Since Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered a limited mobilisation on September 21 as part of Russia's special military operation in Ukraine, an estimated 260,000 people have fled Russia.

About 100,000 people have crossed into Georgia alone. The number of Russians leaving for Georgia is vast: it is a relatively inexpensive country; the land border is easy to reach, and no entry visas are required for Russians. Armenia has similar advantages as a destination, but it is only accessible by air. As a result, all plane tickets to Armenia sold out as soon as the mobilisation was announced.

It is estimated that another 100,000 people have crossed into Kazakhstan. Thousands of Russians also left for Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Finland recently closed its borders to Russian travellers with tourist visas, while Norway warned that it could also introduce similar restrictions. Both countries require a Schengen visa; besides, even a short stay is associated with considerable expenses.

There is only one border crossing between Russia and Georgia. It is the Upper Lars checkpoint that straddles the only road running through the Daryal Gorge. On the day of the mobilisation announcement, it took only a few hours to cross the border here. Two or three days later, the mountain pass turned into an apocalyptic scene, with thousands of people packing this narrow gorge. A week later, a full-scale humanitarian disaster broke out as nearly 6,000 cars got stuck in an endless traffic jam. Thousands of people, some with small children, headed for the border on foot. Since no one expected the crossing to drag on for several days, people quickly ran out of water, food and gasoline. In the early days of the crisis, some locals offered to sell scarce supplies at exorbitant prices. There were practically no toilet facilities along the route, so travellers had no choice but to do their business outdoors by the Terek River.

Things were slightly more civilised on the border between Russia and Kazakhstan. Firstly, there are more border crossings into Kazakhstan. Secondly, most of them are located in the Asian part of Russia and Siberia, where the flow of people is considerably lower.

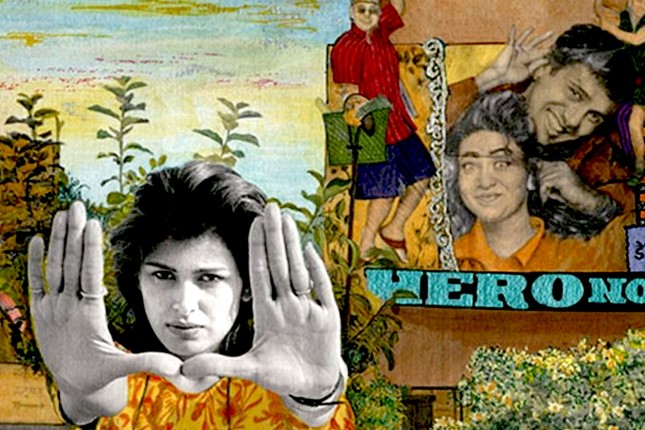

A cold reception for Russian fugitives in Georgia.

These people are fleeing to escape the draft. It would be an exaggeration to say that all of them are against the war. To be precise, most are firmly against their involvement. Belonging to the so-called "creative class", many of them have been "above politics" for so long that even now, they do not seem to realise what implications their decision to flee is likely to have both for themselves and their loved ones.

Housing prices have soared in Tbilisi lately, but accommodation in the capital is still hard to find as many people do not want to live in the provinces. The housing market is similar in Central Asian republics.

Since rental payments increased, many landlords have been kicking local tenants out to rent the same apartments to Russians at a higher price. Before long, some Russians will realise that working remotely is not an option. Competing for jobs with locals is an exercise in futility. The influx of foreigners can easily stoke tensions, resulting in ethnic conflicts and violence.

Simmering conflicts are beginning to boil over again. Georgia has renewed accusations that Russia annexed Abkhazia and South Ossetia, two national republics that Tbilisi considers an integral part of its country.

In August 2008, Georgia unleashed a war against South Ossetia, an act of aggression later confirmed by an EU commission headed by Swiss diplomat Heidi Tagliavini. When the conflict broke out, Russia's armed forces helped South Ossetia to repel the attack and defeat the aggressor. A few weeks later, Moscow formally recognised Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states.

The consensus in Georgia is that Russia is to blame for the loss of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. If fact, this view is shared not only by nationalists but by Georgians from all walks of life.

"Don't you dare call yourselves refugees," local activists are saying to fleeing Russians, adding that genuine refugees were those who fled Tskhinvali and Sukhumi to escape the advancing Russian army. Young Georgians are demanding that the authorities should close the Upper Lars border crossing. "Russians, go home. You are not welcome in Georgia!" anti-Russian demonstrators are chanting as they parade through the streets of Tbilisi.

Georgians have every reason to believe that the influx of Russians will pose political, social, and economic risks to Georgia.

"At this rate, Russians will make up 10% of Georgia's population in a matter of days," say those who are opposed to the idea of accepting large numbers of Russians.

"This will be a grave threat to Georgia's national interests because Russia may take advantage of this opportunity to launch an aggression against Georgia."

A long line of cars at the Russia-Kazakhstan border.

Most of those who have crossed into Georgia feel lost. The same is true of newly arrived Russians in Central Asian republics, countries with radically different lifestyles. Russian hipsters do not seem to realise what kind of society they are in now or what they will do next. Nor do they know at this point how they will make money or where they will live.

These people have never been interested in history, so they have a hard time understanding why the Georgians or many Kazakhs don't want to welcome them.

This is just the beginning as thousands of people, utterly unadapted to reality, continue to head for the borders. What is going to happen to them abroad? How will they be able to arrange their lives? What if they come to regret their decision to flee?

The Russians who fled to escape the mobilisation are actually at a dead end: most of them simply have nowhere to go from Georgia and Central Asian republics. Amid fears that Russians could pose a security threat to EU countries, the European Commission has recommended that EU member states should make "stricter assessments" of visa applications made by Russians from third countries.

"The fact that you do not want to go to Ukraine and fight there does not mean you are not a threat to the European Union," said European Commissioner for Home Affairs Ylva Johansson. However, she said all Russians still had the right to apply for asylum in the EU, which may be granted to those fleeing the war on a case-by-case basis.

Generally speaking, those who remain in Russia have no sympathy for those who have left. "They don't know what they are getting themselves into!" the old-timers are saying about the fugitives with some malicious joy. "No one likes traitors," "You brought it upon yourselves," and "You are going to have a rough time there" – these are just some of the most recent comments posted on social media and messaging apps in reference to the flight of people from Russia.

Many posts also include the following questions: "Just imagine how you will be treated when you come back? How are you going to look your friends in the eye?"

Some comments end with the following grim observation: "At a time like this, it's better to be among your own people with a gun than to be unarmed among strangers."

In 1939, the US shipped Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany back to Europe.

"There's no point in fleeing – you can't fight fate," many people have summarised lately. On the one hand, the summary is a typical manifestation of the Russian national character, which is state-oriented and fatalistic at the same time. On the other hand, this conclusion reflects the realities that Russians "on the run" will now have to face.

Similar events have occurred both in Russian and European history. For instance, Russians who emigrated after the 1917 Bolshevik revolution were destined to roam worldwide. First, from Constantinople (Istanbul) to Prague. Then, from Prague to Paris. Lastly, from Paris to the United States or Latin America. Most of the émigrés spent their entire life moving from one place to another but still failed to put down new roots, let alone feel at home in a foreign land.

The same fate befell other political refugees who fled Spain under Franco, Nazi Germany and the United States during McCarthy's witch hunts. Just some of them were lucky enough to settle down successfully abroad. Their new life usually paled with few exceptions compared to what they lost at home.

To a large extent, the fate of refugees had little to do with their efforts, as they were primarily at the mercy of political and even geopolitical factors in the countries they fled to and the world as a whole.

A refugee's lot is perhaps the last thing anyone could wish for. However, some choose to leave. For others, it is easier to remain at home no matter what. They say you can't fight fate, but you can certainly try to change it. Eventually, regardless of where a person resides, they will inevitably be bound by the nation's fate.

Main photo: Border crossing between Russia and Georgia.