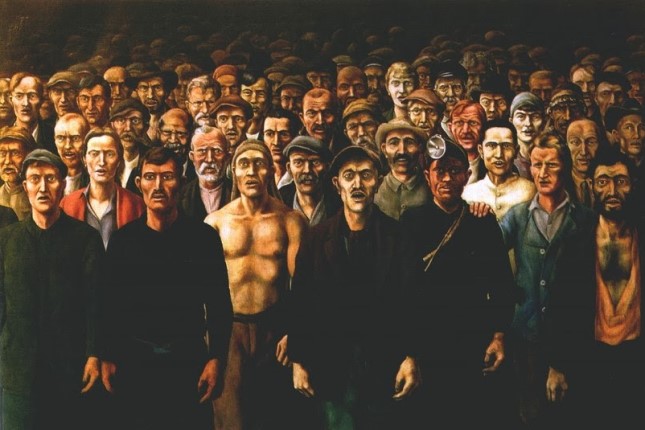

With the advent of industrial capitalism in the 19th century, it was typical for factory workers to have six work days a week and up to 16 working hours per day. This atrocity understandably urged the working class to resist such exploitation vigorously, made communism a popular idea and placed Karl Marx on the podium of the greatest intellectuals of his century. Revolution in Russia was particularly scary for greedy capitalists in Europe, and they had indeed to limit their appetites.

Henry Ford became one of the first employers to adopt a five-day, 40-hour week at his Ford Motor Company plants in 1926. But this was not just a response to pressure from the labour movement. By that time there already some awareness began to grow that mass production requires mass consumption as well, and comfortable employment is the main way to grow the middle class – the customer base for all kinds of products and services. The 8-8-8-time management formula emerged: eight hours for work, eight for family and consumption, and eight for sleep.

But in fact, if we look at it closely, there hasn't been much improvement in labour conditions for almost a hundred years. Economic development caused growth in the level of consumption, not decrease in the number of working hours that we have. If you are a happy representative of a middle class in a developed country, it is most probable that you, unlike your grand-grand-parents in the 1920s, enjoy a private car, travel abroad at least twice a year, and often have a second residence somewhere in the countryside by the lake. But you work hard for all that. And most probably you work more than 40 hours a week. In fact, much more.

Labour productivity has been growing dramatically – with all the new waves of automation, robotization, digitalization and so on. And now we are finding ourselves in an interesting situation. We are debating on the impact of AI, that threatens to take away work from millions of people, and presumably send away lots of us into a forced leisure paradise (or employment centres, of course).

And at the same time, most people experience high-stress levels, permanent burnouts, and resent imbalance between work and personal life. Everything that led to an ongoing global trend of "The Great Resignation", as dissatisfied employees are voluntarily resigning from their jobs en masse − the trend that began in early 2021 in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and only gaining steam since then.

Pradoxically, many of them feel same as participants of the Haymarket riot in Chicago in 1886, when workers demanded an eight-hour workday, singing: "We want to feel the sunshine, and we want to smell the flowers. We are sure that God has willed it, and we mean to have eight hours." However, nowadays the struggle is not for the eight hours and five days workweek, but for alternatives to it.

A six-hour workday or a four-day workweek

John Maynard Keynes, one of the most prominent economists of the 20th century once predicted in the 1930s, that people can make a 15-hour workweek in a few generations. While US President Richard Nixon, echoed him, stating somewhat around 70 years ago that we would have to work four days "in the not-too-distant future." However, for most of us this future hasn't yet come.

Proponents of a shorter workweek argue that reducing the number of working days (or at least hours during the five-day workweek option) while maintaining productivity levels can result in increased job satisfaction, enhanced mental health, and greater overall happiness. And quite possible that now is the right moment for a new wave of democratization of labour law and at least some transformative changes in the working schedule in favour of rest and well-being.

The redesigning of working conditions to four-day or six-hour options has only recently begun. The EU is experimenting with the alternatives most, but waves seem to be sweeping across Australia and Japan as well. Let's have a look at the experience of various countries with it.

Sweden and other EU countries

The first country that widely and officially tried shortening working hours and pulled the idea across Europe was Sweden in 2015. Within a two-year pilot project involving a range of various employers, including entrepreneurial fields and start-ups or nursing homes, it came out that a form of 6-hour work day doesn't fit all of these fields and adds expenses in some cases for the employer but also leads to excellent results of productivity.

For example, an experience of nurses working for Svartedalen's elderly care home in Gothenburg showed this opposition: they were taking fewer sick leaves, and the quality of their work became higher and more creative. Workers felt happier and better than before. This six-hour experiment led to hiring more employees because someone had to be always there for the old folks. At the same time, the experiment showed that shortened working days aren't a good solution for aspiring entrepreneurs, who need more time to develop their businesses.

Japan

An interesting example outside the EU is Japan, known for its intensive and excessive work culture. The country is now slowly moving towards a 4-day workweek, which seems to be a radical change. Japan is the home of the so-called karōshi effect, death from work. This phenomenon spread due to the aftermath of World War II and the debt Japan had to pay, and was especially widely-spread in the 70s − 90s. People were dying due to heart attacks or suicide at the young age of 20 to 40. Even 60 hours a week is proving devastating to health.

But since then work culture in Japan has changed. Polls among the urban population show that people work mostly 30 to 40 hours a week. It was made possible in 2019 when a labour reform was passed at the national level limiting the rights of employers, which ended their abuse.

It was Microsoft Japan that tested a four-day workweek and revealed the data proving that the company's productivity increased by 40%. So, today, around 9% of businesses shifted to this model, but unlike Microsoft, most of them cut the salary up to 20% off.