The New York Philharmonic Orchestra has quietly announced a complete change in the program for the May 10-12 performances at its newly renovated Geffen Hall at the city’s Lincoln Center arts complex. Russian conductor Tugan Sokhiev was originally scheduled to lead the famous Leningrad Symphony by Dmitri Shostakovich. The Leningrad has been cancelled and Sokhiev will not be on the podium. He is being replaced by James Gaffigan, in a program including a work by the Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov, along with Prokofiev’s Third Symphony and Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto.

A few months ago, the Philharmonic box office was still selling tickets for the May concerts that were clearly marked “Leningrad Symphony.” At some point this was changed, although not all ticket holders were even informed. When asked this week about the change, the orchestra’s press office first cited “artistic decisions.” A day later, it was attributed to “scheduling conflicts.” A look at Sokhiev’s upcoming concert schedule reveals, in fact, that he is scheduled to be leading the Munich Philharmonic on those dates. But clearly more than a scheduling conflict is involved.

Sokhiev was until last year the music director and principal conductor of the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, which he had led since 2014, and also the music director of the Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse in France, a post he assumed in 2008. One year ago, he was scheduled to conduct a program of music by Russian composers in New York, an appearance that was suddenly cancelled about a month after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The orchestra issued a press release explaining that, “out of regard for the current global situation,” Sokhiev would not lead the program. The decision was said to be a mutual one, but, as the WSWS pointed out at the time, Sokhiev likely had little choice in the matter. At the same time, last year’s press release announced that the Philharmonic “very much looks forward to welcoming him [Sokhiev] next season.”

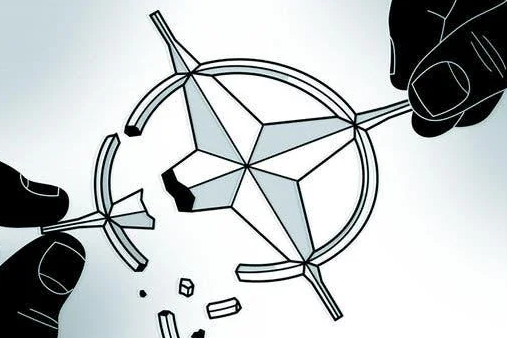

Well, next season is clearly here, and the “current global situation,” a euphemism for the US/NATO proxy war in Ukraine, is continuing, with various NATO members calling for its escalation. This is the likely reason for the “scheduling conflict” that has suddenly appeared. The WSWS last year called the cancellation of Sokhiev’s appearance “giving in to anti-Russian prejudice,” and the same applies a year later. This time the Philharmonic has not issued a press release, nor is it promising an appearance in the future. The page on the orchestra’s website devoted to Sokhiev simply states, “NO CONCERTS” both for the 2022-23 season (the second consecutive year his appearances have been cancelled) and for the 2023-24 season.

Philharmonic chief executive Deborah Borda, while denying any ban on Russian music, was quoted last year as saying there could be “no blanket decisions” about performances by Russian musicians with the orchestra. Whatever the Philharmonic officials may say, their action on the Leningrad Symphony, and their failure to announce any future date for its performance, can only be taken as a continuation and even a deepening of the broader anti-Russian propaganda campaign.

Sokhiev joins a list of others who have either been openly banned or more quietly shelved. Prominent artists like soprano Anna Netrebko, bass Ildar Abdrazakov and conductor Valery Gergiev have been blackballed. New York City’s Metropolitan Opera has led the way, banning Netrebko and Gergiev last year.

In just the last few days, word has arrived of new cancellations. Belarusian mezzo-soprano Ekaterina Semenchuk, who was announced as part of the cast of next season’s new production of Verdi’s La Forza del Destino at the Met, has been removed, according to a report on the OperaWire website. The website explains that Semenchuk recently performed several times at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, and those appearances were apparently sufficient reason for the Met to change its plans. Semenchuk, like other Russian and Belarusian performers, still has dates in Europe. Semenchuk’s schedule includes appearances with the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich and also at La Scala in Milan.

Another casualty of the anti-Russian campaign is Russian-German soprano Anastasiya Taratorkina. The Queen Sonja Competition in Norway has eliminated her because she has both German and Russian passports. She has lived in Germany for many years.

OperaWire reports on an email it received from the soprano. Quoting from a communication from the Competition, it explains, “This year’s regulations do not allow participants with Russian or Belarusian citizenship, which unfortunately means that you are disqualified even though you also have a German passport. We will of course reimburse your paid application fee and hope that the situation changes so we may welcome you to apply for the next competition.”

The more extremist among Ukrainian nationalists and their supporters have called not only for the banning of Russian performers, but also the music of Russian composers. Following a strong backlash on this issue, however, there have been US performances of Tchaikovsky, Shostakovich and others. In fact, Sokhiev himself led the Philadelphia Orchestra in February in an all-Russian program, including works by Borodin and Prokofiev, in addition to Tchaikovsky.

The New York Philharmonic has not scheduled Sokhiev, however. The Philharmonic, as we pointed out last year, may not be directly inspiring the anti-Russian campaign, but it is clearly transmitting it, and its acquiescence amounts to the same thing. The orchestra management is very likely worried about the effect that Ukrainian protests would have on its public image. When the Osnabruck Music Festival in northwest Germany performed the violin concerto of Ukrainian Silvestrov alongside the towering Eighth Symphony of Shostakovich, like the Leningrad composed during the war, the then-Ukrainian Ambassador to Germany denounced the event.

Sokhiev made a lengthy statement on Facebook last year. For the Ukrainian far right and fascistic elements, the fact that he is Russian is reason enough to oppose his work. In some circles, he could perhaps “atone” for this fact by lining up sufficiently behind the Ukrainian regime. As we reported, Sokhiev expressed dismay at having “to make a choice and choose one of my musical family over the other. I am being asked to choose one cultural tradition over the other. I am being asked to choose one artist over the other. I am being asked to choose one singer over the other. I will be soon asked to choose between Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky, Shostakovich and Beethoven, Brahms, Debussy. It is already happening in Poland, [a] European country, where Russian music is forbidden.”

The original presence of Shostakovich’s 7th Symphony on the May 10-12 programs is of special importance and undoubtedly infuriated the more frenzied advocates of the proxy war. Perhaps no work in the symphonic repertory angers Ukrainian nationalists as much. The New York Philharmonic, under its conductor Jaap van Zweden, last conducted the Leningrad Symphony in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The symphony was composed during the horrific German siege of Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), in which a million or more Soviet soldiers and civilians perished over a 28-month period that ended in January 1944. Shostakovich, who initially resisted orders to evacuate to the East for his own safety, completed the first three movements in Leningrad during the siege, which began in September 1941. The final movement was completed in Kuibyshev (now Samara), and the symphony was premiered in Moscow in March 1942. Most famously, it was performed in Leningrad during the siege, by an orchestra of 15 surviving musicians, on August 9, 1942.

The symphony was named for the city of its birth and almost immediately became a symbol of the struggles and sacrifices of the Soviet people against the Nazi invaders. Twenty-seven million soldiers and civilians died in this struggle, the largest toll for any country in the Second World War. Many millions of Soviet workers distinguished between their defense of the remaining conquests of the October 1917 Revolution, and the hated Stalin regime.

Shostakovich’s career and even his life were threatened during the years of the Stalinist Great Terror of the late 1930s. The composer came under renewed attack after the war, but during the struggle to defend the Soviet Union, he and many others found renewed strength and purpose.

Those who fought and in so many cases gave their lives included both Jews and non-Jews, Russians and Ukrainians, and many other nationalities. It is this fact of united struggle against the Nazis and their allies, particularly the Ukrainians led by the notorious Stepan Bandera, that the Ukrainian regime and its supporters would like to evade and lie about. What were the Ukrainian nationalists, Banderites and open fascists doing while the Leningraders were under siege? Many of them, and Bandera’s Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) in particular, were directly assisting the Nazis or carrying out their own pogroms and murders of Ukrainian Jews.

Source: World Socialist Web Site.