Naturally this was not helped by babbling politicians waving big sticks.

Shoppers rushed ATMs to get cash for a cup of coffee. Some were unable to pay for meals they had already consumed. Here is a comment on the day.

Electronic money is the modern expression of a very old monetary fraud, “fiat money”

“Fiat money” is token currency supplied and regulated by governments and central banks. Its value relies on a government decree that it alone must be used as “legal tender” in paying for anything in that country. Its value falls as its supply increases.

Fiat money is not new—Marco Polo described its use in China over 700 years ago. Travelers and traders entering China were forced by Kublai Khan to exchange their real money (gold and silver coins and bars) for his coupons, made from mulberry bark, each numbered and stamped with the Khan’s seal. The Khan decreed that local traders were forced to accept them (“legal tender”). Foreigners got the goods, the great Khan got the bullion, and the Chinese traders got the mulberry bark (a bit like getting the rough end of a pineapple). By controlling the supply and exchange rates for mulberry money, he became fabulously wealthy, and his citizens sank into poverty.

But unlike electronic money accessed via Optus, mulberry money could not disappear in a flash.

The world has a long history of pretend money

During the American War of Independence, the colonial rebels had no organized taxing power, so they printed the Continental dollar to finance the war. As the war dragged on, they printed too many, and its fast debasement gave rise to the phrase, “Not worth a Continental.” Later, in the American war between the states, Confederate paper money used to support the army also became worthless. It was widely referred to as “shin-plaster” after its highest value arose as a bandage to wounds.

Many dictators over the years tried the fiat money trick, but so many lost their heads or their thrones that it fell into disuse, being replaced by trusted real money such as English sovereigns, Spanish doubloons, Austro-Hungarian thalers, and American gold eagles. It is mainly in wartime that people are sufficiently distracted or scared enough to allow rulers to secretly tax everyone who holds their depreciating pretend money.

Financing big wars

The last century or so has seen the explosion of big governments and big wars—race wars, class wars, world wars, regional wars, the war on want, the war on drugs, the war on inflation, the war on terrorists, the war on Covid, and now the Net Zero war on carbon fuels and grazing animals. All wars cost heaps of money, and they are so expensive that to raise the full cost from honest taxes alone would cause a revolt.

The monetary watershed was World War I, which saw governments mobilize all community resources to the war effort. Money printing plus ration cards were their main tools. Money creation destroyed currencies everywhere.

The cost of the war destroyed the German currency and the replacement Papiermark was subject to terrible inflation in 1923, which paved the way for the rise of the Nazis.

Even the mighty pound sterling was fatally weakened by wars, and the discipline of the gold/silver standard was gradually destroyed. The British gold sovereign, first minted by Henry VII in the 16th century, disappeared from circulation at the height of the Great War in 1917. The British pound became a fiat currency in 1931, and silver started to disappear from British and Australian currency in 1945 after the Second Great War. Even the mighty U.S. dollar started on the road to ruin during the Vietnam War, and gold convertibility was suspended by Richard Nixon in 1971.

We have seen the death of much of the world’s funny money in just the last 50 years. For example, in Peru, one million Intis would buy a modest home in 1985; five years later it would not buy a tube of toothpaste. Brazil had so many new banknotes they ran out of heroes to print on them.

In Vietnam in the 1980s, factories had to hire trucks to carry the bags of dongs to pay the Tet (New Year) workers’ bonuses. In 1997 in Zaire, it took a brick-sized bundle of 500,000 notes of the local currency to pay for a meal—no one bothered to count them. On the Yugoslav border in 1989, tourists foolish enough to change “hard” currency for Yugoslav dinars got 14 cubic meters of dinars. “Dinars can no longer be measured in millions or billions, but only in cubic meters.” It had become a cubic currency. These grim records were eclipsed in November 2008, when Zimbabwe suffered inflation of 98% per day.

Most governments are good at destruction—concentration camps, gulags, dictatorships, genocide, mob rule, world wars and . . . the destruction of sound money. Fiat money is their underhand method of official larceny, and few people realize that the robbery is happening until it is too late.

Future generations will look back in wonder at modern monetary madness. Words like peso, rouble, rupiah, baht, won, rouble, ringgit, inti, dinar, tolar, ostmark, dong, lira, zloty, cordoba, sole, cruzeiro, and yuan will join “shin-plaster” as descriptions of worthlessness. Most world currencies are on the same slide to oblivion—the Australian dollar has lost over 90% of its purchasing power in the last 70 years.

“You can’t print gold or store it in computers"

Real money is always measurable by weight, such as pounds, grams, pennyweight, ounces of gold and silver, or carats of gemstones. It cannot be counterfeited or corrupted easily.

But fiat money relies for its value on the honesty and openness of the rulers. Even a monetary fool such as Fidel Castro could see what caused Cuba’s inflation. In 1993 he stood up at a rally and declared: “There are nine billion too many pesos in Cuba.”

Last week’s Optus money crisis in Australia is a harbinger of the future.

While clinging to cash is a good start to avoid inevitable technological catastrophes like the Optus crash it’s not enough. The war on cash is really just the next step in what’s really a war on the prosperity of the people, and as the globalist left ramps up the assault—plans to abolish cash come with “Net Zero” and “pandemic preparedness”—we must fight to restore sound monetary systems. Going along with the abolition of cash means a future like this: “Sorry you have had your sausage for November; would you like a green smoothie with crickets and soy instead?”

The Optus shock warns us that electronic money will join Mulberry money, Shin Plaster, and cubic currency in the long history of failed political money—how much better a system where we can engage in commerce without a far-off fiat dictatorship?

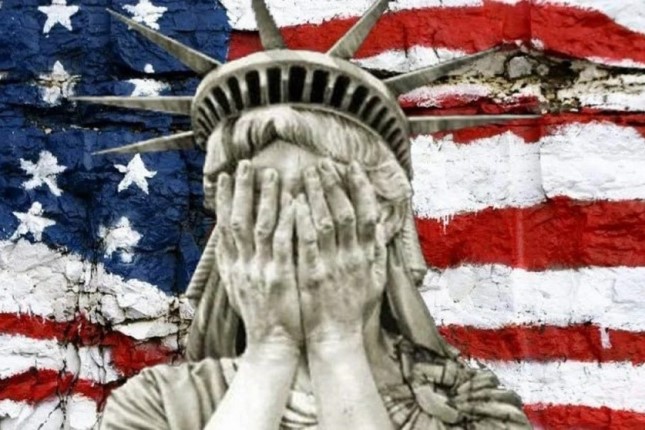

Photo: Cartoon provided courtesy of the author.

Source: American Thinker.