The day after the U.S. government began routinely bombing faraway places, the lead editorial in The New York Times expressed some gratification.

Nearly four weeks had passed since 9/11, the newspaper noted, and America had finally stepped up its “counterattack against terrorism” by launching airstrikes on al-Qaeda training camps and Taliban military targets in Afghanistan. “It was a moment we have expected ever since September 11,” the editorial said. “The American people, despite their grief and anger, have been patient as they waited for action. Now that it has begun, they will support whatever efforts it takes to carry out this mission properly.”

As the United States continued to drop bombs in Afghanistan, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s daily briefings catapulted him into a stratosphere of national adulation. As The Washington Post’s media reporter put it: “Everyone is genuflecting before the Pentagon powerhouse… America’s new rock star.” That winter, the host of NBC’s Meet the Press, Tim Russert, told Rumsfeld: “Sixty-nine years old and you’re America’s stud.”

The televised briefings that brought such adoration included claims of deep-seated decency in what was by then already known as the Global War on Terror. “The targeting capabilities, and the care that goes into targeting, to see that the precise targets are struck, and that other targets are not struck, is as impressive as anything anyone could see,” Rumsfeld asserted. And he added, “The weapons that are being used today have a degree of precision that no one ever dreamt of.”

Whatever their degree of precision, American weapons were, in fact, killing a lot of Afghan civilians. The Project on Defense Alternatives concluded that American air strikes had killed more than 1,000 civilians during the last three months of 2001. By mid-spring 2002, The Guardian reported, “as many as 20,000 Afghans may have lost their lives as an indirect consequence of the U.S. intervention.”

Eight weeks after the intensive bombing had begun, however, Rumsfelddismissed any concerns about casualties: “We did not start this war. So understand, responsibility for every single casualty in this war, whether they’re innocent Afghans or innocent Americans, rests at the feet of al-Qaeda and the Taliban.” In the aftermath of 9/11, the process was fueling a kind of perpetual emotion machine without an off switch.

March 11, 2002: U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld

with Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Richard B. Myers and military representatives from 29 countries of the worldwide coalition on the war against terrorism at a press conference at The Pentagon. Photo: Helene C. Stikkel / DoD / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain.

Under the “war on terror” rubric, open-ended warfare was well underway — “as if terror were a state and not a technique,” as Joan Didion wrote in 2003 (two months before the U.S. invasion of Iraq). “We had seen, most importantly, the insistent use of September 11 to justify the reconception of America’s correct role in the world as one of initiating and waging virtually perpetual war.”

In a single sentence, Didion had captured the essence of a quickly calcified set of assumptions that few mainstream journalists were willing to question. Those assumptions were catnip for the lions of the military-industrial-intelligence complex. After all, the budgets at “national security” agencies (both long-standing and newly created) had begun to soar with similar vast outlays going to military contractors. Worse yet, there was no end in sight as mission creep accelerated into a dash for cash.

For the White House, the Pentagon, and Congress, the war on terror offered a political license to kill and displace people on a large scale in at least eight countries. The resulting carnage often included civilians. The dead and maimed had no names or faces that reached those who signed the orders and appropriated the funds. And as the years went by, the point seemed to be not winning that multicontinental war but continuing to wage it, a means with no plausible end. Stopping, in fact, became essentially unthinkable. No wonder Americans couldn’t be heard wondering aloud when the “war on terror” would end. It wasn’t supposed to.

U.S. Marines leaving a compound at night in Afghanistan’s Helmand province. Photo: Defense Department.

"I Mourn the Death of My Uncle…"

The first days after 9/11 foreshadowed what was to come. Media outlets kept amplifying rationales for an aggressive military response, while the traumatic events of Sept. 11 were assumed to be just cause. When the voices of shock and anguish from those who had lost loved ones endorsed going to war, the message could be moving and motivating.

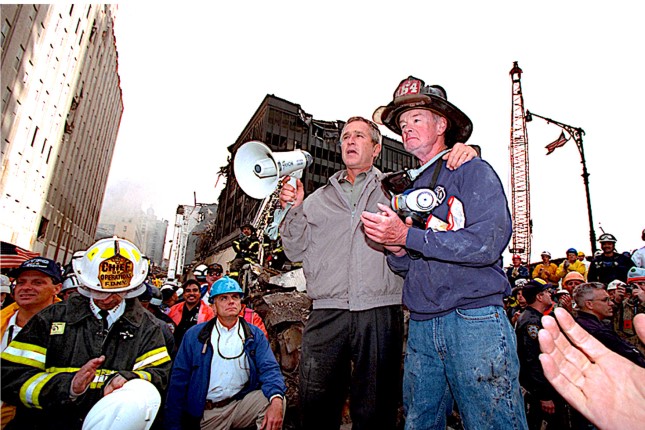

Meanwhile, President George W. Bush — with only a single congressional negative vote — fervently drove that war train, using religious symbolism to grease its wheels. On Sept. 14, declaring that “we come before God to pray for the missing and the dead, and for those who love them,” Bush delivered a speech at the Washington National Cathedral, claiming that “our responsibility to history is already clear: to answer these attacks and rid the world of evil. War has been waged against us by stealth and deceit and murder. This nation is peaceful, but fierce when stirred to anger. This conflict was begun on the timing and terms of others. It will end in a way, and at an hour, of our choosing.”

Bush cited a story exemplifying “our national character”: “Inside the World Trade Center, one man who could have saved himself stayed until the end at the side of his quadriplegic friend.”

Standing on top of a crumpled fire truck at Ground Zero with retired New York City firefighter Bob Beckwith, Bush gives an impromptu speech on Sept. 14, 2001. “I can hear you,” he said. “The rest of the world hears you. And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.” Photo: Eric Draper / George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum / U.S. National Archives.

That man was Abe Zelmanowitz. Later that month, his nephew, Matthew Lasar, responded to the president’s tribute in a prophetic way: “I mourn the death of my uncle, and I want his murderers brought to justice. But I am not making this statement to demand bloody vengeance… Afghanistan has more than a million homeless refugees. A U.S. military intervention could result in the starvation of tens of thousands of people. What I see coming are actions and policies that will cost many more innocent lives, and breed more terrorism, not less. I do not feel that my uncle’s compassionate, heroic sacrifice will be honored by what the U.S. appears poised to do.”

The president’s announced grandiose objectives were overwhelmingly backed by the media, elected officials and the bulk of the public. Typical was this pledge Bush made to a joint session of Congress six days after his sermon at the National Cathedral: “Our war on terror begins with al-Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated.”

Yet by late September, as the Pentagon’s assault plans became public knowledge, a few bereaved Americans began speaking out in opposition. Phyllis and Orlando Rodriguez, whose son Greg had died in the World Trade Center, offered this public appeal: “We read enough of the news to sense that our government is heading in the direction of violent revenge, with the prospect of sons, daughters, parents, friends in distant lands dying, suffering, and nursing further grievances against us. It is not the way to go. It will not avenge our son’s death. Not in our son’s name. Our son died a victim of an inhuman ideology. Our actions should not serve the same purpose.”

Judy Keane, who lost her husband Richard at the World Trade Center, similarly told an interviewer: “Bombing Afghanistan is just going to create more widows, more homeless, fatherless children.”

And Iraq Came Next

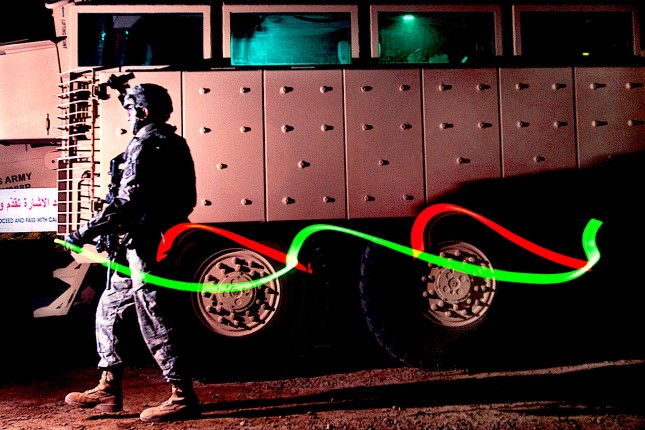

U.S. Army paratrooper with two chemical lights, Ramadi, Iraq, Oct. 26, 2009. Photo: U.S. Army / Flickr / Michael J. MacLeod.

While indescribable pain, rage and fear set the U.S. cauldron to boil, national leaders promised that their alchemy would bring unalloyed security via a global war effort. It would become unceasing, one in which the deaths and bereavement of equally innocent people, thanks to U.S. military actions, would be utterly devalued.

In tandem with Washington’s top political leaders, the fourth estate was integral to sustaining the grief-fueled adrenaline rush that made launching a global war against terrorism seem like the only decent option, with Afghanistan initially in the country’s gunsights and news outlets filled with calls for retribution.

Bush administration officials, however, didn’t encourage any focus whatsoever on U.S. petro-ally Saudi Arabia, the country from which 15 of the 19 Sept. 11 hijackers came. (None were Afghans.)

By the time the United States began its invasion of Afghanistan, 26 days after 9/11, the assault could easily appear to be a fitting response to popular demand.

Hours after the Pentagon’s missiles began to explode in that country, a Gallup poll found that “90 percent of Americans approve of the United States taking such military action, while just 5 percent are opposed, and another 5 percent are unsure.”

Such lopsided approval was a testament to how thoroughly the messaging for a “war on terror” had taken hold. It would have then been little short of heretical to predict that such retribution would cause many more innocent people to die than in the 9/11 mass murder.

A U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement helicopter passes by the Statue of Liberty as it patrols the airspace over New York City, March 2003. Photo: Gerald L. Nino / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain.

During the years to come, the foreseeable deaths of Afghan civilians would be downplayed, discounted or simply ignored as incidental “collateral damage” (a term that Time magazine defined as “meaning dead or wounded civilians who should have picked a safer neighborhood”).

What had occurred on Sept. 11 remained front and center. What began happening to Afghans that Oct. 7 would be relegated to, at most, peripheral vision. Amid the righteous grief that had swallowed up the United States, few words would have been less welcome or more relevant than these from a poem by W.H. Auden: “Those to whom evil is done / Do evil in return.”

Even then, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq was already in the Pentagon’s crosshairs. Testifying before the Senate Armed Services Committee in September 2002, Rumsfeld didn’t miss a beat when Sen. Mark Dayton questioned the need to attack Iraq, asking, “What is compelling us to now make a precipitous decision and take precipitous actions?”

Rumsfeld replied: “What’s different? What’s different is 3,000 people were killed.”

In other words, the humanity of those who died on 9/11 would loom so large that the fate of Iraqis would be rendered invisible.

In reality, Iraq had nothing to do with 9/11. Official claims about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction would similarly prove to be fabrications, part of a post-9/11 pattern of falsehoods used to justify aggression that made those who actually lived in Iraq distinctly beside the point. As I shuttled between San Francisco and Baghdad three times in the four months that preceded the March 2003 invasion, I felt I was traveling between two far-flung planets, one increasingly abuzz with debates about a coming war and the other just hoping to survive.

Secretary of State Colin Powell at the U.N.’s Security Council on Feb. 5, 2003, presenting what turned out to be false claims about Iraq’s WMD. Photo: U.S. government / Public domain / Wikimedia Commons.

When the Bush administration and the American military machine finally launched that war, it would cause the deaths of perhaps 200,000 Iraqi civilians, while “several times as many more have been killed as a reverberating effect” of that conflict, according to the meticulous estimates of the Costs of War Project at Brown University.

Unlike those killed on 9/11, the Iraqi dead were routinely off the American media radar screen, as were the psychological traumas suffered by Iraqis and the decimation of their country’s infrastructure. For U.S. soldiers and civilians on contractor payrolls, that war’s death toll would climb to 8,250, while back home, media attention to the ordeals of combat veterans and their families would turn out to be fleeting at best.

Still, for the industrial part of the military-industrial-congressional complex, the Iraq War would prove all too successful. That long conflagration gave huge boosts to profits for Pentagon contractors while, propelled by the normalization of endless war, Defense Department budgets kept spiking upward.

And Iraq’s vast oil reserves, nationalized and off-limits to Western companies before the invasion, would end up in mega-corporate hands like those of Shell, BP, Chevron and ExxonMobil.

Several years after the invasion, some prominent Americans acknowledged that the war in Iraq was largely for oil, including the former head of U.S. Central Command in Iraq, General John Abizaid, former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan and then-senator and future Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel.

The Never-Ending War on Terror

The “Tower of Light” commemorating the 9/11 attack on the Pentagon is seen behind the White House on Sept. 11, 2021, in observance of the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. Photo: White House / Katie Ricks.

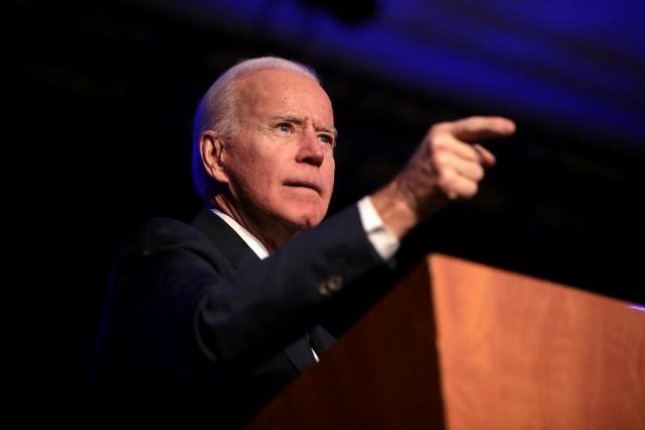

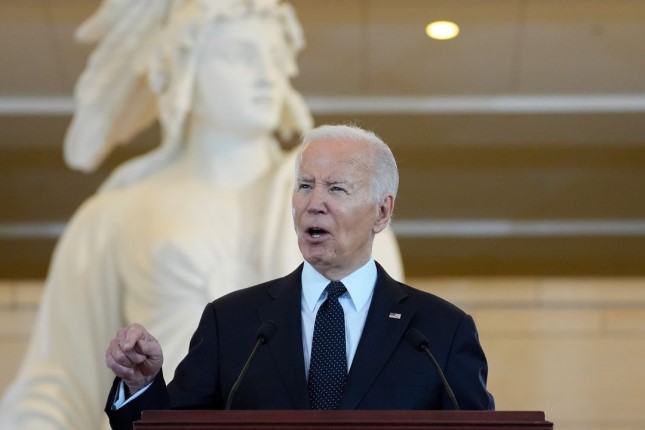

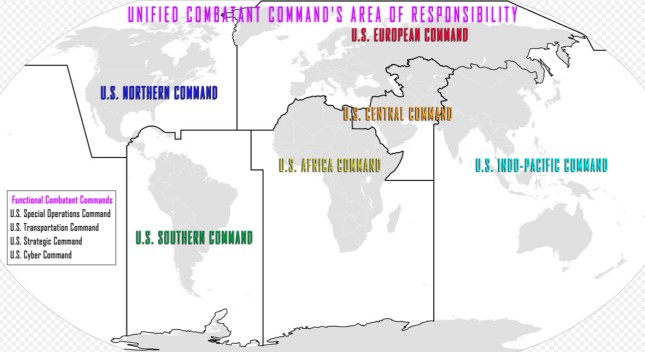

The “war on terror” spread to far corners of the globe. In September 2021, when President Joe Biden told the U.N. General Assembly, “I stand here today, for the first time in 20 years, with the United States not at war,” the Costs of War Project reported that U.S. “counterterrorism operations” were still underway in 85 countries — including “air and drone strikes” and “on-the-ground combat,” as well as “so-called ‘Section 127e’ programs in which U.S. special operations forces plan and control partner force missions, military exercises in preparation for or as part of counterterrorism missions, and operations to train and assist foreign forces.”

Many of those expansive activities have been in Africa. As early as 2014, pathbreaking journalist Nick Turse reported for TomDispatch that the U.S. military was already averaging “far more than a mission a day on the continent, conducting operations with almost every African military force, in almost every African country, while building or building up camps, compounds, and ‘contingency security locations.’”

U.S. AFRICOM area shown in yellow. Photo: DoD Updater Private / CC BY-SA 4.0 / Wikimedia Commons.

Since then, the U.S. government has expanded its often-secretive interventions on that continent. In late August, Turse wrote that “at least 15 U.S.-supported officers have been involved in 12 coups in West Africa and the greater Sahel during the war on terror.”

Despite claiming that it seeks to “promote regional security, stability, and prosperity,” the U.S. Africa Command is often focused on such destabilizing missions.

With far fewer troops on the ground in combat and more reliance on air power, the “war on terror” has evolved and diversified while rarely sparking discord in American media echo chambers or on Capitol Hill. What remains is the standard Manichean autopilot of American thought, operating in sync with the structural affinity for war that’s built into the military-industrial complex.

A pattern of regret — distinct from remorse — for the venture militarism that failed to triumph in Afghanistan and Iraq does exist, but there is little evidence that the underlying repetition-compulsion disorder has been exorcised from the country’s foreign-policy leadership or mass media, let alone its political economy. On the contrary, 22 years after 9/11, the forces that have dragged the United States into war in so many countries still retain enormous sway over foreign and military affairs. The warfare state continues to rule.

Main photo: Sept. 11, 2001: President George W. Bush making calls from Emma E. Booker Elementary School in Sarasota, Florida. White House Chief of Staff Andy Card with back to camera, also on phone © U.S. National Archives.

Source: Consortium News.