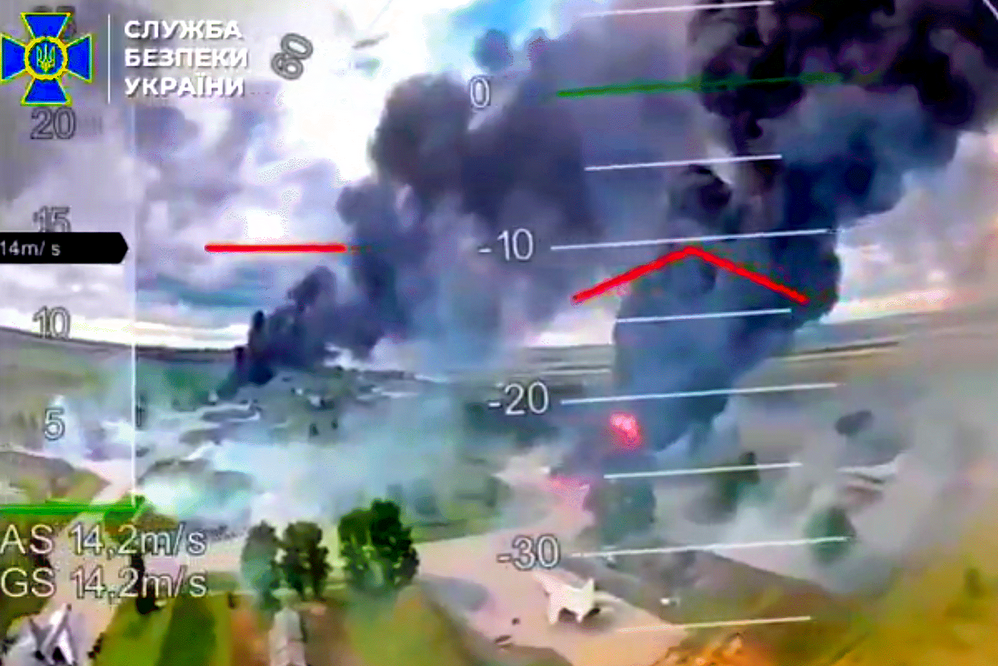

Those drone attacks on five Russian airfields last week were nothing if not daring. No final report from Moscow yet, but three figures’ worth of Ukrainian drones launched from the backs of trucks destroyed some number of strategic bombers in the Russian fleet.

Now we read all over the place — well, all over mainstream Western media — that Ukraine has “revolutionized warfare.” My favorite in this line appeared in a digital journal called The Conversation just after the June 1 attacks:

“Ukraine’s success once again demonstrates that its armed forces and intelligence services are the modern masters of battlefield innovation and operational security.”

Gasp. Splutter.

The Conversation is staffed by obscure scholars and hack-y journalists you’ve never heard of. O.K., not mainstream. But mainstream seems the aspiration, and The Conversation will get there soon enough if it continues publishing rubbish this idiotic.

It is time, certainly, to consider the implications of drone technology in the hands of powerful regimes — on and off battlefields. I mean 5,000 miles away or maybe just 50, or five, or down the block. This is the lesson of what was by any measure an extraordinary display of technological reach.

To clear our minds at the outset, the Ukrainians haven’t revolutionized anything, unless we count their success fielding a neo–Nazi military in plain sight in the third decade of the 21st century.

No, the attacks on five Russian air bases spread across five time zones were wholly beyond the capacities of the Ukraine Armed Forces and Kiev’s intelligence service, the S.B.U. And this is where we ought to begin thinking about who is doing the revolutionizing and what is being revolutionized.

There is a general consensus among analysts not bound by their ideological allegiances that Western intelligence directed the drone operation last week, so confining the debate to which service or services held the conductor’s baton. I am with Andrei Kelin, Russia’s ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, who had this to say in an interview with Sky News after the attacks:

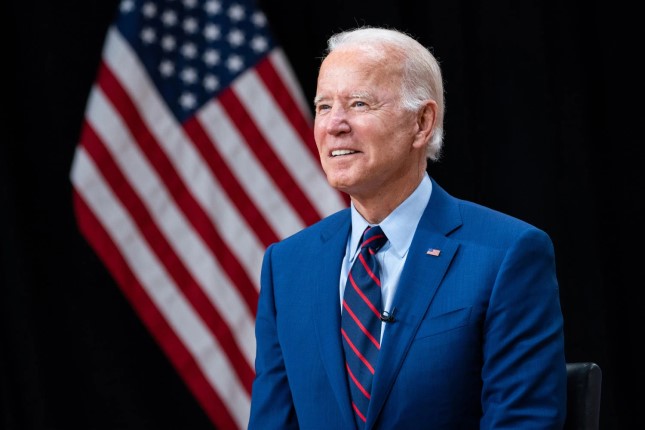

“Such a kind of attack involves, of course, provision of very high technology, so-called geospace data, which can only be done by those who have it in possession. And this is London and Washington. I don’t believe that America [was involved] — that has been denied by President Trump, definitely, but it has not been denied by London. We perfectly know how much London is involved, how deeply British forces are involved in working together with Ukraine.”

The skies over Ukraine and western Russia have been thick with the diabolic buzz of drones since the operation MI–6 evidently ran last week. Early Monday there were reports that a fleet of Ukrainian drones hit some kind of electronic-warfare facility in the Chuvashia region of Russia. A few hours later Reuters reported that Russia had launched the largest drone attack since its intervention began three years ago.

The Psychology of Drones

The use of drones is nothing new in the Ukraine conflict, of course —or in lots of others, for that matter. And if we are going to think about military applications of drones we will have to think immediately about Israel, a topic I will get to shortly.

But let us ask first what it is about drone technologies that have caused them to take so prominent a place so swiftly in the arsenals of warring states. They are efficient killers, they can be precisely controlled by remote technologists — the second lieutenant in Texas following a target in the Middle East with a stick in his or her hand —and many of the drones commonly deployed are very cheap.

Yes, yes, and yes. But we will not understand drones and the implications of their military applications until we consider what we can call the psychology of drones. This very essential question concerns risk. To an extent one could not have imagined a few decades ago, drones are intended to take the risk out of warfare for those who deploy them.

Anne Dufourmantelle, the late and acutely intelligent psychoanalyst, took up this question in In Praise of Risk (Fordham Univ. Press, 2019). It is a book I often urge people to read. Here is a brief passage pertinent to our topic:

“Zero risk — in armed or diplomatic conflicts, or even in conflicts of interest between industrialized powers — tends, in contemporary wars, to be imposed as an ethical law. It is taken for granted that no one wants to ‘risk’ losing human lives; war, from now on, should paradoxically be able to do without death….”

The intensely humanist Dufourmantelle ranged well beyond military matters in this exceptional book: She was interested in how we love, not how we kill one another.

But how well she understood “the barbarism of our ‘clean’ contemporary wars”:

“… wars whose so-called ‘collateral’ damage will henceforth entail more dead among the civilian population than the ranks of the military.”

Let us think hard about this coldly stated observation. I distinguished earlier between the use of drones on and off battlefields, far away and close by. But at the horizon these distinctions no longer hold. If drones are in some way revolutionizing instruments, they announce that wherever we are, henceforth we are in a field of battle.

Civilians Casualties

War’s first casualties in our time are civilians, to put this point another way. Following Dufourmantelle’s point to its logical conclusion, this can be said to be by design.

Has anyone made this clearer than the Israelis as they inflict their campaign of terror on the Palestinians of Gaza and the West Bank?

As +972 Magazine and Local Call, two independent Israeli publications, made plain in extensive investigative pieces last autumn, the Israeli military now uses artificial intelligence in combination with drones to track and kill Palestinians anywhere and at any time, frequently without inhibition in the innermost recesses of their private lives.

Every inch of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, as my colleague Cara Marianna reports after extended visits to the latter, is surveilled.

Here is Jonathan Cook, the estimable British commentator, in “Destroying the world as we know it,” a piece that appeared in Middle East Eye shortly after +972 and Local Call published their investigations. The Israelis had just attacked and burned alive a 19–year-old named Shaaban al–Dalou, along with his mother and two others, in a tent on the grounds of al–Aqsa Hospital, where al–Dalou was recovering from wounds the Israelis had earlier inflicted:

“It is not Hamas that is being eliminated in Gaza. It is the fundamentals of humanitarian law: the principle of ‘distinction’ between combatants and non-combatants, and the principle of ‘proportionality’ in weighing military advantage against the endangerment of civilians….

Israel is not ‘remaking the Middle East.’ It is destroying the world as we have known it for generations….

What Israel has made clear, supported by Western capitals, is that there is no safe place, not even for those recovering in a hospital bed from Israel’s earlier atrocities. There are no ‘non-combatants,’ no civilians. There are no rules. Everyone is a target….”

Easy it would be to assume that drones and totalized surveillance are “something unpleasant that happens to other people,” as Arnold Toynbee summarized English attitudes in the empire’s later decades. Let us not be so myopic as the Edwardians the noted British historian wrote of.

Let us, to put the point another way, take Jonathan Cook seriously when he observes, “Everyone is a target.”

The American Civil Liberties Union reports that roughly 1,400 to 1,500 police departments across the U.S. have drones in their inventories and routinely make use of them for, among other things, surveillance operations.

Turning the point another way, does it disturb you, even briefly, that MI–6, the C.I.A., the F.B.I. and other appendages of the national security state operate at the most sophisticated end of these technologies?

Just for a sec, I mean.

A friend forwarded me a piece the other day from The Guardian, published last week under the headline, “University of Michigan using undercover investigators to surveil student Gaza protesters.”

It turns out Michigan’s most distinguished university has been paying a Detroit security company called City Shield, nicely into seven figures, to follow students on and off campus, eavesdrop, video-record their conversations, in many cases more or less stalking them.

These are no-neck goons, not high-end drones. O.K., the University of Michigan is lower on the technology ladder than MI–6. Is there some other difference we need to think about?

Among the worst parts of this story, university administrators have used this primitively-gathered surveillance in disciplinary proceedings against some students who favor the Palestinian cause, and — not to be missed — make no apology for this operation.

“Any security measures in place are solely focused on maintaining a safe and secure campus environment,” the university said in an official statement, “and are never directed at individuals or groups based on their beliefs or affiliations.”

You get the idea. The normalization of total surveillance.

The world as we have known it, safe places as we have known them, civilians as we have known them, the University of Michigan as we have known it, the silence of the sky as we have known it, drones as we are, sadly, fated to know them.

Source: Consortium News.