In Germany, the GDP began to fall earlier than in the eurozone as a whole and months before the recession in the US, where it began only in the second half of the year. Some observers attribute the recession to a spike in energy prices. Others point to completely different factors. What is really going on?

Recession: The Russians did it?

The data for the first quarter of 2023 shows that the German GDP fell by 0.3%. The last quarter of 2022 saw an even bigger drop, of 0.5%. Two consecutive quarters of decline is a recession.

Considering that the German economy makes up 30% of the EU economy, many expect it to play the role of a gorged canary in the proverbial coal mine. And the Germans themselves have no doubt that their recession is largely due to the war in Ukraine, and more specifically to the energy problems arising from the sanctions against Russia.

What is the main problem? Yes, the sanctions led to well-known problems for Rosneft Deutschland GmbH, which operates four refineries in Germany with a total capacity of 23.2 million tons, but nothing too catastrophic happened. There were no refinery shutdowns, and the supplies that previously came from Russia started coming from elsewhere.

It was a completely different story with gas from Russia: At first the rate rose to a few thousand dollars per 1,000 cubic meters, so German consumers, both industrial and ordinary citizens, dropped their gas consumption to dozens of percentage points below what it was before the war in Ukraine. It would seem that, indeed, this should have hurt the German economy. In fact, back in the spring of 2022, the Bundesbank was reading the writing on the wall aloud: "Ban on Russian gas would plunge Germany into recession, warns the Bundesbank." But is it true?

The fact is that peak German gas bills fell in the first three quarters of 2022, when Europe was filling up its storage facilities. And the recession began in the fourth quarter – when Europe's gas purchases plummeted and prices began to collapse. Today, they are four times lower than they were last summer.

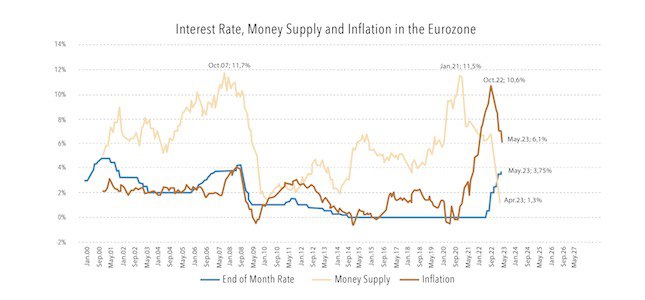

There are other reasons to doubt that the gas affair was to blame for the recession. The money supply in Germany was rising until October 2022 – something that typically means no recession. The M2 only began to fall in November of last year, when gas purchases almost stopped. And the decline is ongoing.

A number of observers are trying to attribute the recession on German soil to the "thriftiness" of German consumers, but this contradicts the fundamentals of economics: A society with significantly less money cannot help but experience a decline in consumer demand.

The first step toward a European recession?

Germany is the EU's largest exporter, but most of its exports simply go to the rest of the EU-27. Its recession is largely caused by the decline in new export orders that began late last year. Consequently, it is highly likely that the recession, having started in Germany, will soon become a fact for the EU as a whole. In other words, this is not shaping up to be a strictly German story, but rather a story of the canary in the coal mine.

Euro Area Manufacturing PMI.

All the signs that the recession will spread throughout Europe are already there. The Purchasing Managers' Index for eurozone manufacturers is below 45. It noticeably hit this level or lower two times in the twenty-first century, in 2008-2009 and 2020.

Of course, the Purchasing Managers' Index in services, the source of the bulk of the GDP of modern economies, is still above 50 (growth zone), but as we know from past crises, there is simply a lag: The Services PMI falls about 6 to 12 months after the Manufacturing PMI.

Thus, it is only a matter of time: A recession in Europe itself is a done deal.

What are the causes and where is the solution?

The key parameter for real (i.e., already inflation-adjusted) demand in the normal economy is whether t the money supply (M2) is growing faster than inflation. As seen in the chart above, since October 2022, M2 has been growing slower than inflation throughout the eurozone. This should mean a recession in the EU as a whole, with a lag of 6 to 12 months – no later than October 2023. History knows examples when the lag exceeded 12 months (the lag reached a record 14 months in the US in the early 1980s), but these are rather rare.

The reason for the contraction of the money supply in the modern economy was described by Milton Friedman in his famous Friedman's k-percent rule. Central banks normally try not to interfere with the volume of the money supply outside of overt and acute crises. Naturally, this limits the monetary base during non-crisis periods. As a result, the growing economy faces a gradual exhaustion of the money available to it. As soon as banks reduce lending – which happens anytime they seem to have a reason to be cautious – the bank multiplier falls, and the money supply with it.

Friedman noted that to avoid this situation, central banks – in addition to private banks – should add money to the economy every year. This would prevent the money supply from falling behind GDP growth, and the crises themselves would lose their severity. But no modern central bank, with the exception of China, implements this policy, thus none of the world's major economies – except, of course, China – experience uninterrupted economic growth.

Understanding the cause, we can easily imagine how the eurozone could come out of the recession that will inevitably begin in the second half of 2023. This could happen if the European Central Bank would decide to increase the monetary base of the eurozone, for example, by buying the government bonds of European countries, or by substantially lowering the discount rate.

The second scenario is unimaginable in the near future: As long as inflation remains at today's level, modern central banks will not seriously reduce the rate. The first scenario could technically be implemented even today, thereby completely preventing a recession. But, as noted above, in practice, modern central banks normally start expanding the money supply only after a crisis has begun and turned into recession – that is, after a couple of quarters of recession. In the European context, this would be no earlier than early 2024.

A faster response is possible only if European economic authorities are impressed by the example of the active countercyclical policies of the US Federal Reserve, as they were in 2008-2009, following the brilliant example of Ben Bernanke, who launched a monetary expansion in the United States immediately after the recession began.

However, such a response is unlikely in 2023. Bernanke worked in an environment of low inflation and even deflation in 2008. Today both the US and the EU are in fundamentally different conditions. Inflation is above the discount rate and will not drop below on its own in the near future. Nor do Europe or the US seem to have any intention of raising the discount rate above inflation themselves this summer. Hence, Bernanke's "situation" is unlikely to be reproduced under current conditions.

The most likely scenario is that in late 2023 and 2024, the European economic authorities, having waited for a slowdown in inflation due to the recession, will start a monetary expansion. But, as a result, the eurozone GDP will first experience a two to three-quarter recession and only then begin to recover.