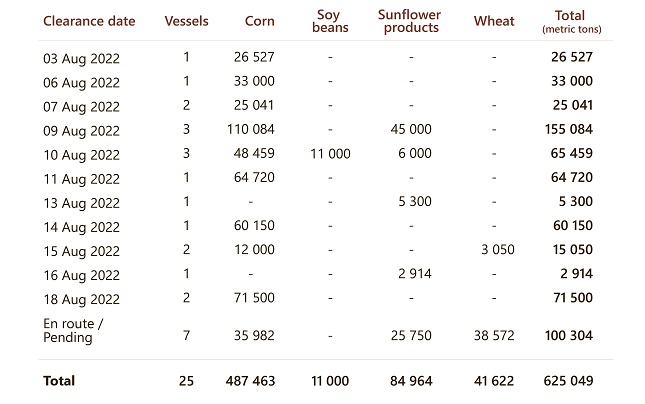

Ships leaving Ukrainian ports with grain as part of the Istanbul agreements of July 22 are heading to Western countries instead of starving African states, as follows from the UN Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre data. The data also show that the cargo consists mainly of corn and sunflower oil rather than wheat, which, western politicians say, is in short supply to Africa and the Middle East. All this puts a question mark over the actual dependence of global food security on the grain deal to unblock Ukrainian ports.

Reuters quoted the Turkish Defence Ministry as saying that two more ships carrying grain left Ukraine's Black Sea ports on Saturday, August 13, 2022, bringing the total number of vessels departing the country under the UN-brokered deal to 16. Meanwhile, the UN World Food and Agriculture Organisation managed to charter only one bulk carrier directly to the countries suffering the most from food shortages.

According to The New York Times, most ships loaded with Ukrainian grain are heading for developed countries eager to pay more and in a lump sum, such as the UK, Ireland, Italy, China, South Korea, and Turkey. Meanwhile, the European markets have seen a substantial increase in crop demand due to poorer harvests caused by the severe drought and the shortage of mineral fertilisers from Russia and Belorussia. UN spokesman Stephane Dujarric admitted earlier that the deal had run up against "commercial interests". Although as recently as a month ago, when the UN negotiated the grain deal with Ukraine, Russia and Turkey, officials had high hopes that it would unlock millions of tonnes of foodstuffs for African countries on the verge of starvation.

Bulk carrier Polarnet leaves the seaport in Chernomorsk. Photo: Reuters.

The Politico reported that according to a document from a hacked UN email, a special task force set up to address food insecurity had expressed concerns that poorer countries would not be able to buy Ukrainian supplies due to competition with richer states. This concern was also voiced at one of the meetings attended by UN Secretary-General António Guterres. According to the correspondence seen by the journalists, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation's Josef Schmidhuber asked whether the Black Sea deal included any provisions guaranteeing that poorer countries would be able to afford to buy the newly freed Ukrainian grain. He received no answer.

The cynicism is that local companies in famine-stricken countries, too, pursue their profits, disregarding the interests of their populace. A vivid example is the Sierra Leone-flagged cargo ship Razoni, the first to leave the Ukrainian port of Odesa with 26,527 tonnes of corn. Ship was supposed to go to Lebanon, which was in dire need of food, but after a corn buyer refused to take delivery because it was five months late, Razoni docked in Mersin, Turkey. When the ship put to sea again, its transponder was off. According to MarineTraffic, the ship was last sighted on August 12 between Cyprus and Syria.

Bulk carrier Razoni passes the Bosphorus. Photo: newsru.cgtn.com

Some experts have previously warned that Ukrainian wheat, corn, and other crops are unlikely to reach the Global South. The whole project with a safe corridor from Ukraine was initially conceived so that rich countries could stock up on food at a discount. And they do succeed in it, as Kyiv offers wheat 20 dollars per tonne cheaper than Russia. In addition, Turkey benefited from the deal. Earlier, The Columnist wrote that the agreements signed in Istanbul make Turkey the main centre that will distribute Ukrainian grain to the Middle Eastern countries. In this regard, some journalists have already dubbed Erdogan the sultan of grain.

The UN repeatedly cited the blockade of Ukrainian ports as the main reason for the hunger crisis in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. Experts of the global organisation said that 323 million people are threatened with hunger because of the situation in Ukraine. Nevertheless, now that the ports are unblocked, and the grain is exported, these hundreds of millions of people are still facing the threat of starvation. The New York Times wrote that energy prices remain high, which impacts the cost of operating farm equipment and transporting wheat to market and affects the cost of fertiliser. At the same time, hot and dry weather, which reduces yields, is becoming more common. The New York Times quoted analyst Ehsan Khoman of Japanese bank Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group: "The fundamental picture has not really changed. There is a potential where food prices could spiral out of control."

Grain distribution among the hungry in Ethiopia. Photo: independent.co.uk

According to analysts from The International Crisis Group, it is not a deal on food exports from Ukrainian ports that will cut food prices. Emerging economies can only rely on the impending recession that will reduce demand and lower food prices. But this, of course, is also a bleak prospect.

Main photo: Children queuing for food. South Sudan © loreeunleashed.com