Germany has seen a surge in the number of cases where children have been taken away from their Ukrainian refugee families by the country's juvenile justice services. According to testimonies brought forward by the mothers who have been affected by this, local services take their children away from them for no apparent reason, often at the request of third parties, and then move to suspend these refugees' parental rights and even strip them of those rights altogether later by placing a child with a local foster family or in an orphanage. These interventions by child custody services are usually instigated by the refugees' neighbours, doctors, or families that had been hosting Ukrainian refugees. Social networks and Ukrainian media have already reported over 100 such cases.

Moreover, not a single family has yet succeeded in securing a return of their illegally abducted child. Attempts to petition the Ukrainian embassy have also proved to be futile. The Embassy's representatives keep referring to Germany's law that stipulates that anyone who gets registered as a refugee in Germany is entitled to "prompt temporary protection," "the right to social benefits", as well as social welfare payments, coverage of their medical care expenses, and adequate housing, and therefore becomes subject to the sole jurisdiction of the German law. In other words, the unfortunate parents are essentially being reminded that they have already been paid through the German welfare system and that they will have to sort out their problems on their own.

Ukraine's online media outlet Strana.ua published testimonies provided by Ukrainian women who had had their parental rights restricted by Germany's juvenile justice authorities. According to their testimonies, juvenile justice officials take their children away based on complaints and requests filed by German citizens (including families that had provided shelter to these refugees, neighbours, doctors, psychologists, etc.).

Following lightning-fast court proceeding that are rarely understood by the Ukrainians due to their lack of knowledge of the local language and their lack of means to use the costly services of German lawyers, the refugees' parental rights are often suspended or restricted indefinitely. Their children are placed in orphanages or with foster families, and their parents are often forbidden to see them for more than a few hours a month. The affected Ukrainians are deeply concerned that they might be stripped of their parental rights altogether and that their sons and daughters will be taken away from them forever and put up for adoption by German families.

According to one of the affected Ukrainians, Elena from Dnipro (formerly, Dnipropetrovsk), as quoted by the authors of the article published on Strana.ua, her four-year-old son was taken away straight from the sandbox where he had been playing, without even bothering to provide any evidence that this removal was indeed necessary or legally warranted. Elena claims that the German couple she was staying with "had written a complaint alleging that she was not looking after her child properly, was not feeding him well, and was overly emotional about her daily discomforts."

And yet, it is plain to see for any rational individual that all of these accusations are nothing more than one's subjective assessment of a given situation. Who is to define what it means to "not feed someone well"? After all, all children have different dietary habits. And to another witness, an "overly emotional" mother might not seem emotional enough and cause them to suspect that the mother is in fact insensitive and indifferent.

Another Ukrainian refugee, Oksana Buratevich from Kyiv, claims that it was the German doctor who had been treating her child who filed a complaint against her with the juvenile justice authorities. "He claimed that I was overly concerned about my child's medical care, which allegedly triggered my son's psychosomatic diseases," the refugee told reporters. "They broke into my apartment at 10 p.m. by kicking the door in and announced that they were going to take my child away from me based on that doctor's insinuations."

It is a well-known fact that German law seeks to protect children's interests and interprets the notion of "cruel treatment" as broadly as possible. In any case, this is something that people who had come to live here from the former Soviet Union often write about on social media. According to them, what would be considered a norm in Russia or Ukraine − such as hearing sounds of shouting or screaming coming from a neighbour's apartment or seeing someone give a light slap on their child's behind − could result in the child's removal from his or her parents' custody in Germany.

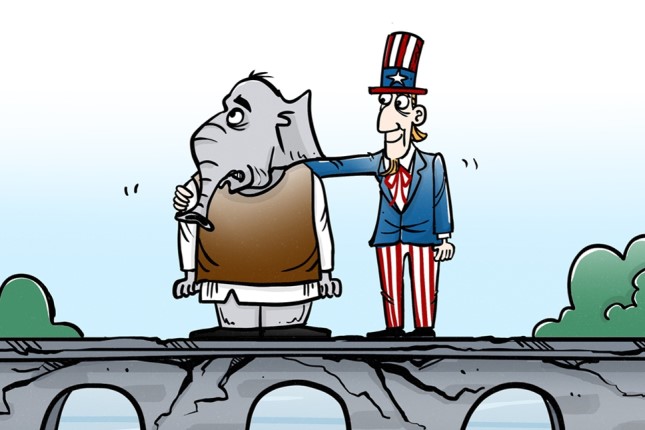

Ukraine's diplomats try not to interfere with the actions of the German juvenile justice officials, arguing that everyone who has been granted refugee status in Germany becomes subject to Germany's jurisdiction. However, such a position is not without a modicum of fallacy. It is indeed a fact of law that all foreigners in their host country must abide by the laws of the host country.

But this fact cannot by any means be construed to serve as a basis for depriving foreign nationals of their right to diplomatic protection by the authorities of their home country. This is all the more true in the case of children as their country's most vulnerable citizens who do not yet have their own legal capacity, status, resources, or experience to defend their rights.

Elena from Dnipro (Dnipropetrovsk) explained to Strana.ua what happened to her child after he was taken from his mother. "At first, they took my son to an orphanage, and ten days later he was handed over to an unknown family. The first court hearing was not held until two weeks later, and at that hearing I was told that I would be able to see my son only once every eight months."

What we have here is a situation where a preschool-age child, who is a citizen of Ukraine, a Slav speaking no German, was taken from his birth mother without any explanation and turned over to a German family that is completely foreign to him to provide him with temporary (?) care.

The boy's contacts with his mother have been curtailed to such an extent that this could effectively be construed to amount to a complete prohibition on any such contracts. The child is only four: and at that age, in the space of eight months, he can simply forget his native language and start assuming that he is German, especially if his foster family makes a strong enough effort to make this happen.

All this is oddly reminiscent of the case of the "Lebensborn" project in Nazi Germany. Soon after World War II broke out, the Germans started snatching away Slavic children (mostly from Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Poland) whose parents looked "Aryan" and placing them with German families where they were "re-educated" to quickly forget their origins.

Today's situation may turn out to be very similar to that in many respects. What is currently being used as the grounds for removal (which is also true in the case of many Scandinavian countries where this practice is also fairly common) includes not only the so-called social conditions, "illnesses caused by parents", or " the mother's overly emotional responses," but also things like the children's Slavic parents' views on LGBT rights or on gender reassignment.

There are both purely social reasons for such policies to exist (including vulnerability of female refugees who find themselves in a culturally alien environment without the support of their men) and demographic reasons as well. Germany has been afflicted by a low birth rate, at about 1.6 children per woman, and that number is mostly contributed to by immigrants from Asian countries.

There may, therefore, be a great temptation to "strengthen up" the country's titular population by Germanizing the "Ostkinder" taken away from their defenseless Ukrainian mothers (there are currently over 1 million registered refugees from Ukraine living in Germany, most of whom are women and children), especially considering that there has clearly been a precedent like that in the country's not-so-distant history.