While the "special military operation" in Ukraine may not be religious per se, it is nevertheless inextricably bound up with religion. It has had serious consequences for the Orthodox Church in Ukraine and throughout the Baltics.

Both the civil and spiritual leaders of Russia have spoken of the spiritual aspect of the ongoing conflict. In his speech on the eve of the start of the conflict last year, President Vladimir Putin spoke of Ukraine as more than just a neighbouring country but as an "inalienable part of our history, culture, and spiritual space."

He also noted that the Ukrainian authorities are actively "preparing the destruction of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate."

And Patriarch Kirill, the head of the large and influential Russian Orthodox Church, has spoken of the conflict many times in his homilies (which are followed closely by the international media), emphasizing the need to maintain the unity of the ancient Holy Rus', which encompasses today's Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus.

The whole world read how on March 6 last year, the Patriarch spoke of the "metaphysical meaning" of the conflict—between traditional values in Russia and the Donbas and those of the Western world, best exemplified by the gay pride parades held annually in Kyiv. "This is about something else and much more important than politics. We are talking about human salvation," he said.

On September 25, he preached that those who die in battle, fulfilling their military duty, offer themselves as a sacrifice for others and therefore receive forgiveness of sins (though it must be said, contrary to many unscrupulous media publications, the Patriarch did not limit this to Russian soldiers, and did not say anything about forgiveness of sins coming from killing Ukrainians). These statements found few sympathetic ears outside Russia, including among his fellow Orthodox bishops in other countries.

And while President Putin's concern for the Ukrainian Orthodox Church is certainly not unfounded, the irony is that the situation for the Church was markedly better under President Zelensky than under his predecessor, Petro Poroshenko, who is an open enemy of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. After he teamed up with the US State Department and the Orthodox Patriarchate in Istanbul (once the most prestigious, it is now driven by envy of the size and influence of the Moscow Church) to create a new "Orthodox" church in 2018, hundreds of churches were violently seized and forced to join this new organization. Not a few priests and laypeople, including old babas, received bruises and much worse.

But then Zelensky easily defeated Poroshenko, attracting many with his hands-off approach to religious matters. While the persecution of the Church did not completely stop, the church seizures largely dried up, and the Church was able to breathe again.

There were legal attempts to ban the Church and seize its holy sites under both presidents, but cooler heads always managed to prevail. However, there are fewer and fewer cool heads since last February, and things are looking much worse for the Church.

The issue is that the Church in Ukraine has been part of the Russian Orthodox Church for the past 300 years. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian Church has enjoyed broad autonomy. It has been administered entirely from Kyiv rather than Moscow, though until recently, it still maintained a canonical connection with the Russian Church.

Thus, although the Ukrainian bishops, including their head bishop, Metropolitan Onuphry of Kyiv, have repeatedly condemned the war, the laity of the Ukrainian Church has spent millions helping their suffering countrymen, including frequent equipment donations to the Ukrainian army, although they even fight and die in the Ukrainian army, many among the authorities and the nationalists insist that they are nothing more than a Russian fifth column (the Poroshenko-created "church," on the other hand, has an identity that consists entirely in being not Russian).

The violent church seizures have significantly ramped up again over the past year. And, to be fair, there are those clergy and laity among the Ukrainian Church who could no longer countenance being part of the overall Russian Church and so voluntarily joined the Poroshenko group.

However, the Ukrainian Church remains by far the largest religious organization in the country, and at a council in late May, the Church as a whole decided to separate itself from the Russian Orthodox Church, feeling that they had been practically abandoned by Patriarch Kirill already anyways. Even before that, many dioceses in Ukraine had stopped praying for the Patriarch as their highest authority.

But too many in Ukraine cannot bring themselves to accept the reality of the Church's stance and insist on seeing their fellow (patriotic) Ukrainians as the enemy. There can be no doubt that the Church situation has significantly deteriorated over the past year (by the way, state pressure on the Church in other former Soviet countries—Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Moldova—has also increased in light of the conflict, but nothing like what is unfolding in Ukraine).

Hundreds of churches and other religious buildings have been destroyed or seriously damaged by shelling, with each side blaming the other. Ironically, most of these churches belong to the Ukrainian Church that the Russian President and Patriarch talk about protecting. Clerics, monastics, and simple laypeople have been caught in the crossfire.

But just as Patriarch Kirill and the Russian Church are responsible for their miscalculation (certainly they weren't counting on the Ukrainian Church breaking away in May), so the Ukrainian state is responsible for responding to the fight with Russia by … persecuting its own people, which has dramatically increased since December.

Over the past few months, the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) and local law enforcement have been busy raiding Church administration buildings, churches and monasteries, and bishops' private residences, searching for any book, photo, document, or item of any kind with any connection to Russia. In its reports, the SBU proudly displays pictures of Russian Church calendars and theological books as evidence that the Ukrainian Church is anti-Ukrainian. There have even been several cases where agents have planted boxes of hastily printed pamphlets with random quotes from Patriarch Kirill stitched together.

In some cases, the searches have led to formal criminal cases against bishops and other clerics. One bishop is currently under house arrest. Others have been personally sanctioned by the state (limiting their financial and travel opportunities), including the Ukrainian Orthodox Church's chancellor and the Kyiv Caves Lavra abbot—the single most important religious site in all of Ukraine.

In Ukraine, the Kyiv Caves Lavra and other most important sites are still state-owned—an inheritance from the Soviet Union. The Church has already been expelled from one-half of the Kyiv monastery in favour of the pretender church created by Poroshenko and friends. Both state and nationalist figureheads openly declare that they will see the Church be entirely expelled from the site in Kyiv and from the Pochaev Lavra in Western Ukraine—the second most important site.

Amazingly, another 18 bishops have been deprived of their Ukrainian passports and citizenship with but the stroke of a pen. And several bills before the Verkhovna Rada—the Ukrainian Parliament—aimed to completely dissolve the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, which is the spiritual home of millions upon millions of Ukrainians. While such designs have failed in previous years, deputies are surer than ever that the bills will pass this time around.

At the same time, despite the massive state pressure on the Church, some analysts believe that Ukraine will not go so far as to outright ban the Church because this would be too strong of a talking point for Russia.

A top Russian hierarchy recently raised the issue of Church persecution in Ukraine with the UN Security Council. Still, the Ukrainian Church, which completely rejects Patriarch Kirill's stance on the conflict, rejected the gesture, emphasizing that it separated from the Russian Church months ago and never asked for nor authorized the Russian Church to represent it on the international stage. The head of the Ukrainian Church, Metropolitan Onuphry of Kyiv, wrote his own letter to the UN in late January.

Additionally, every parish and monastery of the Ukrainian Church is legally registered as a separate entity. Thus, a blanket ban would mean Ukraine will have 12,000+ lawsuits in European courts on its hands at a time when it is actively trying to join the EU. Last month, the UN raised concerns about religious freedom in Ukraine, in both Kyiv and Moscow-controlled areas.

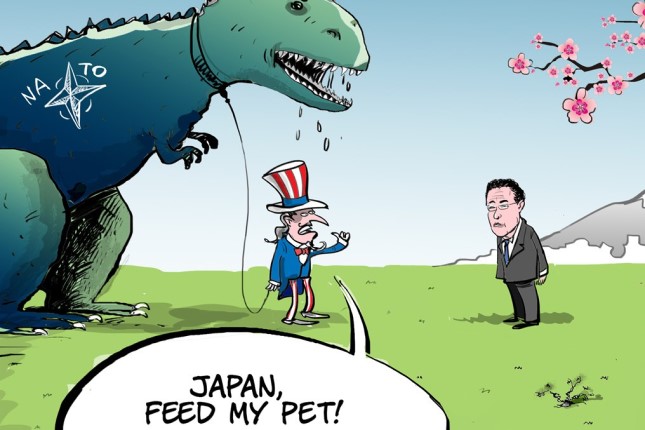

At the same time, there is no question that Kyiv has strong allies in its corner, not only when it comes to the conflict with Moscow but also in its support for the pretender church over and against the 1,000-year-old Ukrainian Orthodox Church. The American president made a surprise visit to Kyiv on February 20. Still, it was no surprise that his itinerary included a visit to the headquarters of the rival Church that the US helped create in 2018, including a photo with the head of the organization, "Metropolitan" Epiphany Dumenko.

Unsurprisingly, he showed no support for Metropolitan Onuphry, the head of the persecuted Ukrainian Church.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church, the largest religious confession in Ukraine, finds itself stuck between a rock and a hard place. While the Russian side talks of a fraternal connection between the countries and its military protection of the Ukrainian Church, the Ukrainian clergy and faithful say their voices are not heard in Russia. They largely feel abandoned by Patriarch Kirill, who was once their highest ecclesiastical authority. Every week, the Church buries more of its parishioners who died as soldiers of the Ukrainian army.

But despite the Church's evident love and support for Ukraine, the state has turned on millions of its own people, insisting that they are Russian sympathizers and enemies of the state. Exactly how far the state will go remains to be seen, but one thing is clear: the Ukrainian Church sees no allies in this religion-tinged conflict.