For all the feigned sympathy of the European Union towards Ukraine and Ukrainians amid their conflict with Russia, European politicians are beginning to feel concerned that contacts between European and Ukrainian neo-Nazis and their "brotherhood-in-arms" may spell trouble for Europe.

According to the June 14, 2023 Europol report, most of Europe's far-right movements have supported Ukraine, or, more precisely, their "ideological colleagues" from Azov, a Ukrainian neo-Nazi paramilitary outfit. Increasingly, calls have been circulating among the West's neo-Nazis to enlist in Azov and join the fighting in Ukraine.

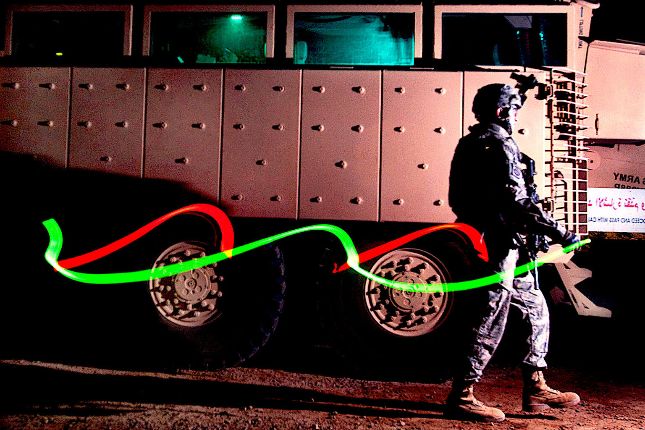

Europol believes that the forays Europe's ultra-right "legionnaires" have been making to the conflict zone, and, more importantly, their direct participation in the hostilities can further radicalize them, both ideologically and by way of prompting them to commit actual acts of terror. For the far-right militants, national interests are not a top priority, as opposed to their racist white supremacy ideas. As Mikael Skillt, a Swedish neo-Nazi and Azov volunteer, once happily observed, "right-wing ideology is the basis of everything. I can give you this example: there is not a single Negro among the fighters".

EU authorities fear that, having used the war between Ukraine and Russia as "a training ground", Europe's idea-driven mercenaries will come back home and "fan the fire" in their home countries. Sober-minded politicians in Germany, for example, have repeatedly pointed to Chancellor Olaf Scholz and other leaders of the ruling Social Democratic Party to a potential danger of providing money and weapons to support Ukrainian neo-Nazis.

The success story of the neo-Nazi Azov group in Ukrainian politics, with its extensive network of affiliated organizations, including teenage and children's outfits, is an impressive model European right-wing radicals are keen to emulate while actively sharing each other's experiences in the realm of ideas.

Among the "philosophical pillars" of Azov's neo-Nazi ideology are the writings of Ukrainian Nazism theorist Dmytro Dontsov who thus wrote back in the 1920s: "fully aware of its historical mission to protect its ancient culture from Muscovites' Asian barbarism, Ukraine has always been Russia's open enemy, and in pursuit of its liberation aspirations, it has always sought help from the West, especially, from the Germans."

As is often the case with such ideologues, his theory is a thick mixture of dark romanticism and cruel neo-mythological fairy tales. Dontsov based his racist constructs on the German-Scandinavian pagan myth of Ragnarök, mankind's final battle, that would lead to the death of this world, only to give rise to its rebirth later.

Azov also borrowed symbolism from Nazi quasi-pagan cults, including Wolfsangel, the "wolf's hook", variations of the swastika, and runic symbols. This brings Ukrainian ultra-right closer to their German counterparts and helps build some kind of "kinship" between them.

Ukrainian Nazis also have something in common with Italian neo-fascists. Azov's leaders who had traveled to Italy on their "internship trips", adopted their CasaPound ("House of Pound") movement's take on building a "state within a state" through a pervasive network of social movements, including children's summer camps offering "patriotic military education" and nursing services for the elderly.

To strengthen their "international relations," Ukrainian neo-Nazis set up an organization they called the "Reconquista." In Ukraine, its activities have been overseen by Olena Semenyaka, the international secretary of the National Corps party.

The aim of the "Reconquista" is to bring onboard neo-Nazi "legionnaires" from Europe and the United States who would be ready and willing to share their combat experience or, at the very least, prepared to fight alongside Azov fighters. In addition, Azov's "diplomats" were supposed to negotiate with their European "sympathizers" to attract funding needed to finance Ukraine's ultra-right. The "Reconquista" has been active ever since the Euromaidan protests of 2013 and 2014, and succeeded in establishing close and friendly ties with CasaPound and with a German neo-Nazi organization Der Dritte Weg ("The Third Way").

Members of the "Third Way" are what one might call the right's right. They are far more extreme than the right-wing parliamentary party Alternative for Germany (which used to be considered marginal, but in 2023, according to German polls, came in second in popularity among the voters). Some of Der Dritte Weg's figures have either become Azov volunteers, or are helping financially, while still others introduce Ukrainians to their "colleagues" from other European far-right organizations: Swedish, Norwegian, French, Croatian, and Polish.

In the meantime, the United States, who is Europe's "senior partner", seems to be unperturbed by the "second coming" of nationalism to European countries and the ultra-right nationalists' scurry around Ukraine as the European nationalists have never been viewed as an existential threat to the United States.

On the contrary, the first US historical foray into Europe at the end of World War I was marked by the emergence of "Wilson's Europe," seeing the supranational empires (such as the Russian Empire, Austria-Hungary, and Germany) being replaced by a whole scattering of sovereign nation-states. Quite soon, however, these states, abandoned the democratic parliamentary model of government suggested to them and actually turned into ethnocracies, authoritarian nationalist regimes of a semi-fascist ilk, hating one another with a passion.

The Eastern Europe of the mid-1930s was, by and large, a product of US strategy in Europe.

The "divide and rule" principle was not invented in our time, nor is it a brainchild of the US. That said, the US seems to be quite an adherent of this practice that includes encouraging "international friendship" of the ultra-right from all corners of the EU with Ukraine's radicals. It is quite telling that the EU leadership and Europol, albeit somewhat belatedly, have finally noted a potential danger of this tactic and started sounding the alarm.