Only five people attended the traditional photo shoot prior to the G20 summit in Bali. They were Indonesia's President Joko Widodo, Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, South Korea's President Yun Seok Yol, and Australia's Prime Minister Anthony Albanez. The president of the International Olympic Committee, Thomas Bach, was also present at the meeting, apparently for the benefit of the company. There was no doubt that this was the most visible manifestation of the G20 crisis.

Russian participation in the summit was cited as the cause of the conflict that prevented general group photography.

Politicising the work of the G20 is detrimental to this format of international cooperation. Additionally, it undermines the stability of the global economic system. Numerous platforms in the world can be used for political demonstrations. Let's take at least the UN General Assembly. It is clear, however, that there is a shortage of institutions for adopting and implementing international economic decisions.

So, it becomes increasingly likely that the world economy will fragment massively during the next global financial crisis.

From seven to twenty

The G20 was established in 1999 in response to the Asian financial crisis in order to coordinate international efforts to stabilise the global economy. The G7 and the IMF alone were not sufficient, even then.

The G20, however, fell into the shadow of the "parent" G7 after the end of the crisis and remained there until the next global financial crisis in 2008. The scale of the financial and economic crisis of 2008 required a fundamentally different level of coordination.

G7's weight in the global economy was already dramatically insufficient, and the G20 became the primary international economic body following the two summits in 2008 and 2009.

Additionally, the G7 was sidelined as an economic format. This was especially apparent in 2014 after Russia's intermediate form (G8) of participation in the G7 was eliminated. The G20 became the centre of gravity for economic decision-making.

The fact that momentary political intrigues destabilise the work of such a pivotal institution today is scary. After all, the global economy and particularly the financial system of developed countries are in such a precarious state that the next global financial crisis can occur literally every day. One medium-sized unpredictable event can trigger a chain reaction of defaults and stock market crashes. And there will be no proper international communication to discuss anti-crisis measures.

From twenty to two

How is the emerging G20 crisis affecting the world? Increasing importance of bilateral relations between the United States and China.

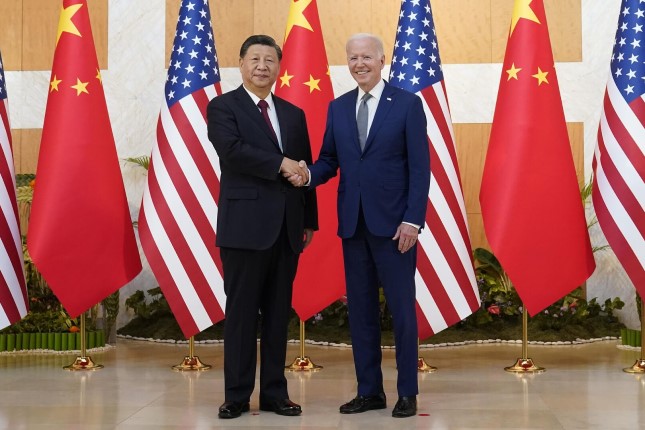

The meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden lasted three hours and twelve minutes. It's quite a lot for this type of meeting. Many observers believe that Biden and Xi's meeting has overshadowed the G20 summit in general because of this.

There is, of course, some truth to this, but only to a certain extent. The Biden-Xi meeting merely highlighted the existence of two poles within the G20, namely pro-American and pro-Chinese. Even though this is not a strict division, it is clear that the G20 is becoming less "multipolar" in comparison with previous summits.

There are three obvious reasons for this. Russia and Europe suffered a breach as a result of the war in Ukraine. Thus, the influence and room for maneuver of both players were immediately restricted. This is the first reason.

Second. The re-election of Xi Jinping for a third term and the results of the elections to the US Congress, which were quite favourable for Joe Biden, stabilised power in both China and the United States. This has become particularly evident in the ongoing instability in Europe and the Middle East.

Third. For a long time, China regarded Europe, with its strong left-liberal forces, as the most convenient partner in globalisation. An example is Xi's high-profile speech at the Davos forum in 2017 when the Chinese leader said that China was ready to struggle to save globalisation (from the American right).

Europe then looked like a welcome partner in this "rescue project". Today, it is a big question.

It has lost its role as a driving force behind liberal globalisation, which explains the special importance of US-China relations. The European Union is no longer a subject of globalisation. This is true both ideologically and economically. The acute energy crisis has sparked the deindustrialisation of the Old World.

The transfer of industrial enterprises and the movement of personnel from the EU to the US and China have already begun. In the chemical industry, BASF, a global leader, aims to reduce production at its primary plants in Ludwigshafen (Germany) and Antwerp (Belgium) while simultaneously building a mega factory in China. This is due to the fact that increased gas prices have made chemical production in Europe unprofitable. Or according to the German newspaper Handelsblatt, more than 60 companies from Germany will move to Oklahoma alone.

What's next?

It is now clear that Brexit was the prologue to the decline of the European model of globalisation. Britain has ceased to see a future for itself within the framework of the European integration project. Moreover, it has chosen to scuttle this project, which is clearly visible during the current Ukrainian conflict.

At the same time, Britain was one of the main actors and beneficiaries of that model of globalisation. Therefore, Brexit looked strange from the outside: the financial centre of globalisation staked on the collapse of this very globalisation. Today the logic of those decisions has become more transparent.

It is clear that the model of globalisation driven by the North Atlantic community cannot be revived. What will replace it?

Three main scenarios

The first is a bipolar world. The United States and China divide the world into two zones of influence, and each of the two centres implements its own model of economic and, in some cases, political integration in its zone. The scenario is good because it will provide maximum control of the deglobalisation process − a minimum chance of major conflicts that could trigger a global military catastrophe. And the long conversation at the G20 summit between President Biden and President Xi about "red lines" suggests this scenario is very realistic.

The second is macro-regions. If the acute phase of the global financial crisis begins before the United States and China can start to cope with it, it will be necessary to return to the multilateral dialogue on anti-crisis measures. In this scenario, it will be necessary to restart the G20 format, in which players of the second and third levels have a high degree of autonomy in decision-making. If it works out, then we can discuss the scenario's implementation for forming the world of macroregions (multipolarity). Especially if, by that time, it will be possible to localise the Ukrainian crisis.

The third is defragmentation. A new global crisis will begin before the United States and China have time to build management schemes in their potential zones of influence (bipolarity scenario).

At the same time, it will not be possible to restart the G20 format (macro-regions scenario), especially with the ongoing hot phase of the Ukrainian crisis and the confrontation between Russia and NATO. Without global economic crisis management mechanisms, the crisis will deepen rapidly.

Multilateral mechanisms for coordinating interests will not work, and the emerging bipolarity (managed competition between two centres of power) will fall into a scenario of forced confrontation, with several phases of increasing escalation. This will lead to the collapse of existing global industrial and logistics chains, the failure of a unified economic system, and growing chaos.