The rapid expansion of the Pine Gap satellite surveillance base near Alice Springs, Australia from 35 to 45 satellite dishes, is designed to give the U.S. the edge in a potential nuclear war with China.

Where desert oaks and spinifex tufts once baked in the Central Australian sun, three new white domes have mushroomed in a 14 hectare clearing along the western edge of the U.S.’ “most important surveillance base” in the world.

Under huge plastic radomes, three of Pine Gap’s new satellite dishes have been built to receive information from a new generation of U.S. spy satellites that bring a heightened level of surveillance of China’s nuclear missile launch sites at a time of increasing confrontation between China and the U.S. and its allies.

Thermal imaging satellites presently used by the Pine Gap base are able to detect rocket and missile launches in the battlefields of Gaza and Ukraine, as I have earlier reported, but the greatest interest of the new satellite dishes at the base are missile launches from China.

A new generation of “eyes-in-the-sky,” known as Overhead Persistent InfraRed (OPIR) satellites, will soon be launched by the U.S. military to augment the existing satellites of the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS). These satellites are designed to detect the thermal signatures of rocket and missile launches, using immensely sensitive infra-red sensors.

The Rush to Catch Up

The U.S. Defense Department’s “Space Force” is poised to launch five new ballistic missile early warning infra-red sensor tracking satellites. The first launch had been planned for 2025, but technical difficulties have seen it delayed until 2026. Three of the five new OPIR satellites will go into geostationary orbit at 35,000 kms altitude over the equator, and two will orbit the poles.

The new Pine Gap dishes will use these OPIR satellites acting as “spotters” to better detect heat signatures from ballistic missiles at the earliest stages of launch, to then send this data to low orbit tracking satellites which aim then to guide the targeting of the launch locations and of the incoming missiles.

They will aim to defeat the latest hi-tech manoeuvrable ballistic and hypersonic missiles which have been developed by China and Russia. As Declassified Australia reported in depth in 2022, the U.S. has no present infallible defence against hypersonic missiles, which can reach speeds of 12,500 kph and carry either conventional or nuclear warheads.

It became evident to U.S. military planners that the older Space-Based Infrared System satellites were not up to dealing with the advanced hypersonic missiles — developing new surveillance satellites therefore became urgent. As the new satellites were being developed to face the new hypersonic threat, new satellite dishes and electronics on the ground were also needed. That’s why they need to upgrade Pine Gap.

Satellite constructor Northrop Grumman’s vice president of OPIR and Geospatial Systems said, “What we want to make sure of is that as threats evolve and as hypersonic missiles come onboard, we are able to evolve our capability.”

So Begins the New Arms Race

A Kh-47M2 Kinzhal being carried by a Mikoyan MiG-31K interceptor on display in 2018 Moscow Victory Day Parades. (Kremlin.ru, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

U.S. planning to counter new generation hypersonic missiles gained impetus when in 2017 Russia announced their nuclear capable hypersonic aero-ballistic air-to-surface missile, the Kh-47M2 Kinzhal. These missiles saw their first use in a battlefield when Russia fired two into western Ukraine in March 2022.

China began testing its DF-ZF hypersonic glide missile in 2013. Missile defence experts had predicted it would not be able to be deployed until at least 2036, but China introduced the DF-ZF into service in 2020.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has been rushing to develop its own hypersonic missiles. The Pentagon’s 2025 budget request for hypersonic research is U.S.$6.9 billion, up from U.S.$4.7 billion in 2023.

Australia’s Defence Department allocated $9.3-billion in 2020 for high-speed long-range strike and missile defence including for hypersonic development, test and evaluation. Development of hypersonic technology with the U.S. has also been made a priority in 2023 under Pillar Two of the controversial AUKU.S. military agreement.

The accelerating arms race in hypersonic missiles and anti-hypersonic defensive technology was unleashed upon the world following the U.S. unilateral decision in 2002 under George W. Bush to withdraw from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty between the Soviet Union and U.S.

The ensuing weapons competition has pushed aside risk-mitigation measures, such as expanding the New START nuclear arms reduction treaty, negotiating new multilateral arms control agreements, undertaking transparency and confidence-building measures, and puts in jeopardy a cornerstone of world peace, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Amplifying Risk of Nuclear War

Chinese DF-17 glider launcher on exhibit in Beijing in 2022. (Yiyuanju, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The OPIR infrared detection satellites that Pine Gap will soon be using, will detect missile launches far more rapidly and accurately than at present, allowing more reliable U.S. targeting of launch locations and potentially in-flight missiles. The aim would be to reduce retaliatory strikes by China should such a nuclear war be started.

This ability may encourage the U.S. military planners to think they could win a nuclear war, if they think they could destroy most of China’s nuclear missiles.

This may sound good to them, but it has an immense downside. It may increase the likelihood of China, if it feels existentially threatened, making its first nuclear response its biggest, because it may not have a chance for a second. Escalation from a limited nuclear exchange may rapidly spin out of control.

Unlike the U.S.A’s most recent Nuclear Posture Review which asserted its right to a “first nuclear strike” in “extreme circumstances,” China has a “no first strike” nuclear weapon policy.

However there are indications that China has upped its nuclear attack defence preparations, by moving to a launch-on-warning (LOW) posture.

This LOW defence posture involves China relying on space and ground sensors to give early warning of an attack, to allow a counter-attack before its defences are destroyed.

One of Australia’s leading researchers on Pine Gap has been at the ANU’s Centre for Strategic and International Studies, the late Professor Des Ball. In an interview before he died he saw U.S. surveillance bases like Pine Gap as particularly vulnerable in a potential nuclear conflict with China.

“There is no way that the Chinese can win… unless they take out command and control systems, unless they can degrade the surveillance capabilities that link the sensors with the aircraft carriers for example.”

“That’s the very first step, to make those American platforms blind, deaf and dumb. It’s the only way that those relatively primitive Chinese capabilities would have any hope against American carrier battle groups.”

Though rarely in the public consciousness, the prospect of the U.S. base at Pine Gap being targeted early in any conflict between the U.S.A and China is high.

A secret intelligence assessment reported in the Defence Department’s 2009 Force Posture Review made clear the official view:

“Defence [Department] thinking is that in the event of a conflict with the United States, China would attempt to destroy Pine Gap.”

Professor Richard Tanter, Australia’s key Pine Gap researcher, has pointed out China’s targeting of Pine Gap in a potential conflict involving the U.S., due in great part to the base’s use of infra-red detection satellites to monitor Chinese missile launches:

“Pine Gap… remains a likely priority target for a Chinese missile strike in the event of a major China-United States conflict, both because of its role as a remote ground station for early warning satellites in the Defence Support Program and Space Based Infra Red Satellite systems, and its larger role as a command, control, downlink, and processing facility for U.S. signals intelligence satellites in geo-stationary orbit.”

Alice Springs, Australia, 2005. (Johannes Püller, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Updated details on the capabilities of the satellite radomes of Pine Gap have been published in March by Prof Tanter and Bill Robinson, for the Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability.

Paul Dibb, a former head of Defence intelligence and now a respected senior defence strategist, is even more certain. He now states that in a war between the U.S.A and China, Pine Gap will be China’s most important early nuclear target:

“[This is] because of its ability to give the U.S. instant, real-time warning of a Chinese nuclear attack, the precise number of missiles, their trajectory and their likely targets.”

There are other surveillance and communication bases in Australia used by the U.S. that are also most likely to be targeted in a nuclear exchange. These are the surveillance and communication bases at Kojarina near Geraldton and at North West Cape near Exmouth — some also suggest the new U.S. AirForce B-52 nuclear bomber squadron base under-construction in Darwin will join these, as the four prime Australian targets in any war-planning by China.

Bringing the Risk Back Home

In an environment of threat and escalation, of fear and suspicion, the prospect of war breaking out between the U.S. and China could rise rapidly to the point of a counter-strike by China on U.S. assets in Australia.

A hypersonic nuclear missile, if fired at Pine Gap from a Chinese submarine in international waters off the west coast, flying at up to 15,000 km/h, would reach its target in a matter of a few minutes from launch.

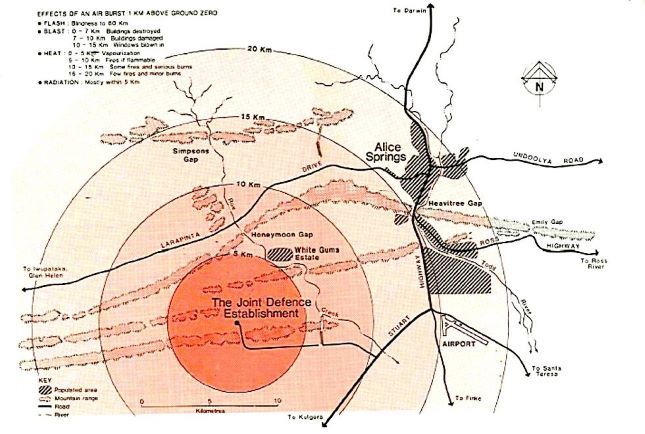

The direct effects of a nuclear weapon attack on the Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap are estimated to extend to Alice Springs. This was the conclusion of a 1985 report, prepared by a medical doctor, titled “What will happen to Alice when the bomb goes off?” Some may think that’s a fair question to ask today. (Image from Medical Association for the Prevention of War; Sourced R Tanter)

A nuclear ground blast at Pine Gap would cause a gigantic cloud of super-heated dust and earth to rapidly rise above the destroyed base. The dust from this huge mushroom cloud would contaminate huge expanses of the Australian inland, and would likely spread for thousands of kilometres.

A local Alice Springs doctor, concerned at the lack of emergency medical preparations by the town’s hospital and the lack of emergency evacuation plans by local authorities in the case of a nuclear war, prepared a report in 1985 for the Medical Association for the Prevention of War.

At the time of preparing his report, the Cold War was in its last desperate stages and the very real threat to the American base then was if a nuclear broke out between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

The doctor, using research done at the time by Prof Des Ball and others, assessed the catastrophic effects that a nuclear attack on the Pine Gap base would have on his town and its population.

His conclusions are worth bearing in mind today in responding to the acknowledged risks of hosting U.S. bases.

“If on the day [of a nuclear strike] it was blowing from anywhere in the southwest quarter, Alice Springs would be enveloped in the plume of radiation at greater than the lethal dose,” he wrote.

“Most people not evacuated within one hour would receive fatal radiation doses.”

Main Photo: Under construction in July 2021 at the U.S. satellite surveillance base at Pine Gap — in this previously unpublished photograph, we get a rare glimpse of one of the new OPIR satellite dishes seen inside the partially completed radome, at upper left. The top half of the dome can be seen resting beside the open radome on the ground, with two cranes visible ready to lift the top half into place. The white 4WD vehicle on the road near one of the cranes gives an indication of scale. (Declassified Australia’s original image: Maxar Technologies; Google Earth)

Source: Consotrium News