To grasp why so many Scots voted to leave the United Kingdom 10 years ago today in a referendum on Scottish independence — held Sept. 18, 2014 — we need to understand the history of a union that was born in mercantilism and sustained by centuries of empire and colonialism.

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland — to give the U.K. its Sunday name — is the very epitome of an artificial state. It was and remains the product of the grafting together of divergent cultures, histories and national identities.

At inception, this grafting together was undertaken not in the interests of its peoples but in the interests of national elites eager to take advantage of the commercial opportunities of a unified polity with added manpower and resources. This in an age of empire.

The venality, greed and corruption of the Scottish ruling class in the early 18th century delivered the Scottish people into the arms of what at the time was an unpopular union with its neighbor south of the border. This was reflected in the social unrest and riots that ensued in Scottish towns and cities both during the negotiations that brought into being the 1707 Act of Union, and upon its passage.

For the ruling elites of both Scotland and England the union of both parliaments into one had demonstrable commercial and strategic benefits. The former had been left bankrupt after Scotland’s failed attempt at establishing its own overseas colony in Darien (modern day Panama) in the late 17th century.

In order to forestall national immiseration the need to gain trading access to England’s overseas colonies was now considered essential.

Over time a working class identity was forged across the U.K. as a product of the country’s heavy industries – coal mining, steel, shipbuilding, etc. — via the U.K.’s Industrial Revolution. Common economic interests and struggles against a common enemy, the bosses and owners of those industries, transcended national and cultural differences.

It led, ultimately, to the birth of the country’s trade union movement and the formation of the Labour Party at the start of the 20th century.

Margaret Thatcher destroyed this material basis of working class unity across the U.K. in the 1980s. Her free market, neoliberal counter-revolution and resulting deindustrialization of the nation’s economy turned Britain into what it is today: a service economy underpinned by financialized capital.

Thatcher and everything she stood for was particularly reviled in Scotland.

Her economic shock therapy destroyed communities across the country, rendering them bereft of a future. The result was politics being viewed in Scotland through a national rather than class lens, leading to growing support for separation.

A Major "Yes"

Ten years ago 45 percent of Scots who cast a vote in the independence referendum did so in favour of separation from the rest of the U.K. Considering that such a vote constituted an almighty leap of faith after 307 years of union, this was an incredibly large Yes to independence vote.

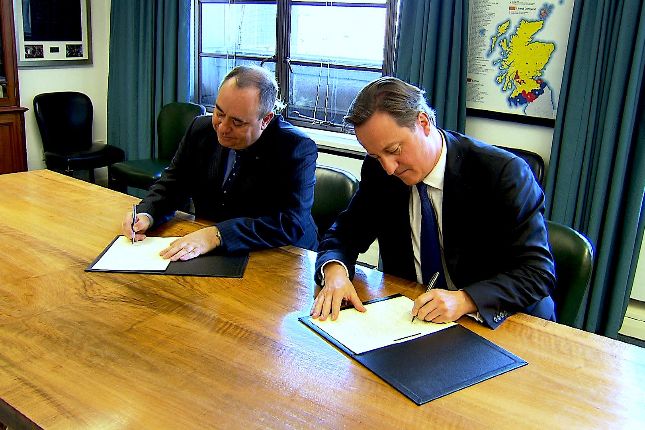

First Minister of Scotland Alex Salmond and U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron sign the Edinburgh Agreement paving the way for a referendum on Scottish independence, Oct. 14, 2012. Photo: The Scottish Government, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0.

When then British Prime Minister David Cameron agreed to the referendum, he did so with the hubris of a scion of English privately-schooled exceptionalism. He believed there was no chance of people in Scotland voting to separate from the U.K.

It is hard to imagine, with this in mind, that British rulers would ever risk giving people in Scotland the opportunity to vote on independence again.

The stakes involved could not be higher for guardians of the U.K. establishment — what with the threat to the future of the U.K.’s Trident nuclear submarine base in the West of Scotland by which London has been able to present itself as a major power on the global stage, and by which it occupies its seat as a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council.

Submarine HMS Victorious, armed with the Trident missile system, returning to home port at HMNB Clyde, Faslane, Scotland, April 2013. Photo: Defence Imagery, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0.

There has long been an uneasy relationship to nationalism among socialists and those who sit on the left of the political spectrum in Scotland. When harnessed in the cause of national liberation, it is a positive force, but when harnessed in service to national chauvinism, it is not.

“Nationalism,” said famed Scottish trade union leader and organizer, Jimmy Reid, “is like electricity. It can keep a baby alive in an incubator or it can kill a man in the electric chair.”

English/British nationalism, responsible for Brexit, is of a different order and a different animal from its Scottish variant. In the Scottish independence referendum of 2014, EU nationals then living, working and loving in Scotland were afforded a vote. They were denied the same privilege two years later in the Brexit referendum, which in large part was a referendum on their fate and future in the U.K.

It is in this context that Jimmy Reid’s above formulation should be understood.

Yes, true, deindustrialization did not only ravage Scottish working class communities. It also ravaged working-class communities across England. The difference is that Scottishness is an identity largely forged before the Union of 1707.

It is rooted in the Wars of Independence against the English waged by William Wallace and Robert the Bruce in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. It is rooted in the ill-fated Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. And on a cultural level it is rooted in the works of Robert Burns, popularly known as “Scotland’s Bard” (national poet).

Scotland is a European nation — in the geopolitical sense — to the extent that England is not. Brexit was, in this writer’s opinion, driven by an emotional reach back in time to a supposed golden age, when Britannia ruled the waves and the Union Jack flew wherever it damn well pleased.

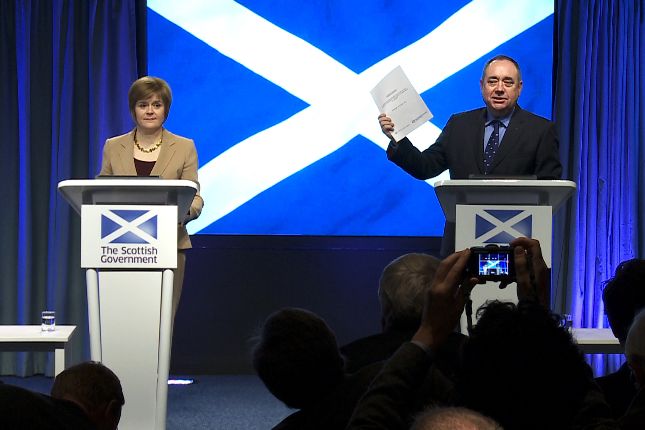

The national campaign for Scottish independence in 2014 was underpinned by inclusivity not its antonym. If there was any sense of exceptionalism involved it was exceptional pride in being inclusive and welcoming to migrants and ties with our European neighbors. It was a campaign that was led by then first minister of Scotland and leader of the Scottish National Party (SNP), Alex Salmond.

Nicola Sturgeon and Salmond at a press conference following the signing of the Edinburgh Agreement, Oct. 15, 2012. Photo: Scottish Government, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0.

Salmond, a former banker, was never more popular than he was in those days. He was like a vessel into which countless Scots poured their hopes and aspirations for a break from a reactionary British Tory establishment.

In what has to count as a Shakespearean denouement to this tumultuous period in Scottish affairs, Salmond resigned as head of the SNP and as first minister of Scotland immediately after the referendum was lost.

His deputy and close colleague, Nicola Sturgeon, took his place. A few years later she helped to engineer the criminal case that was brought against him surrounding allegations of sexual abuse, up to an including attempted rape.

In March 2020 a jury found Salmond not guilty on all charges. He walked out of court a free, but greatly diminished man and political figure.

As for Sturgeon, at this writing she is the subject of a police investigation into embezzlement and fundraising fraud. The SNP, for years an electoral powerhouse in Scotland, is now in free fall. It shows no sign of recovering anytime soon.

What was in touching distance a decade ago in the form of an independent Scotland, free from London rule, increasingly appears an idea whose time had come but is now, sadly, gone.

Future generations may live to regret that it has.

Main photo: A Scottish independence rally in 2018 © Azerifactory, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Source: Consortium News.