U.S. President Joe Biden declared in a televised address on Oct. 25 that, when it came to relations between Palestine and Israel, “There’s no going back to the status quo as it stood on October 6,” the day before Hamas launched its surprise attack on Israel, triggering Israel’s ongoing attack on Gaza.

Biden’s words echoed those of his secretary of state, Antony Blinken, who the day before told the United Nations Security Council there could be no peace in the Middle East without the Palestinian people “realizing their legitimate right to self-determination and a state of their own.”

Blinken followed up this pronouncement on Nov. 3, declaring in a press conference that the U.S. was committed to a two-state solution for Israeli and Palestinian states. “The best viable path, indeed the only path, is through a two-state solution,” Blinken said. “The only way to end the cycle of violence once and for all.”

This White House has been expressing support for a two-state solution ever since Biden took office. Blinken had a hard time getting traction on this policy, however, while Israel struggled with forming a government after an extended period of political deadlock that witnessed four inconclusive elections (April 2019, September 2019, March 2020 and March 2021) in three years.

In November 2022 the Israelis went to the polls for a fifth time, and this time the veteran former-prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, was able to secure enough votes and political support to assemble a far-right governing coalition.

Israeli President Herzog assigning task of forming a new government to Netanyahu, Nov. 13, 2022. Photo: Kobi Gideon / Government Press Office / CC BY-SA 3.0 / Wikimedia Commons.

While Netanyahu’s victory ended Israel’s electoral nightmare, it also proved to be the death knell for the Biden administration’s aspirations for a Palestinian-Israeli peace process premised on a two-state solution.

The governing coalition Netanyahu had cobbled together was more inclined toward the eradication of the existing Palestinian Authority than resurrecting a vision which, from the perspective of Israel’s radical right, had died with Yitzhak Rabin on Nov. 4, 1995.

For the Biden administration to speak of pushing a two-state solution in any post-conflict negotiation would require that Netanyahu jettison his governing coalition, an act that would be terminal to his political future. This is widely known within the U.S. government.

Post-Conflict Israel

As such, for Biden and Blinken to posture in favor of a two-state solution so aggressively, it must be done with the working assumption that a post-conflict Israel will be governed by a political leader capable of supporting an idea which had been extinguished, in so far as Israeli politics is concerned, nearly three decades ago.

Even if such a governing coalition could be crafted together to politically sustain the idea of a two-state solution that fails to resonate with Israelis and Palestinians alike, there remains the ultimate hurdle that needs to be cleared before any notion of a lasting peace between Israeli and Palestinian states premised on the notion of equality — Israel’s nuclear weapons program.

Israel’s representative addressing meeting on the NPT Safeguards Agreement with Iran at the International Atomic Energy Agency headquarters in Vienna, March 4, 2021. Photo: Dean Calma / IAEA / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0.

The question of Israeli nuclear weapons has befuddled every American president since John F. Kennedy. The issue came to a head in 1968, after the U.S. signed the nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT). The treaty was signed by President Lyndon Johnson on July 1, 1968. Issues of implementation, however, fell to his successor, Richard Nixon.

One of the major policy issues facing the Nixon administration was the status of Israel’s nuclear weapons program. The Nixon administration was firmly committed to the NPT, and as such was obligated to adhere to U.S. laws prohibiting the sale of military technology to a nation operating in violation of the NPT or, as in the case of Israel, possessed nuclear weapons capability outside of the framework of the NPT.

Nixon was advised by his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, to pressure Israel into signing the NPT and being disarmed of its nuclear arsenal. Nixon, however, balked at the notion of being seen as pressuring Israel on an issue of national security, and instead opted to embark on a policy of nuclear ambiguity, where Israel promised not to be the first nation to “introduce” nuclear weapons to the Middle East, so long as it was understood that “introduce” did not equate to “possession.”

US Diplomatic Cover

Blinken boarding plane in Israel heading to Jordan, Nov. 3. Photo: State Department / Chuck Kennedy.

Some five and a half decades later, the United States continues to provide diplomatic cover for Israel’s nuclear weapons, maintaining the fiction of ambiguity despite knowing full well Israel possesses a very robust nuclear arsenal. This posture is becoming more difficult to sustain, given the increasingly aggressive posture assumed by the Israeli government regarding its own policy of ambiguity.

In 2022, during a periodic review by the United Nations of the NPT, then-Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid addressed the Israeli Atomic Energy Commission about Israel’s “defensive and offensive capabilities, and what is referred to in the foreign media as other capabilities. These other capabilities,” Lapid said, clearly alluding to Israel’s nuclear weapons, “keep us alive and will keep us alive as long as we and our children are here.”

As things stand, the threat posed by Israeli nuclear weapons to both regional and global security is as great today as at any time in Israeli history. With the potential of the current Palestinian-Israeli conflict expanding to include Hezbollah and perhaps Iran, Israel for the first time since 1973 faces a genuine existential threat — the kind of threat Israel’s nuclear weapons were built to deter.

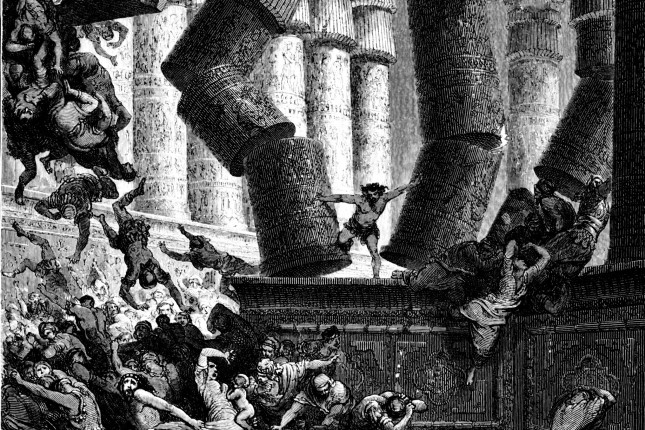

An Israeli minister has already alluded to the attractiveness of using nuclear weapons against Hamas in Gaza. But the real threat comes from what happens if Iran is dragged into the war. Here, Israel’s much rumored “Samson Option” could come into play, where Israel uses its nuclear arsenal to destroy as many enemies as possible once the continued survival of Israel is at risk.

The Death of Samson, 1866, by Gustave Doré. Photo: English Bible / Public domain.

Given the present risk posed by Israel’s nuclear arsenal, it is essential that the current Palestinian-Israeli conflict be prevented from expanding. Once the conflict can be ended, the process must begin for a long-term solution that includes a free and independent Palestine. However, a new Palestinian state can never be free if its neighbor, Israel possesses nuclear weapons.

Operating with the understanding that the creation of a Palestinian state would coincide with a renewed push for normalization of relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors, the result vis-à-vis the security of Israel would be a much-improved situation that made Israel’s need for nuclear weapons moot.

South African Example

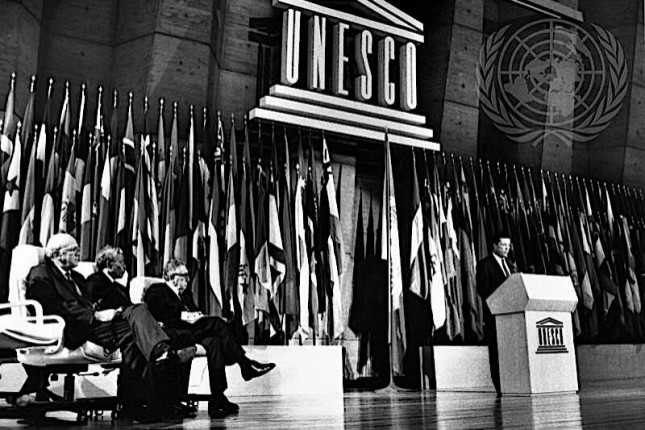

UNESCO Peace Prize award ceremony in Paris on Feb. 3, 1992. Seated from left are the two recipients — South African President de Klerk and African National Congress President Nelson Mandela — and Henry Kissinger, a former U.S. secretary of state and chairman of the selection jury. Photo: UN Photo / JP Somme.

The question then becomes how Israel can be persuaded to voluntarily give up its nuclear weapons. Fortunately, there is an example from history.

Apartheid South Africa had embarked on a nuclear weapons program in the early 1970s. U.S. intelligence reports show that South Africa formally began its nuclear weapons program in 1973. By 1982, it had developed and built its first nuclear explosive device.

Seven years later, in 1989, South Africa had manufactured six functional nuclear bombs, each capable of delivering an explosive equivalent of 19 kilotons of TNT.

The South African nuclear weapons program mirrored that of the Israeli program in that it was conducted in great secrecy and designed to deter the threat posed by communist-supported black liberation movements operating all along the periphery of the South African nation.

In 1989, South Africa elected a new president, F. W. de Klerk, who quickly realized that the political winds were changing and that the country could very well, in the span of a few years, fall under the control of black nationalists led by Nelson Mandela.

To prevent that, De Klerk took the unprecedented decision to join the NPT as a non-nuclear state and open its nuclear program for inspection and dismantlement. South Africa joined the NPT in 1991; by 1994, all South Africa’s nuclear weapons had been dismantled under international supervision.

Once the Palestinian-Israeli war comes to an end, and if Israel begins negotiating in good faith about the possibility of a free and independent Palestinian state, the United States should lead an effort to get the Israeli government to follow the path taken by F. W. de Klerk by signing the NPT and working with the International Atomic Energy Agency to dismantle the totality of Israel’s nuclear arsenal.

Such a move should be non-negotiable — if the United States is serious about creating the conditions of a long and lasting peace between Israel and Palestine, then it should use all the leverage at its disposal to pressure Israel to voluntarily disarm itself of nuclear weapons.

This is the only viable path to peace between Israel and the Arab and Muslim world that surrounds it.

Main photo: Palestine solidarity march in London on Oct. 9. Alisdare Hickson / Flickr / CC BY-SA 2.0.

Source: Consortium News.