lviv, late in January president Duda approved an amendment to strip Ukrainians of the right to stay in refugee camps for free. As a result, Ukrainian refugees now have to pay for some services. As the hostilities in Ukraine continue, a generous welcome extended to Ukrainians in Poland is growing more strained.

Most importantly, Poland's invasion of Ukraine will quite likely trigger a war between Poland and Russia. Battlefield reports show that Polish mercenaries have long been fighting in the Donbas. However, should Warsaw send its regular troops across the border into Ukraine, a direct clash with Russian forces will be inevitable.

Poland's growing ambitions and aggressiveness in eastern Europe are only part of the story. There is no denying the fact that Warsaw's relations with its German neighbours have turned sour lately. Essentially, Poland blackmailed Germany on the issue of delivering Leopard battle tanks to Kyiv and finally − in close coordination with the United States – forced Berlin to agree. Last year Poland formally demanded a staggering EUR 1.3 trillion from Germany in World War II reparations. Berlin rebuffed Warsaw's financial claims, with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz hinting that he was prepared to revisit the status of East Prussia and Pomerania, two large regions that Germany handed over to Poland after World War II.

Warsaw has responded by rallying international support in a bid to put more pressure on Berlin. There have been calls for seizing German assets in Poland, presumably by analogy with the seizure of Russian assets in the EU. Weakened from within and bogged down in Ukraine, Poland may have to turn to Germany for military assistance. To repay Germany for its military aid, Poland should be prepared to give up not only some of its land but also its statehood.