September saw a new configuration of conflicts take its final shape in a vast region stretching from China's western borders to Western Sahara. Emblematically, this was accentuated by two recent summits: the widely covered meeting of the leaders of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, and much-less-advertised talks between the leaders of the two main rival Palestinian factions, Fatah and Hamas.

The two meetings were held a few days and some 6,000 kilometres apart. They were attended by very different sets of participants and followed two distinctly dissimilar agendas. And yet, they both captured one of the key trends of the new post-global world manifested in dramatically greater independence of leading subregional countries and their intensifying rivalries.

A whole array of simmering (as yet) multi-sided conflicts is taking shape. Their course will define the future of three continents.

Between the proverbial two stools: Turkey vs Iran

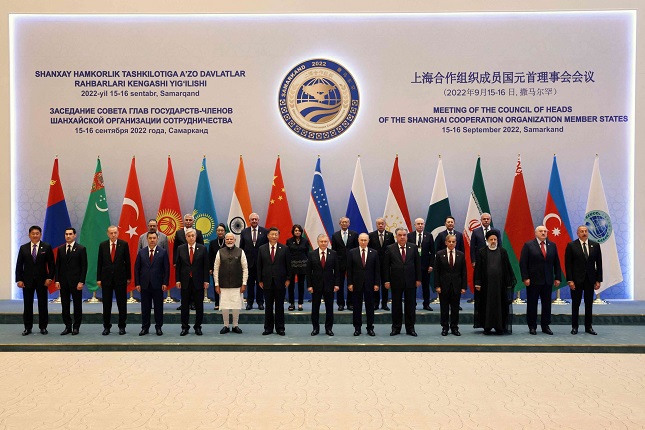

The Samarkand summit will be remembered for President Erdogan's shocking announcement of Turkey's wish to join the SCO. Turkey is a member of NATO, whereas the SCO was largely conceived of as a counterbalance to the US military and political influence in Eurasia. Erdogan's statement comes at a time when Iran, whom the US considers a pariah nation, is still going through the SCO accession process, causing quite an outcry in the West. In particular, the EU, which has been considering Turkey as a candidate for its membership since 1999, demanded that Ankara coordinate its foreign policy with Brussels. Predictably, Erdogan responded with a sarcastic remark by reminding EU officials that the European Union had kept Turkey at its gates for 52 years, yet it wants accountability.

However, despite Erdogan's upbeat attitude, his own situation and Turkey's state of affairs are both quite challenging. And it's not just a matter of having to deal with severe economic difficulties the country is facing. Turkey's attempted expansion in the Mediterranean area (Syria, Libya) has stalled. As a result, it had to switch its focus to another, less attractive region, the post-Soviet Transcaucasia and Central Asia. But here, too, it has to face stiff competition from such a tough neighbour as Iran.

September saw a flare-up of two regional conflicts: the Armenia-Azerbaijan and the Tajikistan-Kyrgyzstan standoffs. Both conflicts are unfolding against the backdrop of a regional rivalry between Turkey and Iran. Iran, for one, has issued several warnings that it would be forced to intervene if Azerbaijan's gets too carried away with its offensive.

However, Erdogan's choices are limited. Turkey's ability to play a meaningful part in shaping Libya's future has proven inadequate. Syria, too, is beginning to come out of its isolation. Frightened by Iran's growing influence and the prospects of its "breakthrough" into the Eastern Mediterranean, Arab countries are in the process of taking their first steps toward mending their relations with Damascus. Among other things, they are gradually preparing to reinstate Syria's membership in the League of Arab States. Greece is deploying its troops near the border with Turkey and, against all prior agreements, on neighbouring islands.

This significantly reduces Turkey's prospects for a forceful expansion of its political and economic influence, which explains its desire to join the SCO, where this objective could be accomplished via a subtler, negotiations-based process.

Meeting of the Council of Heads of State of the SCO Member States. Photo: AP.

A Fight for Gaddafi's legacy: Algeria vs Egypt

If anyone has any chance of asserting their influence in Libya, it is Algeria and Egypt. Although not always outwardly visible, the tensions and contradictions between these two countries are growing.

It's not just a question of their reach and the extent of their influence in Libya. Rather, it is a question of who will fill the unique niche created for Libya by Gaddafi. Specifically, this concerns the future of the African Union.

After Gaddafi's demise, it seemed for a while that Egypt could fill this niche. After all, the first 2019 Russia-Africa summit was co-chaired by Russia and Egypt.

However, following the election of Abdelmajid Tebboun as Algeria's president, his country stepped up its foreign policy activities one notch. In February 2022, Algeria, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Africa agreed to create the Group of Four (G4). The G4 nations have designated as their primary goal a greater rapprochement and closer coordination of African countries within the framework of the African Union.

The makeup of this association is far from being fortuitous. The African Union (AU) is headquartered in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The organisation itself was founded in 2002 in Durban, South Africa. It was established at the initiative of Muammar Gaddafi.

The G4 was established on the sidelines of the 6th EU-AU summit. This is quite telling, given that Gaddafi had been very keen on forging strong relations with Europe. Under Gaddafi, Libya played the role of a reliable roadblock keeping the flow of Africa's refugees from getting into the EU. Admittedly, his being on overly familiar terms with and his trust in Europe played a cruel joke on Gaddafi and ended up contributing to his demise, but that's a different story.

The founding of G4 caused real heartburn in Cairo, especially as Algeria lent its support to Ethiopia in the latter's row with Egypt over Ethiopia's Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project. Ethiopia went ahead with the project and commissioned it in February. In retaliation, Egypt backed Morocco in its standoff with Algeria over the future of Western Sahara. Morocco considers this territory its rightful possession, while Algeria has insisted on its independence.

The row over the Nile dam could spark a war between Egypt and Ethiopia, and Algeria's getting in the mix represents a highly unpleasant turn of events for Egypt.

A friend of my enemy: Israel vs Polisario

Many countries have taken to view Algeria as a significant nuisance. In a surprising twist, this includes Israel, which seems to grow increasingly peeved by Algeria's closeness with Iran. These two countries have been friendly for years, but of late, their relations have grown even closer. Some sources in the West have pointed at Algeria as Hezbollah’s backdoor in its transactions in North Africa following Morocco’s 2017 arrest, at the nudging of the US, of Kassim Tajideen, a Lebanese financier alleged to be financing Hezbollah, and his extradition to the US (he was released early in 2020).

In November 2021, Iran enthusiastically applauded Algeria's decision to vote against Israel's membership in the African Union. According to Iran’s foreign minister, Algeria had acted based on wisdom and logic, and that this measure, taken in addition to Algeria’s rational stance on Syria’s return to the Arab League, was valuable. In 2012, Iran and Algeria were the only countries to object to the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) decision to suspend Syria’s membership.

Israel retaliated by expanding its military cooperation with Morocco, including weapons contracts and a plan to set up its military base there.

Its military ties with Israel are of great importance to Morocco as its standoff with Algeria over the future of Western Sahara threatens to escalate into a full-fledged war.

Towards the end of his term as president, Donald Trump added fuel to the fire by declaring the United States’ recognition of Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara. (Notoriously, Trump did quite a lot to stoke tensions in the Near East. One such move was to recognise Jerusalem as Israel’s legitimate capital.) Since then, relations between the two countries have deteriorated even further and are growing increasingly strained. In August 2021, Algeria cut its diplomatic ties with Morocco bringing the two nations to the brink of a border conflict.

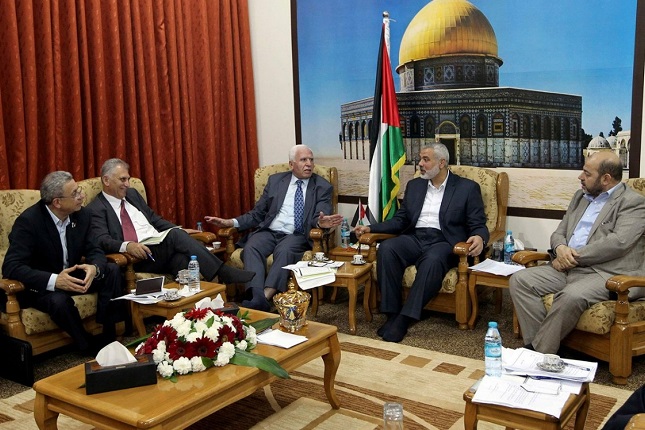

By all accounts, Israel has taken Morocco’s side in the latter’s territorial dispute with Algeria, which supports the Polisario Front, an organisation that fights for Western Sahara's independence. Algeria could not let this pass unnoticed and chose to host, in September 2022, the talks between the leaders of Hamas and Fatah, two bitterly rival Palestinian groups, held for the first time since 2016. This way, Algeria is trying to mount its counter-pressure on Israel.

Fatah and Hamas leaders decide to recognize autonomy resolution. Photo: Reuters

Life after Brexit: Britain vs France

Liz Truss, UK's new Prime Minister, made a stunning admission that she was undecided as to whether French President Macron was Britain's friend or foe. She made the statement back when she was still the UK's Foreign Secretary vying for party leadership. Macron just laughed this off.

Leaving this quibble aside, long gone are the days of the Franco-British alignment seen during the 2011 campaign against Libya and a subsequent coordinated attack against Syria. France's and Britain's attempts to boost their influence in the Mediterranean, in line with Barak Obama's policy of using others to handle crises, have failed. The UK has left the EU, and everyone is playing their own game now.

The UK, for one, is keen to expand its ties with Morocco. France, by contrast, is leaning more toward Algeria. For years, France had generally played on Morocco's side, but it had to maintain the right balance in its relations with the whole of North Africa. But the US decision to recognise Morocco's sovereignty over Western Sahara has tipped the scale and made it increasingly hard to continue maintaining the balance. Numerous signs suggest France is intent on resetting its relations with Algeria. This is at least what Moroccan media outlets have been implying when talking about the emergence of a new French-Algerian-Tunisian "axis" designed to contain Morocco. Tunisia has recalled its ambassador from Morocco as a result of the conflict over Western Sahara, while Tunisia's president hosted a high-level visit by the leader of the Polisario Front.

The serious economic challenges faced by France and the UK at the moment raise the stakes in the competition between the two countries. France needs to consolidate its clout in the EU, and the Mediterranean appears to offer the largest and most obvious resource for achieving this objective. By contrast, the UK is trying to build a new, post-European, network of alliances. The list of countries in the region with whom Britain has signed a whole range of "association agreements" is quite revealing: Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco.

Although France's chances in the race for influence in the region look better, Britain is nevertheless trying to get an advantage by trying to embed itself into the new network of alliances advanced by the United States.

Unclear prospects: from NATO to QUAD 2.0

As for the United States, its attempts to forge regional support in the new geopolitical reality have been fumbling so far. It recently announced the emergence of a new bloc, dubbed QUAD 2.0, consisting of the US, India, UAE, and Israel (not to be confused with QUAD: United States, India, Japan, and Australia).

Unlike QUAD, which was designed to mount an opposition, albeit virtual, to China, QUAD 2.0 seeks to contain Iran.

It would appear that the presence of the UAE in this "soft" alliance is just the tip of a larger iceberg. What we are dealing with here is an implicit partnership involving Israel and several Arab nations, of whom Egypt is a key country. That said, the alliance's Arab participants will have to deal with many limitations, ranging from major inter-Arab tensions over their relations with Israel and the need to present a united Islamic front over Iran to have a vested interest in good relations with China.

The partnership's obvious flaw and a sign of its fundamental weakness is its failure to include relevant Arab countries in its officially published membership list. This isn't to say, of course, that it won't take its rightful place in the patchwork of regional networks, ties, and conflicts.

QUAD 2.0 would work as at least a hint of a strong bid for influence.